The only cloud on Hawkins’s horizon is the telephonic presence of Q, about to ask some questions about the new Foo Fighters album. As a member of the Foo Fighters, Hawkins might seem well qualified to answer. Unfortunately for both Hawkins and Q, he has clearly been briefed not to discuss anything beyond the basic facts released thus far: that on 10 November, the Foo Fighters release a new album, Sonic Highways, featuring eight songs written and recorded in eight different American cities – Austin, Chicago, LA, Nashville, New Orleans, New York, Seattle and Washington, DC. According to the record company statement, each song features “local legends sitting in”. Q asks Taylor who the guests are. “You don’t know? Am I supposed to tell you?!” He laughs. “Why me? I always shit the bed! I was the first person to tell the world Dave Grohl was having his first kid and I didn’t even mean to. ‘No, I don’t think there’s any tours for a while cos Dave’s having a baby!’ He called me the next day: ‘You dumb-ass!’”

So who are the guests?

So who are the guests?“Ahhhh… I’m not telling you! I don’t know if I can, dude!”

The sticking point is the “other” Sonic Highways: an eight-part series of documentaries, directed by Dave Grohl, each detailing through interviews with key figures the musical history of the same cities the Foo Fighters recorded in. With each song, Grohl wrote his lyrics at the 11th hour, “so as to be inspired by the experiences, interviews for the HBO series, and other local personalities who became part of the process”, the official statement says. One of these “local personalities” happens to be US President Barack Obama. The series premiered on 17 October; but for now, in late-September, every utterance the Foos make about their new LP is subject to a latticework of press embargoes.

Q attempts a speculative run through a list of the documentary interviewees, as well as those featured in HBO’s YouTube trailer, to wobble Hawkins’s wall of silence. Dolly Parton or Chuck D? “No.” Bad Brains? “No. Although Dave did jam with Bad Brains.” Gibby Haynes from Butthole Surfers? “No.” Rick Nielsen from Cheap Trick? “Uhhh… yes. Take another guess.” Allen Toussaint? “No. Wait… who’s Allen Toussaint?” He’s a famous New Orleans songwriter and producer. “Oh. No.” Carrie Underwood? “Uhhh… no.” Bonnie Raitt? “[Silence]… I’m not answering any more!” Joe Walsh? “Yes! Yes! OK, that’s your last one, that was your last guess! Shit, I hope I haven’t fucked up and given away too much information. I bet you I fucking did…”

Ten days later, Taylor

Hawkins finds himself

amid a sweaty cavern

built into disused

railway tunnels

underneath London’s

Waterloo Station. The

surroundings are less salubrious than his

Californian mansion, but he actually seems

more relaxed locking down the Foo Fighters’

hallmark euphoria. Technically, this isn’t a

Foo Fighters gig; the tickets and flyers claim

that the band playing this House Of Vans art

space-cum-skateboard bowl are called The

Holy Shits. But such is the Foo Fighters’

commercial footprint today, almost exactly

20 years since their original conception as the

vehicle for Dave Grohl’s musical journey

beyond the triumphs and trauma of Nirvana,

that any prospect of playing a venue with

a roof, let alone a capacity of just 600, has to

be veiled in subterfuge and pseudonym.

It’s a well-established Foos tradition

to preface a new album’s release with

secret gigs, invariably under an alias: on

3 September, 1999 at the Troubadour club in

West Hollywood, guitarist Chris Shiflett

made his debut Foo Fighters performance

masquerading as a member of Stacked Actors

whose set featured three songs from the twomonths-

imminent There Is Nothing Left To

Lose album. Yet despite Sonic Highways being

at precisely the same state of pre-release,

there are no new songs from The Holy Shits

at the House Of Vans. Ditto the previous

evening at Brighton’s Concorde 2, and the

next, at Islington Assembly Hall. Not even

a private performance for participants in

the Invictus Games, held in the grounds of

Winfield House in Regent’s Park, home of the

US Ambassador Matthew Barzun (a big Foo

Fighters fan, apparently), can persuade the

Foos/Shits to unveil any fresh material.

