Sure, he's got a famous boss - and one who's a terror on the drumkit himself. But the Foo Fighters drummer says his real allegiance is to rocking honestly and with style. And there's no better proof of his aesthetic than the Foos latest and greatest blockbuster of an album Wasting Light.

In 1979, when Taylor Hawkins was eight years old, two of the biggest albums on the charts were the Police's Reggatta de Blanc and Pink Floyd's The Wall. Hawkins took notes. When not surfing at Laguna Beach or riding his banana bike, young Taylor was fascinated by the AM-dial fare he'd hear on his mom's car radio. Soon the Eagles' "Hotel California," Queen's "Fat Bottomed Girls," and Kansas's "Carry On Wayward Son" awakened his nascent rhythmic sensibilities. Later, when he got his first turntable, he wore out the grooves of Captain Beyond's Down Explosion.

Fast-forward some thirty years, and Taylor Hawkins plays drums for one of the biggest rock bands in the world, enjoys a freewheeling side project that enables his love of all things 1970s, and, by his own account, is getting paid more than adequately for his efforts.

A consistently humble and self-effacing musician, Hawkins also has the unusual honor of playing drums behind Dave Grohl, one of the greatest rock drummers of his generation. But as a sincere and hardworking player and all around good guy, Hawkins sees opportunity where some might see trouble. His optimism, talent, and self-awareness make him not only an essential ingredient to the Foo Fighters' success but also a great role model for any drummer intent on understanding the meaning of the term team player.

On such Foo Fighters albums as There Is Nothing Left to Lose, Skin and Bones. and One by One, Hawkins plays burly rhythms in step with Grohl's guitar. The drummer's own project. Taylor Hawkins & the Coattail Riders, finds the

quintessential Californian singing, writing, and playing guitar, bass, and drums on diverse material that recalls everything from Queen and the Eagles to Mahavishnu Orchestra and Rush. Can't escape the '70s!

The Foo Fighters' latest album. Wasting Light, which also includes Pat Smear and Chris Shiflett on guitar and Nate Mendel on bass, blasts a return to the past even more emphatically, taking shape in an all-analog process that required Hawkins to perform nearly perfect drum tracks live to tape. Grohl and producer Butch Vig didn't let the band within fifty miles of a computer, so Taylor had to bring his "A" game. And that's just the way he likes it. His drumming on such fantastic Foo flamers as "Rope," "Dear Rosemary," and "A Matter of Time" reveals his tight working relationship with Grohl, as well as his own remarkable consistency, signature time feel, and searing hand and foot patterns.

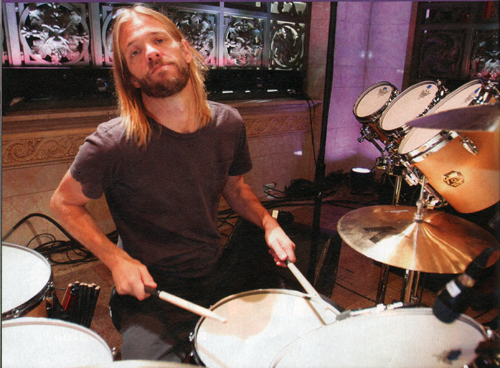

Taylor Hawkins is nothing if not physical. He's a visual beast of a showman, as any Foo Fighters video attests. Long-limbed and rangy, like a rubber-band man with a blond mane, Hawkins attacks the kit with speed and power, but also with grace and textural nuance. Some listeners may not be able to tell the difference between Grohl's elephantine pummel and Hawkins' lithely propulsive groove and speed-demon fills, but much of the Foos' magic lies in the duo's twin yet separate identities. Best friends enamored of each other's skills, Grohl and Hawkins lay the foundation for every Foo Fighters song. Hawkins, though, is not (as some claim) "the second-best drummer in the Foo Fighters," he's simply the only drummer for the job.

MD: There's a marked 70s influence in your playing. You use three concert toms. The name of the 70s cult band Captain Beyond was stamped on one of your old bass drum heads. Your drum tech, Yeti Ward, says you chose a natural wood finish because Don Henley used it in the 70s. Are you just a child of the era?

Taylor: Remember Closet Classics on MTV? They used to run videos for the Eagles' "I Can't Tell You Why" and "Heartache Tonight." They're in the studio and I lenley lias these light wood-finish Ludwig drums. I always thought they were cool looking. And Phil Collins had some natural drums for a while too.

MD: Your harmony vocals on the Coattail Riders' "Not Bad Luck" sound exactly like Queen. "James Gang" is another Coattail Riders song.

