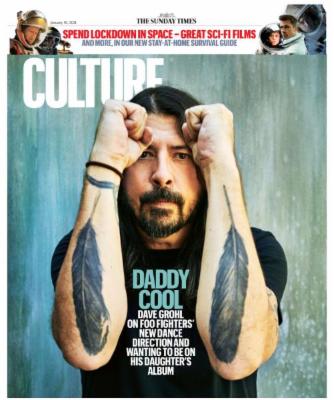

Even on Zoom Dave Grohl's brio and bonhomie leap out of the laptop screen. When we talk it is teatime in London, the sky outside already pitch-black, the temperature plummeting. By contrast the frontman of Foo Fighters and former drummer of Nirvana is greeting a new day from the sun-soaked veranda of his oceanfront home in Hawaii. Masochistically I request a quick peek and Grohl, sparking up the first of several early-morning smokes, flips his camera round to show a scene of enviable beauty and tranquillity, with perfect, palm tree-fringed lawns sloping down to the sea.

Even on Zoom Dave Grohl's brio and bonhomie leap out of the laptop screen. When we talk it is teatime in London, the sky outside already pitch-black, the temperature plummeting. By contrast the frontman of Foo Fighters and former drummer of Nirvana is greeting a new day from the sun-soaked veranda of his oceanfront home in Hawaii. Masochistically I request a quick peek and Grohl, sparking up the first of several early-morning smokes, flips his camera round to show a scene of enviable beauty and tranquillity, with perfect, palm tree-fringed lawns sloping down to the sea.

"I've been hanging out here for about 15 years," the 51-year-old says. "Usually we fly down for family vacations. The kids have spent their entire lives coming here, swimming with turtles. It really is paradise." I sort of hate you for this, I tell him. "I'm sorry," he says, chuckling. "But you did ask."

The last but one time Grohl, his wife, Jordyn Blum, and their three daughters flew here from their Californian base was for spring break, shortly after he had put the finishing touches to the Foos' tenth studio album, the swaggering and sinuous Medicine at Midnight, which is finally being released next month. Everything was ready to go, he says ruefully.

"The world tour was booked, the T-shirts were printed, the trucks were being loaded with equipment. The idea was to have a family vacation for two weeks and then I'd hit the road. That was March 15. And we stayed for three and a half fucking months. As idyllic and wonderful as it was, I was going stir-crazy, having calls and meetings once a week, saying, 'OK, when do we let this thing out of its cage? When is the ideal time to release this record?' After months and months of realising there is no ideal time, I came to the conclusion that we need to release the record to the people because we made it for it to be heard."

Grohl and his five bandmates had resolved to challenge themselves; efficient - and, to the group's detractors, sometimes generic - stadium rock was out. "The idea was to make something people could dance to. Before melodies, before lyrics, I knew I wanted to make this our boogie record. Because we'd never done that; we'd done noisy punk rock shit, dissonant heavy thrash, gentle, orchestrated acoustic balladry, and everything in between. The one thing we'd never done was really explore groove."

Is he worried about fan reaction? A throaty laugh. "It's hard to put the words dance and Foo Fighters in the same sentence because it just seems unimaginable. It's nauseating, really - if you told someone Foo Fighters had made a dance record, they would probably vomit. But I still have this idealistic and possibly naive attitude that we can do anything we put our minds to."

Grohl won't quite concede that the Foos had got caught in a comfortable rut, but he does imply that a change of gear was overdue. "Every musician begins with an instrument on their lap and an album on their turntable, their only dream being that they can make it to the end of the song without making a mistake. And there really is no right or wrong. But if you wind up in a place where people expect something specific of you, you can end up in a confined place of right or wrong - and guilt. Musical guilt makes no sense to me; I don't believe in guilty pleasure, I just believe in pleasure. And we didn't go and make a Britney Spears record. But we did manage to push out a little more, in order to grant ourselves not just freedom but happiness."

Channelling Inxs and the David Bowie of Fame, Fashion and Let's Dance, with a side order of solo John Lennon, Medicine at Midnight was intended as a 25th anniversary celebration, before the pandemic put paid to their plans. Lyrically, tracks such as Waiting on a War and No Son of Mine are bracingly polemical. The former was inspired by a conversation Grohl had with his middle daughter while driving her to school.

