Inspired by The Police drummer Stewart Copeland’s deliberately mysterious 1980 album made under the pseudonym Klark Kent, Grohl had chosen a moniker that gave no clue whatsoever as to the music’s creator. Just like Copeland, Grohl had sung the songs and played virtually all of the instruments himself, sprinting from drum kit to bass to guitars to the microphone in a frenetic six-day burst of activity at the city’s Robert Lang Studios, overseen by his engineer/producer friend Barrett Jones.

“I mean, the sense of accomplishment just in picking up those cassettes…” Grohl recalls today, still buzzed by the memory. “I was so fucking excited. I was, like, 15 years old again. I’d sequenced it and picked the font for the cover and everything. I literally had them in the back of my truck and handed them to people at gas stations that I had conversations with. I was like, ‘Yeah, I got this new thing I did. Here, check it out,’ and I would give ’em a cassette.”

Dave Grohl had good reason to want to fly under the radar. It was just over six months since the death of Kurt Cobain and he was still reeling. At first, even sitting behind a drum kit only served to remind him of everything he’d lost with Nirvana. “Emotionally, it was tough just to pick up sticks,” he admits. “Before the Foo Fighters, I didn’t know what I was gonna do.”

Going back to the age of 11, Grohl had dabbled in home recording, crudely layering up his hissy performances via the medium of two cassette machines pointed at one another as he performed in-between them. Later, in Seattle, during the Nirvana era, he’d made solo tapes in his basement, released low-key in ’92 as a cassette album Pocketwatch, under the alias Late!. Like the Foo Fighters demos, they’d been made purely for fun and catharsis.

“I realised that it might be therapeutic in some way if I go and record in an actual studio,” he remembers. “Just to sorta have some sense of self-worth, or some, like, exorcism. Whatever it was, I was definitely not going in to make an album.”

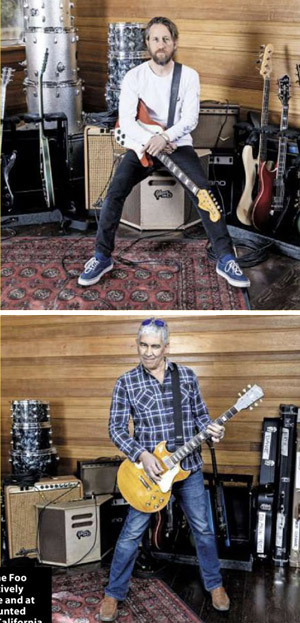

On a trip to Los Angeles, Grohl handed a Foo Fighters cassette to Pat Smear, Nirvana guitarist from the In Utero tour until the end. Smear was feeling similarly desolate and lost and had decided to quit music. “I was like, It’s too heartbreaking. I’m out,” he tells MOJO today. “I didn’t want to do it again.”

“Pat calls me back,” says Grohl, “and he’s like, ‘I love it, it’s so poppy.’ Which I’d never really even considered. I’m like, (incredulously) Is it? OK. I said, ‘Well dude, I’m gonna put a band together. I met these guys and d’you wanna play guitar?’ He’s like, ‘Oh my God, yes.’”

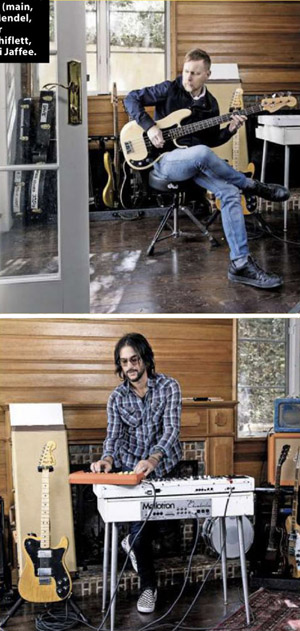

Grohl had been tipped off that the Sub Pop-signed, proto-emo Seattle band Sunny Day Real Estate were breaking up. After their final show, he approached bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith with a view to getting together with Smear and taking the Foo Fighters songs into the rehearsal room. Straight away, as Mendel remembers, “It was just like, This could turn into a great thing.”

Grohl had been tipped off that the Sub Pop-signed, proto-emo Seattle band Sunny Day Real Estate were breaking up. After their final show, he approached bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith with a view to getting together with Smear and taking the Foo Fighters songs into the rehearsal room. Straight away, as Mendel remembers, “It was just like, This could turn into a great thing.”How to debut the Foo Fighters live became the big conundrum, in terms of avoiding the bright spotlight tracking the next moves of the surviving members of Nirvana. The solution for Grohl’s new band: a return to their punk rock roots. In other words: a gig in a squat in a warehouse space above a fishing supplies shop in downtown Seattle. Crucially, there would be free beer.