The only breaches in this pre-release

omerta come with a couple of instrumental

passages, dropped into

the performances of The

Pretender and This Is A

Call. No mention is made

of their root sources –

Outside and Something

From Nothing, two of the

most incandescent tracks

on the Sonic Highways album. Bat-eared

fans might just recognise the latter snippet

from a brief excerpt in HBO’s Sonic Highways

trailer. The unavoidable conclusion is that

Foo Fighters are being gagged by the

television network. Even Dave Grohl,

a man whose diplomatic skills are positively

ambassadorial, admits to feeling annoyed.

“It is frustrating,” he nods, sipping tea

with Q the day after the Foos have rocked

Brighton. “I can’t fucking wait to play these

new songs. But one of the elements of the TV

show is the reveal at the end. Our fear was

that if you hear the song before seeing the

show, it might give away the show. But yeah,

it’s tight. Very frustrating.”

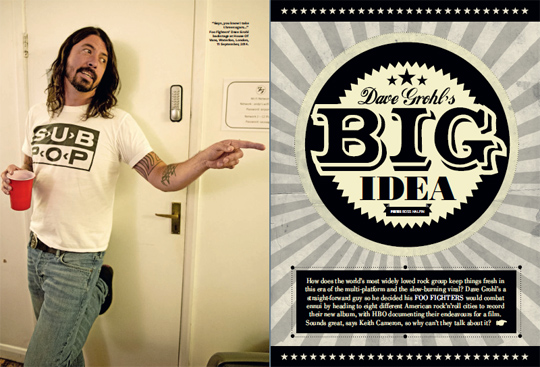

In the same week of the Foo Fighters’

semi-incognito London residency, U2’s new

album is launched as the surprise package in

an Apple press conference. This the era of the

multi-platform and the big reveal, where the

frisson of viral marketing and unconventional

delivery schemes can render the actual

creative content irrelevant. Meanwhile, fear

of online leakage turns the average corporate

entertainment giant into an Orwellian nexus

of paranoia. Frustrated he may be, but Dave

Grohl understands that when the world’s

biggest rock group is so desperate to

maintain market profile that it gives

its new album to people whether

they want it or not, his role is as

much a brand curator as a band

leader. His response to the U2

business model is a diplomatic shrug.

“Weeelll, I wouldn’t want to judge,”

he smiles. “I just saw that as, ‘Oh, of

course…’ I don’t think you have to do

something like the TV show to make a

record. There’s still great records made by

people in their living rooms. But I think it’s

important to consider moving outside of that

and doing more. Yeah, ultimately, this is one

hell of a fucking machine that’s gonna spray

this album everywhere… but you have to

balance that with substance. More than a

reality show, more than a live concert series.

It’s part of the reason that we got deeper into

the concept, because we would love people

to learn as much as be entertained. But I can’t

imagine just going into a studio and making

another record. It seems so boring to me.”

He may have earned his musical spurs

drumming for Scream amid the politically

righteous Washington, DC hardcore scene

that coalesced around Ian MacKaye’s

Dischord House during the ’80s (MacKaye’s

record label featured in the second Sonic

Highways episode), but Dave Grohl has

always been more sympathiser than activist.

Although some of Sonic Highways’ guest

contributors might seem bizarre – the

Preservation Hall Jazz Band, for instance –

the album conforms to its architect’s wellestablished

template: sugar-coated, flarednostril,

punk rock classicism. So common

sense suggests that after 20 years and more

than a thousand gigs, the Foo Fighters engine

needs a regular tickle up, to keep both

audience and band alert at the wheel.

