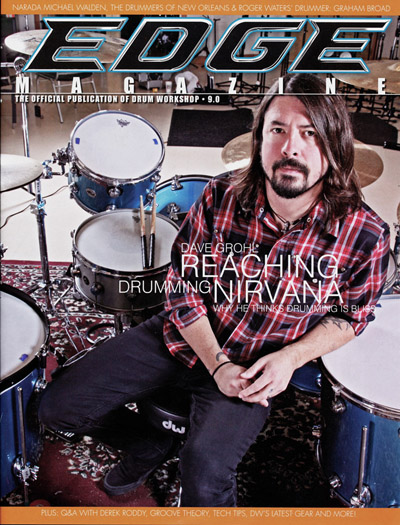

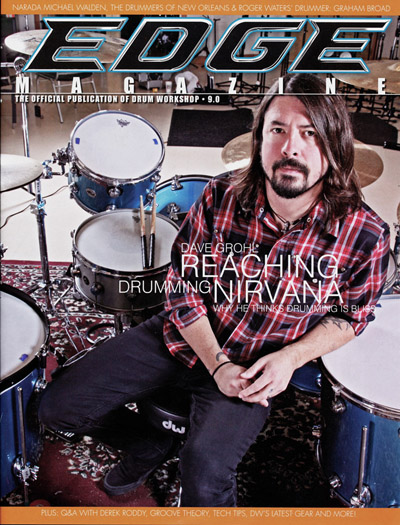

Reaching Drumming Nirvana

Edge

Dave Grohl is a drumming icon. His work with Nirvana is timeless

and his so-called ďcomebackĒ with Them Crooked Vultures has

paired him with Zeppelinís John Paul Jones, creating a rhythm

section for the ages. we asked Angels and Airwaves stickman,

Atom Willard, if he would chat with his good buddy and he kindly

agreed. we love when two drummers get together to geek-out,

especially when itís these guys.

Iíve known Dave

Grohl for over 15

years. In that time,

heís taken my bands

on tour; heís had me

and my girl over

for dinner parties,

costume parties,

birthday parties,

and drinking

parties. Heís even

sung me happy birthday, but heís never EVER told

me he loves disco drumming, and thatís how this

conversation began. I donít really want to call it an

interview, because itís more of a mission statement

to me: how to make rock and roll do just that. Dave

talking about music and drumming, and doing it

the way he always does, with humility and humor,

and itís more of an honor to be a part of that than

than anything else. To hear Dave tell a story is to be

there, and sometimes itís just about friends or his

kids, but no matter what, you find yourself smiling

the whole time. I hope you can feel the energy that

was in the room. I mean, I can tell a story, but not

like Dave.

Iíve known Dave

Grohl for over 15

years. In that time,

heís taken my bands

on tour; heís had me

and my girl over

for dinner parties,

costume parties,

birthday parties,

and drinking

parties. Heís even

sung me happy birthday, but heís never EVER told

me he loves disco drumming, and thatís how this

conversation began. I donít really want to call it an

interview, because itís more of a mission statement

to me: how to make rock and roll do just that. Dave

talking about music and drumming, and doing it

the way he always does, with humility and humor,

and itís more of an honor to be a part of that than

than anything else. To hear Dave tell a story is to be

there, and sometimes itís just about friends or his

kids, but no matter what, you find yourself smiling

the whole time. I hope you can feel the energy that

was in the room. I mean, I can tell a story, but not

like Dave.

Dave Grohl: Drum interviews are always funny

with me, I donít know what Iím talking about.

ATOM: Címon dude, whatever, Iím just gonna get into

it. Okay, my favorite thing about your playing is that you

always seem to find this perfect balance between playing

stuff thatís really really fun for drummers to listen to and

fun for drummers to play. And you do it without ever

taking the song out of the groove or get away from what

the song is doing, where itís going...

DG: You know, I think there are a few genres where

the drummers are totally underrated, one of them

being disco.

ATOM: What?!?

DG: And the other one being punk rock.

ATOM: I did not see that coming.

DG: Well yeah! Iíve always been a huge fan of disco

drumming.

ATOM: Really.