Taylor: So what the hell is this thing! flaughsl I don't know. That was my first love, 70s music...a lot of AM radio that I listened to in the back of my mom's car. Also, the harder rock my brother would listen to before be got into Kansas and Led Zeppelin—all those 70s FM rock staples.

MD: You wear the 70s like a badge at times.

Taylor: It's just part of my aesthetic. It's what I love. We have a TV room in our house, and I have it decorated my way: It's got one of those round egg chairs with the internal speakers, and a leopard-print shag carpet. The room's painted red, with old rock photos everywhere. That room looks like me.

If pressed to analyse it, I'd say the 70s is my comfort zone. This is the music thai makes me comfortable. At the same time, I don't see the Foo Fighters that way at all. We all grew up on rock 'n' roll. But my influences don't stop there. In the 90s I loved Jane's Addiction; that was super-duper important, as was Soundgarden. But in the 70s drummers had their own personalities. The way music was recorded then, there was no chance to get rid of that personality, unless it was all session musicians. The rough edges of each musician are what gives them personality Charlie Watts lifting his stick up every

time he hits a backbeat on the snare, Roger Taylor cracking open his hi-hat every time he hits the snare, Bonham having a real laid-back feel, or Stewart Copeland being on top....

MD: Or Don Henley's feel, though he is underrated as a drummer.

Taylor: He's a great drummer. I was bummed when I heard their last record, because they used the dude that plays drums for them live — who is probably technically a better drummer. But Don Henley has a sound, that '70s bar-band groove.

Taylor's Roadside Records Let's Get Physical Hawkins/Grohl Mind Meld Whip It Good Solo Sticking Practicing Here and Now Second Best?

MD: Dave Grohl said in Electronic Musician that he hates what producers have done to drummers since the '90s.

Taylor: I agree. Part of our reason for recording Wasting Light to tape was about taking the power back. The last couple of records we made, people were taking files home to manipulate. How can producers not do that if they have the ability? All they want to do is make a perfect record. That's become the norm. But it's to the detriment of what I consider to be honest, real rock 'n' roll.

If it's a Nine Inch Nails record, great. One of my favorite songs is "I Feel Love" by Donna Summer, and that's an early drum machine — totally weird sounding and awesome. But don't record a drummer and then turn him into a drum machine and grid him and make every hit perfect. Just use a drum machine — be honest. If I make a record and the producer wants to do that, I

might as well hit each drum and each cymbal and say, "There's my samples, now make it what you want." Our engineer sometimes records new bands at [the Foo Fighters' L.A. studio] 606, and he says the drummers want you to grid their drums. They think that's the way it should be.

MD: I heard that even Butch Vig was taken aback at the idea of recording Wasting Light without a grid or Pro Tools.

Taylor: Sure, Butch is a perfectionist, and he's been making records that way for fifteen years. If you want to be a perfectionist when we're recording to tape, fine, bust my balls all day long. I'll work all day — let's get it as perfect as I can get it. But the process didn't change much this time, even though we went all analog. What changes is the process after I'm done—there is no process after I'm done! The drums are what they are.

Before, especially the record we did with Gil Norton [Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace], I finished recording drums, and I don't know what happened after that. They might say, "Oh, we barely touched them." Do I believe that? There's a lot of trickery going on.

MD: On "I Should Have Known" from Wasting Light, you can really tell that the volume is peaking the meters. It's dramatic.

Taylor: That comes down to the mix as well. It was mixed by hand, no automation, no flying faders. Dave was in charge of my drums when they mixed. He'd come in after every mix, saying, "Dude, the meters are pinned!" I loved it. I'll never make another record with computers. I want to do it analog forever.

Sure, you have to play tight, but that's relative. How tight were the White Stripes? Meg is not a perfect drummer. I like that her drumming is loose. It's good for people's ears. Everyone was so programmed into thinking every recording has to be perfect. Then Jack White comes along and says, "No, everything doesn't need to be perfect." So what if she speeds up and slows down and screws up a fill here and there? Heaven forbid! Listen to Stones records, man.

MD: Recording all analog is great for those who can afford it.

MD: But Wasting Light was recorded to a click?

Taylor: Yes, and we did a little bit of tempo mapping, by hand. Butch would sit there with an Alesis drum machine and tap it, bump it up a few notches here and there. My time is not perfect in the studio. For us to be able to edit between takes, it was a lot easier if we cut the drums to a click track. But at first I was the one who said the whole tape process was taking too long. We did a lot of actual razor editing of tape on the first few songs, and I said, "Why don't we just punch in?" Nothing Left to Lose was all punching. Big deal.

MD: How do you play with such physicality yet maintain control?