“I remember Dave saying, ‘Let’s get a keg of beer and then they’ll like us,’” laughs Smear. “‘Let’s get ’em drunk.’”

“Make sure everyone’s fucking lathered and then play,” grins Grohl. “So, of course they’re gonna enjoy it.”

“We were terrible,” recalls Mendel, “but probably just made up for it with raw enthusiasm. It’s prior to Dave really feeling comfortable on the mike. So, I’m sure he said, like, ‘Hey, we’re the Foo Fighters,’ and that was probably it the whole night. It was over before anybody really knew it.”

“Honestly,” adds Grohl, “still to this day, I have a disconnect between Nirvana and the Foo Fighters. I don’t connect the two. So, I never worried about the expectation. But, still, I was fucking terrified, in someone’s loft. It becomes a baptism, y’know. Once you’ve done it, you can only go forward.”

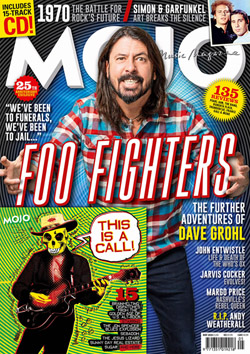

Close to 25 years on from the subsequent release of Dave Grohl’s exploratory tapes as the first, eponymous Foo Fighters album, Grohl sits in the control room of the band’s Studio 606 in the Northridge suburb of Los Angeles. The constant forward motion of the group from keg party debut to multimillion-dollar operation has brought him to this very point – sparking up a cigarette and a touch nervously readying himself to press play for MOJO on the latest batch of still-unmixed tracks for the Foo Fighters’ upcoming tenth long-player.

“I’ve never entered into an album process thinking, We’re the greatest, most amazing, biggest band in the world,” he offers, in-between comforting puffs. “You might convince yourself of that when you’re in a room listening to shit you’ve just recorded. But the second you fucking hit play in front of a roomful of strangers, you turn into a six-year-old kid with his pants down at school. Absolutely. You’re just like… (wheezes in fear).”

Immediately, the sounds that begin pumping out of the studio’s enormospeakers signal that we’re into entirely unexplored territory for Foo Fighters. Over the course of six work-in-progress songs aired for MOJO, funky Bowie influences abound (Let’s Dance; Fame), drum loops are conjured up out of finger-snaps and knee-slaps and female backup singers coo in support of Grohl’s characteristically sweet and salty vocals.

Other tracks work with more familiar blueprints – glittered-up glam rock, acoustic balladry building in tempo and density to fuzzy crescendos. But, overall, for a band who’ve up to this point painted in different shades of their trademark heavy pop, it’s surprising to hear them step out onto the dancefloor.

“I think so, yeah,” Grohl nods. “But, over time, I think you grow a little more confidence in what you do.”

So, it’s the Foos getting on the good foot?

So, it’s the Foos getting on the good foot?

“We’ve always been on the good foot, haven’t we?” quips Smear.

Tigger-ish drummer Taylor Hawkins, who joined the band in 1997, is more circumspect and clearly still trying to get his head around the band’s new direction. “We’ve kind of become the AC/DC of post-grunge or whatever,” he states. “So, the reaction is gonna be interesting. It’s the most pop fantastic record we’ve made.

“But I had a hard time making this record,” he goes on, “because I was like Roger Taylor in the Queen movie. (Adopts comedy English accent) ‘We’re resorting to drum loops?!’ I almost feel Dave likes chaos a little bit and then likes to control it.”

Underlining the sense of restlessness and experimentation that has fed into the Foo Fighters’ 25th anniversary album, it wasn’t even recorded at Studio 606. Instead, vanloads of recording gear were shipped six miles south-east of here to the sleepy residential area of Encino and a house that Grohl had initially rented to sketch his demos in isolation. “I need to know that there’s nobody around,” he explains of his preliminary creative process. “Like, not even a fucking gardener.”

Earlier in the day, Grohl had shown MOJO around the Encino house, with its crumbling stone steps, weathered walls and neglected, foliage-strewn pool. Current neighbours include Ice Cube, Steve Vai and Slash, while in the past Tom Petty, David Crosby and Dave Stewart all lived nearby. Grohl and band and crew members attest to the oddly eerie atmosphere of this particular property, especially as night fell during the sessions.