During the band’s first decade, this

process occurred in organic, if chaotic,

fashion via personnel crises: drummer

William Goldsmith left in 1997 and was

replaced by Taylor Hawkins; guitarist Pat

Smear departed later the same year, replaced

by Franz Stahl, who was himself replaced in

1999 by Chris Shiflett. But since Smear

returned to the fold in 2006 the line-up has

been steady, and so Grohl has deployed

external devices to refresh one of the most

successful formulas in modern rock. After

that hardy perennial stratagem of the

acoustic tour and album, Grohl took his

stadium-busting troupe back to basics with

2011’s Wasting Light, recorded on analogue

tape in his garage. He also invited a film crew,

resulting in the feature-length documentary

Back And Forth. Beyond being an effective

promotional tool, the movie provided

a revealing insight into the Foo Fighters’

collective personal chemistry.

“James Moll, the director, did such a good

job, because he didn’t focus on the super-fan

trivia, but on the emotional connection

between the people in the band,” says Grohl.

“It’s one of the reasons why it took the album

and the band to another place, because

people understood us as human beings.”

Duly inspired, Grohl made his directorial

debut with Sound City, from which the Sonic

Highways series is a logical next step.

Ostensibly a documentary about the studio

where Nirvana made Nevermind as told

through interviews with a cast of luminaries,

Sound City also functioned as an

advertisement for Grohl’s own Studio 606,

the scene of the film’s all-star jam sessions, as

well as affording yet more persuasive screen

time to the Grohl brand of Everyman decency,

the stuff that got him saddled with that Nicest

Man In Rock handle. In truth, Dave Grohl

didn’t get where he is today without knowing

how to take care of business; it’s just that

instead of securing loyalty through fear of

being sacked, he inspires his fellow travellers

by engendering a harmonious working

environment and leading by example.

In so doing, Grohl earns his bandmates’

acquiescence to aspects of the job they might

prefer to avoid. Taylor Hawkins, for instance,

hates spending so much of his working life

being filmed, as demanded by the Foo

Fighters’ most recent two albums.

“I fought the wearing of the live-on-air

mics,” he says. “Dave would get mad at me

sometimes if I wasn’t playing ball.” The

drummer’s misgivings echo those of

musicians from the ’80s when coerced by the

emergence of MTV into making promotional

videos. “I don’t wanna be on a reality TV

show,” says Hawkins. “It’s never been one of

my ambitions to be famous for being on TV.

But I think Dave’s on the money. It isn’t

purely business ambition, because I know he

truly loves to do this: a project, to stress and

not sleep, to figure out how to make it better.

He loves that process. Just as I, on a much

smaller level, like the process of recording a

song. That’s not enough for Dave any more.

No, I don’t like being filmed, but it is part of it

now. I was telling the drummer in Jane’s

Addiction, ‘You guys need to make the

gloves-off real-deal documentary, so people

realise how important you are.’ You can make

a great movie about any band that’s had

something.” He considers for a moment.

“The Oasis movie would be kind of amazing,

don’t you think? I’d watch it!”

Wearing black patent

leather court shoes and

no socks, his face almost

perpetually amused,

there’s a decadent aura

about Pat Smear that

distinguishes him from

the other Foo Fighters. That and his age: at 55

he’s the eldest by at least 10 years. While his

bandmates enjoy typical all-American

outdoor pursuits, hiking and biking are not

his thing. On tour, he follows the same routine

regardless of city or country. “I stay in my

hotel room, usually with the curtains drawn,”

he says cheerily. “I never know where I am!”

Consequently, the Sonic Highways modus

operandi, which dictated spending six days

in each city, proved an eye-opener. Dave

Grohl’s criteria for choosing where to record

pinpointed places for which he and the others

felt a particular affinity – hence Chicago

(where the 13-year-old Grohl saw his first

gig), Washington, DC (near where Grohl

grew up in suburban Virginia) and Seattle

(Grohl’s hometown after joining Nirvana was

also where bassist Nate Mendel went to

university). LA was a logical choice, seeing as

all now live there, though only Smear can

truly consider himself a native. Of the

remaining four cities, Austin, Nashville and

New Orleans were chosen for the opposite

reason: the band had no obvious connections.