Taylor: I don't know, it's just how I taught myself to play. I always played

too hard as a kid. Band teachers would tell me, "You're playing too hard." They threw me out of jazz band in high school. Again, "You're too loud, too fast." It's not a thought process, like, / have to hit harder. I wish I didn't sometimes! I would probably have more control if I was more controlled. I do work on it. A friend of mine is a jazz pocket drummer, then he joined a rock band. He asked me, "How do I play harder?" I couldn't answer that — it's just how I play.

MD: But how do you play high off the kit, and with speed? How did you build your speed?

Taylor: I have no rudimental training. My rudimental training was Rush's Exit Stage Left and the Police's Zenyatta Mondatta. I emulated my heroes. I played along with those records. That's how I learned. Ghost in the Machine and Zenyatta, those were my two Police bibles. Copeland is definitely one of my major heroes.

Queen's Live Killers was another major influence, though I don't play anything like Roger Taylor, who's a really melodic, musical drummer. He's got a great voice, and he's a great songwriter. I always looked at him as being more than a drummer. He was always a presence behind the drums. He was never a crazy hard hitter with long extended solos. But he always had a lot of personality behind the drums. Whether he was choking a cymbal or doing flourishes on his Rototoms, he played the right thing for the song. He

did almost all of Queen's background vocals. He had the highest voice. A drummer with great feeling—a super-big rock feel and great time.

MD: And you're a fan of Don Henley for similar reasons?

Taylor: Yes. They are similar drummers in a way. Very much for the song, great singers, their sound was very important. Roger Taylor had personality. There's a version of "Spread Your Wings" on Live Killers that's one of my all-time favorite drum tracks. It's so pocket and so perfect. Great long fills around the world. Another album I played along to as a kid was Genesis's Seconds Out. I still don't have those kinds of chops — though I can fake it!

MD: Fake it? Your drumming on "Louise," from Taylor Hawkins & the Coattail Riders, is no faking.

Taylor: That is a total lift from Phil Collins: "Wot Gorilla?" off Genesis's Wind & Wuthering. It's a different time signature—the Genesis song is in 4/4 and "Louise" is in 6/4—but it's the same feel. At the time of the first Coattail Riders record I was really into Phil Collins.

MD: You're a natural player.

Taylor: Drums were easy for me from the start. A friend showed me the basic rock beat, and I could play it right away. As far as playing with passion or physicality, I can't really give any tips. I wouldn't know how to explain it. Dave can't explain the way he plays drums. He had a lot of influences — he liked Cameo, that funk drumming. The beginning fill of "Smells Like Teen Spirit," that's kind of a Cameo thing. Those are just little things you pick up along the way that naturally appeal to you, but you don't know why.

MD: Your drum fills in "Rope" are almost quintessential 70s.

Taylor: We tried a bunch of different things. I had other things in mind that weren't working out. I worked on that section for an hour and a half. That's too much time for Dave! [laughs]

MD: What about the fill at the beginning of "Dear Rosemary"?

Taylor: Originally when we did the demo I played something else. The fill was half as long as it ended up being. But one of Butch's favorite rock drummers is Ian Paice. Once Butch discovered that I could do buzz rolls into rock fills, which Ian Paice is famous for on Deep Purple songs like "Burn" and "Highway Star" and "Space Truckin'," he wanted me to do buzz rolls all over the place. I do them in "Rope" after the choruses. That opening fill in "Rosemary" is also like Phil Collins on "Paperlate." That has buzz rolls with toms interspersed. It's all Motown.

MD: The Foo Fighters' recording approach begins with you and Dave laying down the basic rhythm track, right?

Taylor: Yes. I think the reason Dave anc I tend to start the tracks together is because we're both drummers. As well as being an amazing rhythm guitar player and pop/rock songwriter, Dave identifies as much with drums as anything, if not more than anything. He can get his ideas down holding a guitar and communicating with me as the drummer, and that creates the foundation of the song. Dave can say anything. He'll say, "Play a Motown beat," for example, and we can communicate really well that way. It helps him to be able to work out the arrangement in his head. It's almost like I'm his drum machine.

MD: Are you aiming to lock in with his guitar?

Taylor: Yes, Dave is very into the rhythm of the riffs being locked with the drums. That isn't always the case with rock music. Often the drummer will be playing something simple. Coattail Riders is much more free, with more over-the-bar moments. But with the Foos, Dave likes the drums and the guitar riff to be very locked.

MD: How does the creative process start?