“It was different not doing it in a fancy studio,” explains laidback, Furry Freak Brother-ish keyboardist Rami Jaffee, a Foo since 2017. “Doing it in a creepy house in the [San Fernando] Valley. It was cold and kinda shady.”

“We wanted to think outside of the box,” says Grohl, “and record somewhere strange.”

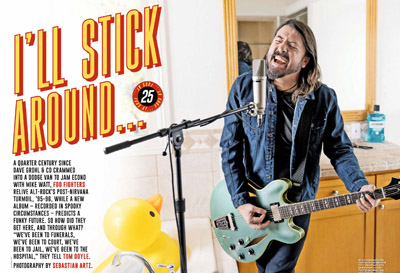

“Dave is always looking to not repeat himself,” says guitarist Chris Shiflett, who joined the band in 1999. “Not only musically, but just in terms of experience.”

No matter how far the Foo Fighters have travelled in a quarter of a century, some things have remained constant. Parked outside of Studio 606 is the same red Dodge van that the original four-piece crammed into for their first ever tour, back in the spring of 1995. It’s still very much in daily use. You can take the band out of the garage, et cetera…

“It’s still a garage band,” says Smear. “It really is. We just built a rehearsal studio next door. It was the garage. You go into that room and it’s like, ‘It’s a fucking garage (laughs).”

The second-ever Foo Fighters gig, in Arcata, California on February 23, 1995, was just as opportunistic and spontaneous as their squat party debut four days earlier. The band were in town mixing the Foo Fighters album with Rob Schnapf and Tom Rothrock (who’d recently co-produced Beck’s Mellow Gold), when Grohl spotted that a Beatles tribute band were playing at the local Jambalaya Club.

“We thought, Wow, let’s try that thing again where we get up and play these songs,” he remembers. “And we opened for this Beatles cover band. We made our own merch. We went to a thrift shop, bought 30 T-shirts that already had shit on them, made a stencil out of cardboard that just said ‘Foo Fighters’. Spray-painted all the shirts and sold them for five bucks. So, y’know, in our minds, we were starting from a really pure place.”

“We thought, Wow, let’s try that thing again where we get up and play these songs,” he remembers. “And we opened for this Beatles cover band. We made our own merch. We went to a thrift shop, bought 30 T-shirts that already had shit on them, made a stencil out of cardboard that just said ‘Foo Fighters’. Spray-painted all the shirts and sold them for five bucks. So, y’know, in our minds, we were starting from a really pure place.”

By this point, with massive major label interest roused by the Foo Fighters cassette, the group had signed to Capitol Records, drawn there by the presence of Nirvana’s former Geffen A&R man, Gary Gersh. Even so, Grohl had been advised by his lawyer to form his own record label, Roswell, and license the recordings to Capitol.

“When we were going and talking to record companies,” he says, “I didn’t necessarily feel safe with them all. Because I thought the first thing they’ll do… the fucking easy-out, cash-grab short game… is to just play the Nirvana card. And I did not want to do that. So, with Gary, I could trust him because he was there throughout the whole Nirvana thing. I knew that he’d take care of us.”

Grohl was also shrewd enough to realise that the Foo Fighters needed to find their road legs, and quickly. With that in mind, he booked them onto a two-month-long club tour sharing the bill with Eddie Vedder’s side project Hovercraft and former Minutemen bassist/singer Mike Watt.

For Grohl, it was a relative comedown from the sold-out arenas and festival headline slots of his Nirvana days. For Nate Mendel, however, four guys in a Dodge van was a luxury compared to being on the road with Sunny Day Real Estate. “We bought the van for $28,000 or whatever,” says the bassist, “which was an unbelievable amount of money [to me] at that time, ’cos [Sunny Day] never had a budget over five grand for a van.”

“When we first climbed in that van to do our first tour,” says Grohl, “I didn’t know if we’d do another one. We were opening for Mike Watt and we were also his band. If you’ve ever looked at a Mike Watt itinerary, you’ll know that it’s fucking eight shows a week and you have a day off every 10 days.” As Pat Smear recalls, Watt had a much-repeated catchphrase: “He always said, ‘If you ain’t playing, you’re paying.’ So, we were playing every night.”