The LA experience was educational even

for Smear. Recording took place 90 minutes

outside the city, at Rancho De La Luna, the

home studio amid the high desert wilderness

of Joshua Tree famed for bacchanalian

sessions by Queens Of The Stone Age and

others. “I had never even been out in that

general area before,” says Smear. “So I didn’t

know what to expect. And it was not

something you could imagine, that’s for sure!”

As originally conceived, the Los Angeles

episode would begin in the city’s fleshpots

and then escape the glitz and glamour in

search of Joshua Tree’s frontier spirit. But

Grohl gradually realised that the pivotal

figure in the story was Smear himself, thanks

to his adventures as a dissolute teenager

on LA’s West Hollywood punk scene, where

he founded the Germs with the late Darby

Crash, a profound influence on the next

generation – most obviously Kurt Cobain, who

invited Smear to join Nirvana in 1993.

“I’ve known Pat for 20 years but

I don’t really ask him about the past,”

says Grohl. “For this episode we

walked around his old neighbourhood

and he told me about going to see the

Runaways for the first time, about the

history of the Germs, how he and Darby

met through a mutual speed dealer,

about meeting Alice Cooper and David

Bowie, chasing Freddie Mercury around

the Sunset Marquis Hotel… his life is so

extraordinary.”

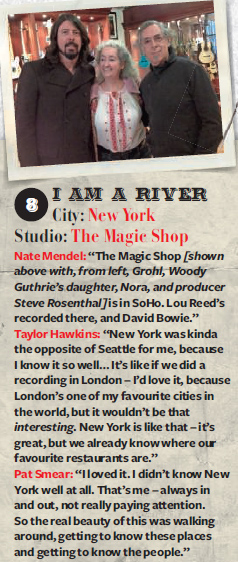

All agree that New Orleans offered the

most otherworldly experience (“the only

place I was sad to leave,” says Smear), thanks

to its unique melting pot of European and

Caribbean cultures, the cityscape’s

omnipresent musical undertow – and, as

Hawkins observes, “the fact that everybody’s

pretty much half-drunk all the time.”

But in terms of deep emotional resonance,

the most keenly anticipated Sonic Highways

rendezvous ought to be Seattle. The band

recorded at Robert Lang Studios, a reputedly

haunted facility built into a cavern. The

resident spook wasn’t the only ghost in

attendance: Robert Lang’s hosted the last

Nirvana recording session, in January 1994,

shortly before Kurt Cobain’s death. It was

here also that Dave Grohl came later the same

year to record the debut Foo Fighters album,

playing every instrument himself. For Sonic

Highways, the band recorded a song called

Subterranean. The mood, according to

Hawkins, was sombre. “I had a dark feeling

about Seattle,” he says. “The song is dark

and sad, it’s about the end of something.”

“There’s a lot of history in Seattle,” adds

Mendel, “for Dave and the band. It’s a

dangerous place for us, in a way, just not a

really comfortable city. Kinda had to go there

– it made sense as a city to go and record in.

But obviously there’s the tragedy of what

happened with Nirvana. We started there,

but left. A lot of people have got personal

histories there that are kinda fractured.”

For all that the

Sonic Highways

concept dictated a

documentarian’s

perspective on lyrics,

Subterranean feels

autobiographical:

it’s impossible to hear Grohl deliver such

lines as “Nothing left within… I will start

again” or “You might think you know me

but I know damn well you don’t” and not feel

the singer’s personal connection.

“I still love Seattle,” he says. “I spent

wonderful years there. Every time I go, I rent

a car and I drive by myself to all the old places

I lived, or the coffee shops or the bars. I don’t

want to forget my past, because it’s part of

who I am and I need to remind myself of

those things, good and bad. That studio’s

right down the street from where I used to

live. I had another life 25 years ago. I was a kid

in one of the biggest bands in the world.