"She was worried about war, she'd been watching the news, and at the time there were international conflicts to do with North Korea and Russia. And I immediately went back to being her age, 10 or 11, in the Reagan era, and how I was terrified we were all going to die in a war. I'd have dreams of missiles flying overhead, of soldiers in my backyard. I lived in fear of there being a nuclear holocaust. I grew up just outside Washington DC and I always imagined that if it was going to happen, it would happen there first."

The furious No Son of Mine inverts the idea of a strict father, raising his child in fear of sin and transgression. "I wasn't raised with religion, I never went to church. But I was sent to a Catholic school for two years as reform when I was a teenager. It was the first time I'd cracked a Bible. My religion was my record collection, I looked at those musicians as my saints and their songs as my hymns."

Grohl initially started Foo Fighters as a solo project after Kurt Cobain's suicide in 1994. Numbed by Cobain's death, he locked himself away in a studio and buried himself in work. All these years later, it's a period he admits he remains haunted by, and something he and the Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic still discuss. "The difference between a conversation that he and I would have, versus a conversation that someone else might have about Nirvana, is that to us it was a personal experience, shared by three people. The music was almost secondary.

"Still, to this day, I'll see a new artist in their early twenties having to navigate success and feel concerned for them. Because at that point in life it's hard for anyone to be prepared for the . . . the trauma that comes with it. I look back, I think I was 22 when Nirvana became popular, and obviously I didn't bear the same weight that Kurt did, but I had an incredibly naive attitude, like, 'Oh my God, I have a credit card now. I can take my friends out for drinks. I can have my own apartment!' It sounds ridiculous, but my experience was as simple as that."

For all the Foos' enduring, multiplatinum success, Nirvana continues to follow him round, like a "Just married" can attached to the back of a car. Grohl says he has made his peace with this. "Over time you just get used to the noise of the cans rattling down the street behind you. The transition from Nirvana to Foo Fighters was difficult in more than a few ways. One, I had to go from hiding behind a huge set of drums with my head down and hair in my face, just there to make a fucking racket, to standing in front of a skinny pole, with the responsibility of giving people their money's worth. All of that was complicated.

"But more than that there was the rocky path of realising what we had recently been through that put me in that place. And it's not even musical; it's a personal experience that was difficult. You know, I was afraid of breaking down in tears in front of journalists if they so much as mentioned Nirvana. Because those types of things take years and years and years to process, and if you're really lucky maybe someday you'll come to terms with it."

Grohl, long described as "the nicest man in rock" (you will struggle to find anyone with a bad word to say about him), is also keenly aware of what his time with Cobain and Novoselic gave him. "I know I wouldn't be where I am today had it not been for Nirvana; the time we played together is the most incredible thing that's ever happened in my entire life. So much so that it would be easy to just stay there for ever, to be stuck there. But I've never been a person who just retreats and stays in a comfortable place. I've always been one to move on. And I realised, after Kurt died, that the only true healing would come from acknowledging that my life goes on and I have to find something new."

Is his role in Foo Fighters that of a benevolent dictator? "I'm just going to say yes," Grohl says, laughing. "I've been dodging that question for years." He's having to learn to step back with his eldest daughter, however. "She's 14 and already in a deep Bowie phase. I'm not talking about Eighties Bowie or Nineties Bowie - she hasn't even got to Berlin. All she does is listen to live bootlegs of the Station to Station tour.

"Or I'll hear Cocteau Twins coming out of her bedroom. And the Passions. Remember them? I'm in Love with a German Film Star. She was born with perfect pitch and a soulful voice and a musical memory that is photographic. She has all the tools she needs. She writes, I see her notebooks and the lyrics she's written."

Nothing wrong with that, yet Grohl admits to pangs of guilt. "Part of the thing about becoming a musician is the drive that gives you the desire to do it. In that sense I may be her biggest handicap. Like, she's got to be my fucking daughter? So I try to stay away. But I did ask her the other day, 'If you were to make a record, how do you imagine it would sound?' And she said, 'You know, I think somewhere within that shoegaze thing. Oh, and Dad, I need to get this new guitar pedal. It's called Loveless, and I want my guitar to sound like My Bloody Valentine.' I was, like, 'Yes. Yesss!'" Barely a heartbeat of a pause. "I will admit that my next reaction was, 'Can I be on your record, please?'"

Words: Dan Cairns