Taylor: Dave will come in with an idea for a guitar riff. He'll have a chord sequence or a melody, and he'll sing me the chorus or an idea for the verses. I'll try different rhythms or ideas with his ideas. Straight time? Half time? Then we'll work out the arrangement and the feel of the song that way. And then we'll record a rough demo — all done very quickly, maybe half an hour. Dave is so quick at laying down a bass track and a couple rhythm guitars. They're very raw and simple demos, but they give him a blueprint for how a song should sound. Then he takes those files or tapes home and works out the melody and what the arrangement should be. Then we work on arrangements together.

MD: The two of you do all that before the rest of the band comes in?

Taylor: We do the groundwork, then the other guys come in and throw in little bits and bobs. Nate floats around like [the Who's] John Entwistle — he's very melodic—where Dave's rhythm guitar is almost more of a bass track. Again, like a Who thing almost. The sound of the Foo Fighters is almost the sound of me and Dave locking in, then Nate playing over the top of it.

MD: You're a long-limbed, wiry guy, so perhaps people don't realize how hard you hit. Do you think of your arms as whips?

Taylor: I don't think about these things—but I gotta think about it for Modern Drummerl [laughs] It's just my own weird self-taught way of playing drums. A big influence on me was Steve Perkins. I remember watching him with Jane's Addiction.. .his big Afro. He was like an animal behind the drums. Not as hard-hitting as I thought he was—he's got a lighter touch than I do. He reminds me of Gene Krupa. He's got a bouncy feel. He's really creative.

I am so lucky — just after high school I had Steve Perkins, Matt Cameron, Dave Grohl, and Jimmy Chamberlin. These amazing stylistic drummers who had their own thing and were so awesome and so creative and had so much feel. Nowadays with the advent of Pro Tools, you don't get as much of that. There's a couple guys I like. Ronnie Vannucci from the Killers is one of my favorites. He's like Bun E. Carlos. And I like Fab Moretti from the Strokes. Those are my two favorite drummers right now.

MD: You play so loose and fast. Is your grip similar to the Moeller technique or more of a tight fulcrum?

Taylor: I hold the sticks more loosely. I try to take advantage of rebound. In the past I did more of a downward stroke, but overall I think you get a better sound if you use more of the rebound. I watch Kenny Aronoff, who uses a lot of rebound, and he can do whatever he wants.

MD: Like Aronoff, you have a readily identifiable snare drum crack. Where do you hit the snare?

Taylor: Right in the middle. I get a rimshot pretty much every time. I kind of turn my snare drum up toward the set a little bit, like a jazz guy. I aim it in a little bit so that I can make sure to get a good rimshot. I don't like the snare too low. I sit at about medium height. The snare is a little high. I think I get a whip like motion on the snare drum. My drum tech, Yeti, says I play hard. He is way bigger than me, but he says, "I don have that whip like you do." They always tell him to play harder when he' soundchecking my drums, to simulate my playing. But I don't know where tha whip came from. It's just natural. I am so natural! [laughs]

MD: Can you break down what you're playing in the YouTube video titled "Taylor Hawkins Drum Solo"? You incorporate the concert toms and play a lot of interesting patterns around the kit over a straight-four bass drum.

Taylor: [Watching video] Okay, this is from a Foo Fighters gig. The first part of that solo is directly ripped off from "Dance on a Volcano" from Genesis's A Trick of the Tail. And then there are some little high torn things...then the floor-tom-to-Rototom part that's directly from the drum solo on Queen's "Keep Yourself Alive" from Live Killers. Roger's playing five over four there. It's all my version, completely different, but my interpretation. Then I stop and do a section from Rush's Exit Stage Left "YYZ" drum solo. Neil Peart calls it the "schizophrenic" section. He stops and hits weird things. Then I start playing triplets and crossover triplets between the snare and the floor torn. Not sure where that came from. Maybe a Buddy Rich idea. All of those things are directly ripped off from my three favorite solos as a kid.

MD: On "It's Over" from Red Light Fever, the intro drumming sounds like a faster version of John Bonham on "Good Times Bad Times." You play great unison drum fills with the guitar, then the outro is almost like a prog rock arrangement.

Taylor: I wrote that on the piano almost as a Bee Gees/Beatles melodic thing. Very light and pretty. When I write music, it tends to be pretty simple. But I like to mess songs up. One of the guys who helps me make these records is my friend [and Foo Fighters percussionist] Drew Hester. He always gets frustrated with me because he thinks my songs could be hits if I didn't mess with them so much! Projects like Coattail Riders are my outlet for everything I want to do outside of what I normally do in the Foo Fighters. The little prog intro in that song and all the weird stabs and the Mahavishnu outro, it's the bookends to this really simple, Beatles-ish pop song. I was having fun with arrangement.

MD: "A Matter of Time" from Wasting Light also has a rhythmic turnaround of sorts.