And then everything was turned upside

down. My life completely changed when Kurt

died. It gave me a whole new outlook on just

waking up every day. I learned then that’s

what happens when someone close to you

dies. You have to begin again. Almost every

single day I think about Kurt.”

The guest musician on Subterranean is

Death Cab For Cutie’s Ben Gibbard. Just 17

when Kurt Cobain died, in the documentary

he talks of how his mother broke the news.

“She came into his bedroom, sat down next

to him, rubbed his back and told him,” says

Grohl. “He remembers breaking down,

and in the interview he starts to break down.

He said that day at school, all the freaks and

the punks and the nerds and the geeks had

a day off from the jocks bullying them. The

assholes left the Nirvana kids alone. What

a wonderful story. That meant a lot to me.”

Ten days after the Foo Fighters closed the

Invictus Games in London, Dave Grohl is

where you’ll usually find him when he’s not

on the road: at Studio 606, benevolent

master of all he surveys. It’s a rehearsal day

and Grohl taps his feet in anticipation as the

Foos’ crew check the gear and his bandmates

move into position. The clock says 10am but

he’s been on the go for hours, and not just

because the Grohl household got a new

member in August when his wife Jordyn gave

birth to baby Ophelia, the family’s third

daughter. “I’ve already had my pot of coffee

before the sun comes up,” he smiles.

His latest caffeinated brainwave is a

20th-anniversary re-enactment of the first

Foo Fighters tour, which saw the original

quartet supporting Mike Watt at such

storied entertainment palaces as the Dingo

Bar in Albuquerque and the Philadelphia

Trocadero. Not only does Grohl intend to

play the same venues, he insists the band will

use the same tiny van. Although nowadays

accustomed to executive class, he insists

this won’t be a problem. “We still like each

other. Still to this day, if the band needs to be

somewhere and three vans show up to drive

us, we all get in the one van.”

The feet tap. Last week he was editing the

LA Sonic Highways episode. Yesterday he was

at Apple’s headquarters. Doing what, one

wonders? “Oh, just talking! If there’s one

thing I’m excited about it’s spreading the

message of what we’ve been doing for the last

two years.” At Apple, he said hello to Jony Ive,

the London-born designer responsible for

every revolutionary device the company have

introduced. “Jony, how much do you sleep?”

Grohl asked. “I’m much better now,” replied

Ive. “Maybe five or six hours a night…”

“I went, ‘Wow, lucky bastard…!’” Grohl

laughs. “I make music because I wake up in

the morning like a fucking Space Shuttle, and

just start roaring. Every… single… fucking…

day. Within an hour and a half I have an

instrument in my hand.” He waves at his

fellow musicians, now regarding him

expectantly. “I feel a responsibility to do this.

When I look at Ian Beveridge, our monitor

guy, who’s been working with me for 25 years.

Or I look at Taylor Hawkins, or I look at Pat

Smear, or I look at the 40,000 people who

come to see the band play in a field, I don’t

want to let them down. All those people. I’m

here for them. Because what the fuck else am

I gonna do? Make movies?! Can you imagine

me trying to direct some pretentious male

model to emote?! Believe me, if there’s

a hell on earth, I think that might be it.”

History suggests we should hold him to that promise. For whichever Hollywood hotshot makes the documentary of Dave Grohl’s life, the title ought to be Expect The Unexpected: how a high-school drop-out, Nirvana’s self-styled “skinny muppet at the back banging shit”, became the guitarist, songwriter and life force of one of the world’s greatest rock bands, in the process confounding everyone’s expectations. Except his own. Twenty-five years down this personal sonic highway, a route that’s taken him from the Dischord House to the White House, Dave Grohl’s journey is far from over.

Words: Keith Cameron Pics: Ross Halfin