DG: For Sure! Gap band, Tony Thompson/

Chic drumming, Jr. Robinson, Micheal Jackson

drumming, like real groove drumming. Iíve always

been a huge fan of it, as Iíve always been a huge fan

of programmed drumming too. Like Liam Howlett

from Prodigy, how he programs dance beats is great

because it doesnít necessarily have to be the focus

of the song, it can just be the groove. Itíll make you

move as you focus on a lyric or itíll make you move

as you hum a melody or something. Itís so effective

in its simplicity that you donít have to raise your

hand and go, ďHey, Iím the drummer...Ē

Yeah, and at the same time, I have a lot of respect

for the real masters. You know, the drummers

who take control of a song, anyone from Krupa, to

Buddy Rich, the greats.

ATOM: Neil Peart...

DG: Well yeah, the first time I heard Rush was

the first time I really noticed the drums in a song.

When I was a kid I listened to the Beatles, rock

and roll, classic rock and AM radio was huge for

me, I loved all the AM radio.

ATOM: Like all the news stationsÖ

DG: Yeah, the traffic reports (makes traffic alert

sound) and like Helen Reddy and Carly Simon

and Phoebe Snow and Gerry Rafferty and 10cc

and all the real melodic í70ís AM rock music. I

loved that stuff because of its melody, but it

wasnít until I heard 2112 that I really started to

notice the drums, as like the focus of a song or

a drummer that was really kind of charging the

track. At that point I really hadnít gotten into The

Who yet either.

ATOM: Were you playing drums then?

DG: No, I was playing guitar, but I always kind

of understood what drummers were doing, for

whatever reason. I always knew that, like this

foot is the kick and my left hand was the snare,

right hand is a cymbal, I always knew that from

watching the Woodstock movie when I was like

8 years old. My first drum lesson didnít come

from a teacher. One the first things I learned with

independence was from the movie score from

Halloween.

ATOM: WHAT?

DG: Well, there was this one scene where sheís

being chased through the house, and thereís this

piano, dun, dudun, dun, dudun...and then this

synthesizer comes in going din din din din din...

(he starts to play this and sings) and I spent an

afternoon trying to get my hands to do that, and

when I figured that out I was like holy crap, I

could be a drummer! This is great!

ATOM: Youíre so funny.

DG: HA! Yeah, so anyway, Iíve always been a

groove person, and you might not think that

because of the kind of music Iím known for

playing.

ATOM: But I definitely DO think that, and thatís

what Iím saying, you still make it so thereís always the

groove or part, itís interesting for drummers to listen

to and want to figure out what youíre playing. And

for me itís not about flash or chops, itís just finding

that balance.

DG: I donít know what it is; I mean no two

drummers are the same. Everyone has their

signature fingerprint or their sound, the way they

play a drum set. I feel like so much of it has to do

with your hands. Itís easy to think that a drumset

would sound the same with different people

playing on it, when in reality, itís all in your hands

and balance.

ATOM: Well it kind of goes back to what we were

talking about in my truck, when you were saying

everyone should play and record themselves with one

microphone, and adjust their hands to make it sound

good, sound right.

DG: Yeah for sure! Itís good! Itís like getting a

tune up. I mean, once I discovered Led Zeppelin

records, I got really into the natural sound of

the drumset. A lot of albums I had at the time,

the drums didnít sound like drums to me, they

sounded like mics on things you were smacking.

Each tom and cymbal was separated and made to

sound its own way. So once I heard Led Zeppelin,

it sounded like a drummer in a room with a band.

Then once I learned mic placement and some basic

engineering, it only made sense to me, in order to

get that sound you had to play it that way. I would

record myself with just a few mics in a room and

to try and capture the sound of the drums. It really

comes down to your own personal equalization of

what youíre doing, rather than relying on a mixer

to do it for you.

ATOM: I want to back up a little bit, you hit on

something that I am really interested in, and that is

that you really do have your own sound. You have a

signature style and a recognizable sound and I think

there are only a handful of rock drummers who can say

that.

DG: You know itís funny, I always considered

myself to be a combination of all the different

drummers I grew up worshiping, so there are

things that Iíve lifted from Jeff Nelson of Minor

Threat, Tony Thompson, Reed Mullin from

C.O.C., John Bonham...

ATOM: Which era Tony Thompson was your

favorite?