Adding to the sense of schlep and slog was the fact that nightly Grohl had to face Kurt Cobain’s image staring up at him from fans’ T-shirts. Since the Foos hadn’t yet released any music, there were calls from the crowd for Marigold, the Grohl-written B-side to Nirvana’s 1993 single Heart-Shaped Box. Drawing a line in the sand, he refused to play it. “It was the only song they knew,” Smear accepts. “Nobody knew any of the songs. But every gig got a little bigger. So, it started out in just shitty, tiny punk rock clubs and then we ended up in old movie theatres and stuff.”

“I felt on that first tour,” says Grohl, “that there was a sense of, like, compassion in the audience. It was a lot more compassionate than you’d imagine. They were rooting for you.”

When Foo Fighters was released in July 1995, it was revealed as a record fizzing with Grohl’s exuberance and expertise. But fans and critics naturally pored over it looking for references to Cobain’s suicide and the demise of Nirvana. Opener, This Is A Call (“to all my past resignations”) was clearly the sound of someone putting his recent, troubled history behind him and thrilling in the prospect of an unknown future.

But it was the lyric of I’ll Stick Around that attracted the most analysis: its title wrongly assumed to be directed at Cobain. Only more than a decade later would Grohl admit that it was actually a song digging at Courtney Love (especially the lines, “How could it be/I’m the only one who sees/Your rehearsed insanity?”). “I was a little angry at the time,” he concedes today.

For all the goodwill surrounding Grohl and the Foo Fighters, there were pockets of resistance to the new group. “Like, ‘How dare you be in a band again?’” their singer recalls, his voice rising. “‘Your music’s fucking shit and that was a real band and you’re not.’ It’s like, You really think that’s gonna stop me? It only makes me wanna fucking do it more, y’know. So, you can keep it coming if you want, but I don’t give a fuck.”

Meanwhile, Grohl acknowledges the undeniable uplift that his time in Nirvana contributed to the rise of the Foo Fighters. “I’ve never been afraid to say that if it weren’t for Nirvana, the Foo Fighters wouldn’t be in the same position that we’re in now. We had an advantage right out of the gate that there was interest in the band because of that. I mean, it’s obvious.”

No more obvious in those early months than at the Foo Fighters’ second UK date – after a June one-off in London’s King’s College – at the Reading Festival on August 26, 1995. Ahead of the band’s bill-topping appearance in the second stage tent, fans crushed dangerously into the confined space, forcing the tent’s closure before the group arrived on-stage.

“That was nuts,” Smear says. “It probably wouldn’t have scared me hadn’t all the people that worked there been panicking, and y’know, telling us, ‘You gotta do this, you gotta do that.’ So, it wasn’t the horde, it was those people that made me scared of the horde.”

Fearing a catastrophic fan pile-up, the organisers quickly offered the Foo Fighters a slot on the main stage, above headliner Björk. “We’re like, ‘We’re not doing that,’” remembers Smear. “That’d have been pretty inappropriate at the time. We were just some new band, some new thing.”

“Yeah, it just didn’t seem right for us to jump on the big stage,” Grohl stresses. “We weren’t ready. Listen to it, dude. We sound like a fucking high school Battle Of The Bands third place rock band. Now I’m like, Oh God, people paid to see this? Fucking Christ.”

Jump cut to Seattle, seven months later, March 1996. With the Foo Fighters’ debut album nudging two million sales, this writer was in the city to interview the band for the first time. Over our three days together, Grohl was recognised almost constantly on the streets – less, it turned out, as the former drummer of Nirvana and more as the star of the video for the fourth Foo Fighters single, Big Me, stylised as a jokey commercial for a Mentos-like soft mint named Footos.

Back then, I tried to tiptoe around the unavoidable subject of Cobain – focusing instead on his legacy – knowing that Grohl had castigated other journalists for their lack of sensitivity. At the same time as trying to establish the Foo Fighters as their own entity, Grohl was living under the enormous shadow of his former bandmate and the growing myths regarding his death.

“The hardest part of that period when the first album came out was having to answer all of the unanswered questions about Nirvana,” he says now. “And so, it took its toll on me after a little while. The last thing I wanted to talk about was Kurt dying. So, I really shied away from answering those questions. And in writing lyrics I turned away from it, because I wasn’t ready or capable of expressing myself about that.”

Fame as a frontman in his own right was something else Grohl was struggling to adjust to. “It’s funny,” he says, “because every now and then I’ll see an interview of myself from those days, and I was shy, y’know. Compared to now. It took years and years before I really came out of my shell and felt, y’know, footed in the band and being a singer.”