Taylor: In the middle, that's where the rhythm sort of falls over the bar. Dave came up with that. Again, it's Dave bucking what would normally be just a driving rock song. Just due to the fact that Dave is a drummer, a lot of what he writes is rhythmically interesting. The melodies are always there, and there's always a strong chorus. Dave is such a great chorus writer. So it's great to shove all this other weird shit around it. When Dave and I get together, we're just musos. We love to push ourselves musically and impress each other — and impress ourselves. There's a drummer's spirit to this band, no question.

MD: What do you practice these days?

Taylor: Practicing is usually done with the band; that's how I like to practice. Many drummers will say, "Oh, no wonder you suck," but I don't really find it that pleasing to just sit around and play drums. But if I do, I'll sit with a click track and see how long I can play time, both fast and slow. I practice really slow 2 and 4.1 wish I'd had a good drum teacher when I was ten, who would have told me that just learning "YYZ" all day is not going to be enough, that I should play time with a click. If my younger self had had the foresight to play simple open time at 80 bpm for an hour even day, that would have been very helpful. So when I sit down to practice now, that's one of the things I like to do.

I find that I don't really need to be any faster. As far as chops are concerned, I feel you get all your chops within the first five or ten years of learning how to play drums. That's where the sharpest learning curve happens. Your muscle memory is just coming into shape, and then after that it's all about refining things. If I hear a lick from Mahavishnu Orchestra and I want to be able to play it, I will try to master that lick for an hour. Of course, I never will master it.

If there's anything I'd like to refine, it's my sense of time. At the end of the day, that's the most important thing. For young drummers, sure, spend a couple hours learning your crazy jazzy licks, but also practice playing straight time, preferably slowly. Because the more space between the notes, the harder it is to keep really good time. Playing slow is a lot harder than playing fast. Doing it well and making it feel good, that's the challenge. That's why Jeff Porcaro was so great. And Charlie Watts and Ringo and Alan White. That drumming is so great because of the space between the notes. That's harder than anything. Some guys are just better at it than others.

MD: How do you warm up before a show?

Taylor: I just have a pair of drumsticks in my hands for a half hour before we get on stage. On whatever couch or pillow is available, I do single-stroke rolls, maybe paradiddles. Nothing strict. The chorus beat in "Rope" is a paradiddle, directly lifted from Neil Peart. It's "The Spirit of Radio" all the way. When we were doing the demo for "Rope," everyone thought it was my idea. But I have to say to Neil Peart in Modern Drummer. I'm sorry I stole that from you, Neil, but it was Dave's idea to do that, not mine! [laughs]

MD: How does it feel to play drums in a band led by one of the most famous drummers in the world? Some people still think Dave Grohl is playing the drums on Foo Fighters records.

Taylor: If you've got ears you can hear that Dave and I are totally different drummers. And the fact that we're both drummers is a big part of the chemistry of the band. It's me and Dave communicating on stage and in the studio as drummers. I am honored to be the drummer for one of the greatest rock 'n' roll drummers of all time. But at the same time, it's been important to find my own space within this band and be my own drummer. Dave is super-sensitive to that. He may know rhythmically what he wants to hear, he may want a specific beat, but it's like that with any songwriter, even if you're not a drummer. And I'm down with that — I want what Dave is hearing in his head to come to fruition. And if I can influence it in a good way, make a change that makes the song better, that's great.

Yeah, I'm always going to be considered the second-best drummer in the Foo Fighters. That's something I've gotten comfortable with, because I have to be comfortable with it. But I have the best job in the world. And the truth is, Dave is my best friend. So we're okay. It's everybody else who says, "Oh, you're not as good as Dave."

Some people say we're just two different kinds of drummers but we're similar enough to work together well. That really is the case. I can do what Dave wants for his music. You can't compete with Dave Grohl on any level. He's a supernova, a great musician. He's a tsunami in everything. He's a great frontman, and he's the nicest guy. If there's a rule book on the best way to be a popular rock musician — I hate the term rock star — it's Dave. He does it right. He doesn't have a huge ego, though he's got confidence for days. He doesn't take himself seriously, but he takes the music seriously. From the moment I was in his band I thought, Be like this guy.

I've also learned everything I know about recording drums from Dave. So basically I have one of the greatest teachers in the world. As musicians, we're all searching to be the best we can be. I have the best role model in the world, who I see every day. We're not competitive.

The outside view? Whatever. It is what it is. Sometimes I've had to develop a thick skin about it. But I am so blessed and so lucky. I'm in this huge rock band. I make way more money than I ever should make doing what I do. And I get to be in a band with my best friend. It's all good.