DG: Just him, just his big flams, his drumming. I

got to meet him once and I said, ďHey I donít want

to sound like a total douche, but if it werenít for

youĒ...and I donít think I got to even finish what

I was saying and he was like ďI know man, itís

coolĒ.

ATOM: (laughing)

DG: (laughing) There was one day in a studio in

L.A. about 8 or 9 years ago, we had a big room at

Conway to ourselves for the day and we thought,

letís run tape and invite a bunch of our friends

over. So we invited Josh from Queens of the Stone

Age, Krist Novoselic was there, Matt Sweeney the

amazing guitar player was there and I was like,

letís call Keltner. So I called up Keltner and said,

ďHey man come down, weíre gonna mess around

and roll tape.Ē Heís a legend you know, his meter,

his vibe, heís a real vibe player you know. So he

comes out, sits down behind a drumset, and does

everything sideways, and backwards. And as

weíre jamming, I look over and heís got a stick

and a shaker in one hand, and a brush and a

frying pan in the other and heís playing the snare

with his foot or whatever. It was fucking crazy

what he was doing, but it had this sound. And

I watched it and I thought, THAT is messed up!

And then I listened to it, and I thought, ďTHAT

is genius!Ē And then I realized, people call Jim

Keltner because thatís what Jim does, he plays

like Jim Keltner. And for years whenever I went

into a studio to play with anyone Iíd be really self

conscious like, ďGod I hope Iím doing what they

want me to do, I hope it sounds right, I hope Iím

playing well.Ē And after watching Keltner do that

I thought, ďYou know what, from now on Iím just

gonna go in and play, like I would play.Ē I think

itís important to do that. You know, I never took

any drum lessons so honestly, I donít know much

about what Iím doing. I can hear it in my head,

and I can play most of the things I can imagine

in my mind or hear in my head, but I donít know

whatís right or whatís wrong, so I donít have any

boundaries.

ATOM: Youíre not restricted by any rules.

DG: Not at all, so I think thatís what makes people

do their own thing, when they donít feel like any

one thing is wrong, and you just do what you

do. But at the same time, I listen to myself and

think Iím just a super middle of the road generic

drummer.

ATOM: Thatís cute.

DG: Itís true! What Iím doing isnít any different

than what Rat Scabies was doing in the Damned.

He was washing his cymbals and beating the shit

out of them and playing 8th notes on the kick and

swinging his snare going through a rock song.

ATOM: But at the very least, you are aware of what it

is that makes it what it is, and a lot of people just gloss

over that stuff.

DG: Well, I also think itís different things like

where you place a stick on a drum, where you hit

the snare drum. I think most people without even

thinking about it, just hit it in the same place all

the time. Thatís gonna make your drums sound

different, thatís gonna make your playing sound

different. Where and how you play a cymbal,

where you land your kicks, mine are usually

behind. You know, all of those things together

are what make you sound the way you do. And

I think itís important that people appreciate that

about their own playing. I know some drummers

who wanna do everything right, players that want

to play perfectly, and I think a lot of times that

cripples your individuality, it takes away that feel.

Iíve heard people talk about feel for hours and I

donít think itís something you should talk about.

ATOM: It should just happen.

DG: You should just have it or, yeah, it should just

happen.

ATOM: Well, I guess what I want to know is, was

there ever a point when you acknowledged what you

were doing as yours?

ATOM: Well, I guess what I want to know is, was

there ever a point when you acknowledged what you

were doing as yours?

DG: When we made the Vultures record, there

were times when Josh (Homme), who I love and

who is a brilliant player and producer and an

awesome engineer, would push me to do things

that I wouldnít normally do. Typically, what will

happen in the studio is if you push someone hard

enough it will dead end and they will say, ďYou

know thatís just not what I do.Ē Iíve said it before,

Iíve heard people say it before and thatís a cop

out. I think I was all about that on the Vultures

record. There was one song called Reptiles, and

Josh wrote the song and programmed the drum

beat in Garage Band in his hotel room one day, and

it was the most insane drum beat Iíd ever heard,

it sounded like a fax machine, it was completely

random. And he said, ďHere, learn this.Ē And

Iím like...I...IÖitís like if you asked me to read

you a paragraph in Japanese or something, I just

canít do it. And I struggled with it, I struggled

with it. I canít read music, so I have to memorize

everything I play. I tried, and it was so bizarre,

just arbitrary random bulls#!, and I wanted to

give up ten times, and then I got it. And I was

like, ďThatís my favorite thing Iíve ever done!Ē

Because, it doesnít sound like anything else Iíve

ever done, and thatís what I like about it. So, if

you donít throw away any of those dead ends or

walls that you run into, it helps you grow a lot. I

love that song now, itís insane!