Fame as a frontman in his own right was something else Grohl was struggling to adjust to. “It’s funny,” he says, “because every now and then I’ll see an interview of myself from those days, and I was shy, y’know. Compared to now. It took years and years before I really came out of my shell and felt, y’know, footed in the band and being a singer.”

Being the boss of his own label, Roswell, was equally problematic, now other bands were submitting their demos to him. “They’d say, ‘Oh my God, can we be on your label?’” he hoots. “And I could just imagine their master tapes or their press kit, like, under a pile of fucking McDonald’s bags and beer cans in my truck. I’m like, No, I don’t want to be responsible for the demise of anyone’s career but my own.”

Moreover, a smooth and steady rise to megaband status for the Foo Fighters was anything but a given. For Grohl, those early days were wracked with insecurities. “I don’t really know if anyone is ever going to be able to consider us a valid rock unit,” he admitted to me in 1996. “I’m a pessimist in some ways. Maybe after the next album people will think, ‘Jeez, these guys are for real and they’re not just this circus sideshow. They’re actually doing this for the long haul.’”

Looking back now, though, Grohl can certainly admire the chutzpah of his younger self. “I mean, a lot of what we do is me just standing on a cliff and proving to myself that I can jump. I can’t back down from something. I just can’t do it.

“But, yeah, there wasn’t a moment where I thought, I don’t wanna do this any more,” he adds. “That came much later (laughs uproariously).

In the long and sometimes turbulent flight of the Foo Fighters, the making of their fourth album, 2002’s One By One, was the point where they almost crashed. The initial sessions were stale and unproductive, the recordings overpolished and lifeless. Then the arguments started and Grohl parachuted out of the band to drum on tour with Queens Of The Stone Age. “There was friction in the band, we almost broke up,” he recalls. “That album, we had to do it twice. The second time in 12 days.”

One By One was swiftly re-recorded in a makeshift studio in Grohl’s house in Virginia, effectively returning the Foo Fighters to the garage, salvaging the group and winning them their second Grammy. Unsurprisingly, their leader recalls that particular awards ceremony with no little pride: “I’m looking at the sea of jewellery and glamour. I’m like, God, we were tacking egg cartons on the wall to make this thing happen.”

Five years later, in Los Angeles in 2007, Grohl confessed to me that suddenly being the head of this huge business – and responsible for the livelihoods of dozens of others – was a pressure that had forced him into therapy. “It might seem like the garage band,” he offered, “but there’s times where just everything becomes overwhelming and I need to fucking figure it out.”

These days he’s found his peace with being Foo Fighters CEO. He just lets others organise the spreadsheets. “I don’t know how much anyone gets paid in this band, at all,” he says today. “Everybody knows not to tell me. Because if you subtract that from the equation, it’s all heart and it’s no head. So, I know this is a massive business. I get it. But I don’t want to look at it like that.”

Far more exhilarating proof of the Foo Fighters’ status came in the summer of 2008 when they sold out two headline shows at Wembley Stadium. While Dave Grohl was visibly overcome at one point and broke down in tears, he walked tall as a frontman (and ran around a lot). The others, meanwhile, admit that they were utterly freaked by the scale of the gigs. Taylor Hawkins felt they were “too big” and that he was just “a scared kid up there”.

“Wembley was terrifying,” agrees Nate Mendel. “You’re like, I’m proud of the band… think we’re good… we’ve got some self-confidence. But that whole thing twice? There was a bit of a disconnect.”

“Moments like that, you’re just like, This is fucking insane,” Grohl enthuses, clearly more comfortable with the experience in retrospect. “I was just thinking, We’re getting paid more than my mother could make in 10 fucking years. Or 30. Maybe more than she’s ever made. Just for me screaming into a fucking microphone. Something that started with a demo tape I did down the street in six days.”

Grohl cites a later performance as the point where he finally swallowed all of his fears as a frontman. Namely, when he sang Wings’ Band On The Run at The White House in 2010 as President Obama and Paul McCartney watched from the front row.

“I was standing on the side of the stage waiting to go on, thinking, I hope I don’t faint, I hope I don’t puke, I hope I sing in key,” he remembers. “And I was so wracked with fear, I realised that I was wasting this incredible moment on that fear. And I was gonna lose the joy or the magic of just being there in that moment. And then the fear just kinda went away. So, now I have no fucking problem standing up in front of 150,000 people (laughs).”