ATOM: Itís hard to play is what it is...

DG: Itís totally hard to play. I blew it live many

a time. Also, you know the Vultures record was

really nice because the type of music we were

making was different from anything else I had

done before. The closest thing was probably the

Q.O.T.S.A. record. I hadnít played drums on an

album in a long time, so I was totally starting

from scratch. So, I played differently and itís was

great.

ATOM: Do you notice that if you havenít been playing

drums for a while, that when you come back things are

different, some things are easier and some are harder?

DG: Shit yes! When weíre on the road, there are

drummers everywhere and I can tell you who is

sitting down at what drumset within 15 seconds.

Because most drummers sit down, they adjust

their seat and they do the same damn roll they

do every time just to get comfortable. And itís

understandable, I do it too I think. But itís nice

to get away from your instrument and forget

everything for a while, because then when you

come back to it you have this fresh perspective,

clean slate. You might approach it differently and

you might come up with some new tricks, without

losing all the old ones.

ATOM: You donít practice when youíre notÖ

DG: Honestly dude, Iíve probably practiced...

and Iím not saying this because Iím proud of it...I

donít like to play the drums when thereís no other

musicians around to play with. I donít like to

play by myself in a room, I like to play with other

people. I probably should (laughs) sit down and

learn some stuff. About 3 or 4 years ago I bought

a little pad, a practice pad. I wanted to learn how

to bounce my sticks (laughs). I donít know how to

do that, so I sat there trying to do press rolls, and

I gave up after two hours going, ďThis is bullshit.

That ainít gonna be loud enough!Ē

ATOM: Youíve always written songs, and over time

youíve, I guess, honed your skills as a songwriter. I

mean, now you are a Grammy award winning songwriter. So, have you noticed your approach to drums

parts has changed?

DG: Yeah, I think so. I donít really know how

much.

ATOM: Do you ever listen back to recordings and go,

ďOh, damn!Ē Like, would you do it differently now,

knowing what you know?

DG: I think Iíve always put focus and emphasis

on pattern, composition and arrangement, even

when I was playing hardcore, but that was mostly

out of the basic need for structure. Itís so we could

all keep the song together; this drum roll means

weíre about to go into the chorus, this drum riff

means the song is about to stopÖand I would

just do it every time so that the band wouldnít

mess up, and Iíve always had a great appreciation

for the songs that make you want to air drum. I

think itís cool and also kind of funny to see drunk

motherfuckers in a bar air drumming to ĎBack in

Blackí or ĎAbacabí. Thatís important to me because

what happens is, you have people who are

listening to drum riffs, so write one of those riffs.

To have a classic drum riff is every drummerís

dream; to have that one part, where that guy who

doesnít play the drums does it when the song

comes around.

ATOM: Heís just listening to music, he doesnít know

why heís doing it.

DG: He doesnít know dick about the drums, but

he knows that one drum break in "You Shook

Me All Night Long". So to me, thatís a good

example of drumming as songwriting. That sort

of composition, that simple ear candy becomes a

hook. So, I started taking that into consideration

more and more as the years went by; you know,

I donít really make acid rock; I donít really make

spacey 10-minute long Yes songs. I grew up loving

Buddy Holly and the Beatles; the two and a half

or three minute sweet songs, and Nirvana was

the same way; just to keep it simple and make it

so that thereís stuff thatís really memorable and

effective. So, I started using that in a lot of drum

arrangements too.

When I did the Q.O.T.S.A. ďSongs for the DeafĒ

record that made a big difference, it changed a lot

for me. It was the first time Iíd made an album

where the drums and the cymbals were separated.

So we did the basic tracks first, guitar, bass and

drums live in a room, no click track.