Nonetheless, thinking back over 25 years of the Foo Fighters (“We’ve been to funerals, we’ve been to court, we’ve been to jail, we’ve been to the hospital…”) has reminded Dave Grohl of a recurring dream that he used to have during the days of the band’s first van tour.

“I dreamed that I was driving the van,” he says. “We were climbing up this hill and it was getting steeper and steeper, until it almost felt like the van was gonna flip over backwards. And I would always wake up right before the van fucking flipped over backwards.”

In truth, it isn’t a dream that would take a psychotherapist very long to interpret. The van equals the Foo Fighters. Still, after a quarter of a century climbing ever upwards, Dave Grohl has never flipped the band.

“No, never flipped the band,” he breezily acknowledges, his face lighting up. “Not yet!”

REPOSSESSED?

THE HOUSE IN WHICH THE FOO FIGHTERS RECORDED THEIR TENTH ALBUM CHILLED THEM TO THEIR BONES. "WE STARTED TO SEE THINGS WE COULDN'T EXPLAIN," RELATES DAVE GROHL.

"The Encino house was built, I believe, in the ’40s. In the ’60s and the ’70s, it was somewhat of a party house. Like, Joe Cocker would go there and party. We heard that a band recorded there 25 years ago. We hadn’t heard any of the recording, but apparently the sound in the living room was fucking amazing. When we first came to see the house, the vibe was definitely off. We knew that it was a bit creepy. Y’know, some people believe in ghosts, some people don’t. Some people are receptive to bad vibrations, some people aren’t. But when you walked into this place, it was undeniable that there were cold spots. You had that feeling in the back of your neck like someone was standing behind you or watching you.

I lived in a house in Seattle that actually had a ghost in it. Things would move, you would hear footsteps. But the worst part was when you were downstairs in the house, you always felt like someone was right fucking behind you. And at night when you’d close your eyes, you felt like someone’s face was right here next to yours. That really fucked me up.

When we first came to see the house, the vibe was definitely off. We knew that it was a bit creepy. Y’know, some people believe in ghosts, some people don’t. Some people are receptive to bad vibrations, some people aren’t. But when you walked into this place, it was undeniable that there were cold spots. You had that feeling in the back of your neck like someone was standing behind you or watching you.

I lived in a house in Seattle that actually had a ghost in it. Things would move, you would hear footsteps. But the worst part was when you were downstairs in the house, you always felt like someone was right fucking behind you. And at night when you’d close your eyes, you felt like someone’s face was right here next to yours. That really fucked me up.Back in the summer of 1992, I’d hung out at the house where Sharon Tate was killed by the Manson Family. Nine Inch Nails was making their masterpiece there [1994’s The Downward Spiral, recorded at singer Trent Reznor’s then-home at 10050 Cielo Drive]. Nirvana was doing nothing so I came to LA to hang out with my friend Pete [Stahl, Scream singer] in his house. He had no air conditioning, in the Valley, in the summer.

So, my friend Bryan Brown and I decided we were just gonna go look for swimming pools. One day, Bryan said, ‘Guess where we’re fucking swimming today?’ I mean, I’d read all the Manson books when I was a teenager. I’d seen a million pictures and all of a sudden, I was there. And, absolutely, there were bad vibes. No question. Anyways, so when we walked into the house in Encino, I knew the vibes were definitely off, but the sound was fucking on. So, we started working there and it wasn’t long before things started happening. We would come back to the studio the next day and all of the guitars would be detuned. Or the settings that we’d put on the board, all of them had gone back to zero.

We would open up a Pro Tools session and tracks would be missing. There were some tracks that were put on there that we didn’t put on there. But just like weird open mike noises. So, nobody playing an instrument or anything like that, but just an open mike recording a room. And we’d fucking zero in on sounds within that. And we didn’t hear any voices or anything really decipherable. But something was happening.

It got to the point where I brought one of those nest cams that I still have at home, for when my kids would sleep in their cribs. I set it up overnight so that we could see if there was anyone there or anyone was coming to fuck around with us. At first, nothing. And right around the time we thought we were ridiculous and we were out of our minds, we started to see things on the nest cam that we couldn’t explain. Then when we found out the history of the house, I had to sign a fucking non-disclosure agreement with the landlord because he’s trying to sell the place. So, I can’t give away what happened there in the past. But these multiple occurences over a short period of time made us finish the album as quickly as we could.” Words: Tom Doyle Pics: Sebastian Artz