It was just the three of us, I had no cymbals, I had

these cymbal pads and I knew that I had to go

back and overdub all of the cymbals, so I really

had to focus on what I was doing, because I had

to remember what I had a done over a week and

a half. Eric Valentine, whoís a great producer, he

really worked with me on building a lot of those

parts.  A song like ďNo One KnowsĒÖ.the first

drum roll in the chorus...the second

drum roll in the chorus...the third drum

roll in the chorus, itís meant to build like

that, but also, everything was patterned

so that I wouldnít have a hard time

overdubbing the cymbals later. Thatís

when it really hit home that for that type

of music, writing those parts and trying

to make those hooks really makes the

song even bigger. Itís the same thing

here, when weíre making a Foo Fighters

record, we spend a lot of time trying to

construct a good pattern that builds from

the beginning of the song to end with

Taylorís drumming. Taylor has a great

sense of composition, and when I come

in with a song, itís usually really easy to

say, ďIt should go from here, point A to

point B, build up or break down here and

here,Ē and then itís just a matter of dynamics.

A song like ďNo One KnowsĒÖ.the first

drum roll in the chorus...the second

drum roll in the chorus...the third drum

roll in the chorus, itís meant to build like

that, but also, everything was patterned

so that I wouldnít have a hard time

overdubbing the cymbals later. Thatís

when it really hit home that for that type

of music, writing those parts and trying

to make those hooks really makes the

song even bigger. Itís the same thing

here, when weíre making a Foo Fighters

record, we spend a lot of time trying to

construct a good pattern that builds from

the beginning of the song to end with

Taylorís drumming. Taylor has a great

sense of composition, and when I come

in with a song, itís usually really easy to

say, ďIt should go from here, point A to

point B, build up or break down here and

here,Ē and then itís just a matter of dynamics.

ATOM: Is there a favorite thing youíve played on a

recording?

DG: Well, Nirvanaís Nevermind, I still listen to it

now. Iím a high school dropout, but Iíd imagine

that itís the same feeling as the last day in High

School. I look at it like, we were kids and it was

fun and easy to do, and it was really simple and

I wouldnít change a thing. Itís, you know, such

a simple record, I think maybe the easiest record

Iíve ever made in my life. Iím not kidding! It was

so simple! I listen to it now and itís like looking at

a picture of yourself when youíre like 19 or 20 you

can see in your face like, god, I was such a dumb

kid having a blast!

Then thereís the Vultures record. I listen to it and

Iím really proud of the drumming. Well, Iím really

proud of the record because I got to play with

fucking John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin!

ATOM: Did you ever just trip or have moments of

clarity like, what am I doing here?

DG: Oh dude, every night! Oh yeah, on the bus

in the morning, on stage, on planes. The Vultures

record was a blast to make because I got to

play with John Paul Jones and I felt like we had

connected, and had become a rhythm section.

Heís really good (laughs)...heís pretty good...

ATOM: Did he inspire you or encourage you in any

certain direction?

DG: Well yeah, apparently John would be the

guy who would stay in the studio after Zeppelin

would record a song and help the engineer and

edit the drum parts together. Hard to imagine

Zeppelin had to do any editing at all. But they

did, and John, because his meter was so great, he

just knows when itís right.

Oh god, there was this one song that we didnít

release, it was such a bitchiní drum track it was

really groovy, like maybe the grooviest thing on

the whole album...and it went: (sings and plays

this long phrase that is sick..I wish you could hear

it too...ATOM). It was bitchin...it was so cool, but

to get it, we played it a ton. You know, John could

play it once and it would be amazing, but for me

to really get it tight and in the pocket and right

in the groove with John, it took me a while. It

was like ten or fifteen takes, until finally I was

like, ďI think I got it...I think we got it...should

we listen?Ē And John says, ďYeah letís listen,Ē

and Iím listening to it and Iím like, ďYeah, yeah

I think I got it!Ē Iím like, ĒOh Shit this is it!Ē

And it sounds great and I turn around and look

at John and heís kinda scratching his chin, looks

at me, and he just shook his head and says, ďYou

didnít get itĒ (laughter). So, if youíre lucky, in

your lifetime youíll get to play with a bass player

that makes you sound better. I donít know who

was following who, it just fit and clicked, and if

I was ever in a place where I needed someone to

help me out I would just turn to John and watch

him. And there were also times when we would

jam and he would throw out some crazy African

shit at me.

ATOM: Idea-wise?

DG: Just like time. Heíd show me a riff and weíd

start playing it and hitting accents, and usually

live we would just jam. There was song structure,

but there was a lot of room for the two of us to

just jam and goof off. And there were times when

I would just look at him and go, ďI donít know

what youíre doing right now.Ē There was one

jam in the studio and he was doing some African

crap and I donít know what it was. I just stopped

and said, ďI havenít the slightest clue what youíre

doingĒ and I stopped!

ATOM: That takes some confidence too, to just say, ďI

donít get that.Ē

DG: Honestly, before we went in to make that

record, of course I was a little nervous, I have

Zeppelin tattoos! You know Iíve listened to his

records forever and then I realized, heís already

played with the greatest rock and roll drummer

of all time, so I donít have to walk in there and

try to be his favorite drummer, Iíll just go in there

and play the way I play. Iím not gonna be the best

drummer heís ever played with, Iím not gonna

be his favorite drummer in the world, so Iím just

gonna do my thing, and it worked out really well

that way. Thatís not to say that I wasnít terrified

9/10ths of the time, but it was fuckin' FUN to play

with John. Iíve never experienced anything like

that before.

Iíve known Dave

Grohl for over 15

years. In that time,

heís taken my bands

on tour; heís had me

and my girl over

for dinner parties,

costume parties,

birthday parties,

and drinking

parties. Heís even

sung me happy birthday, but heís never EVER told

me he loves disco drumming, and thatís how this

conversation began. I donít really want to call it an

interview, because itís more of a mission statement

to me: how to make rock and roll do just that. Dave

talking about music and drumming, and doing it

the way he always does, with humility and humor,

and itís more of an honor to be a part of that than

than anything else. To hear Dave tell a story is to be

there, and sometimes itís just about friends or his

kids, but no matter what, you find yourself smiling

the whole time. I hope you can feel the energy that

was in the room. I mean, I can tell a story, but not

like Dave.

Iíve known Dave

Grohl for over 15

years. In that time,

heís taken my bands

on tour; heís had me

and my girl over

for dinner parties,

costume parties,

birthday parties,

and drinking

parties. Heís even

sung me happy birthday, but heís never EVER told

me he loves disco drumming, and thatís how this

conversation began. I donít really want to call it an

interview, because itís more of a mission statement

to me: how to make rock and roll do just that. Dave

talking about music and drumming, and doing it

the way he always does, with humility and humor,

and itís more of an honor to be a part of that than

than anything else. To hear Dave tell a story is to be

there, and sometimes itís just about friends or his

kids, but no matter what, you find yourself smiling

the whole time. I hope you can feel the energy that

was in the room. I mean, I can tell a story, but not

like Dave.

ATOM: Well, I guess what I want to know is, was

there ever a point when you acknowledged what you

were doing as yours?

ATOM: Well, I guess what I want to know is, was

there ever a point when you acknowledged what you

were doing as yours? A song like ďNo One KnowsĒÖ.the first

drum roll in the chorus...the second

drum roll in the chorus...the third drum

roll in the chorus, itís meant to build like

that, but also, everything was patterned

so that I wouldnít have a hard time

overdubbing the cymbals later. Thatís

when it really hit home that for that type

of music, writing those parts and trying

to make those hooks really makes the

song even bigger. Itís the same thing

here, when weíre making a Foo Fighters

record, we spend a lot of time trying to

construct a good pattern that builds from

the beginning of the song to end with

Taylorís drumming. Taylor has a great

sense of composition, and when I come

in with a song, itís usually really easy to

say, ďIt should go from here, point A to

point B, build up or break down here and

here,Ē and then itís just a matter of dynamics.

A song like ďNo One KnowsĒÖ.the first

drum roll in the chorus...the second

drum roll in the chorus...the third drum

roll in the chorus, itís meant to build like

that, but also, everything was patterned

so that I wouldnít have a hard time

overdubbing the cymbals later. Thatís

when it really hit home that for that type

of music, writing those parts and trying

to make those hooks really makes the

song even bigger. Itís the same thing

here, when weíre making a Foo Fighters

record, we spend a lot of time trying to

construct a good pattern that builds from

the beginning of the song to end with

Taylorís drumming. Taylor has a great

sense of composition, and when I come

in with a song, itís usually really easy to

say, ďIt should go from here, point A to

point B, build up or break down here and

here,Ē and then itís just a matter of dynamics.