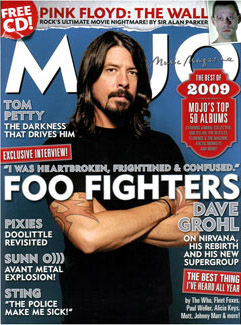

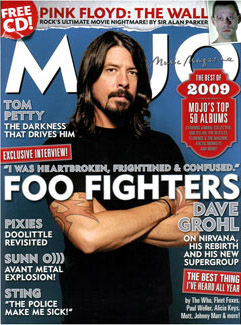

"I was heartbroken, frightened and confused."

Mojo

Hardcore changed his life, Grunge nearly destroyed it. These days Bob Dylan digs his songs, he's got Paul McCartney on speed dial and he counts a member of Led Zeppelin as one of his bandmates. In his most revealing interview ever, Dave Grohl reflects on 25 years of death, drugs and discord, and marvels at how "a little bastard from the middle of nowhere" became an unlikely American hero.

Saturday, July 3, 1983. It's a beautiful day in Washington DC and tens of thousands of American citizens are descending upon the Nation's capital for the annual Independence Day fireworks display on the Mall. But one local teenager has other plans. Fourteen-year-old Dave Grohl is bound for the Lincoln Memorial, in whose shadow 20 hardcore punk bands, among them Dead Kennedys, Reagan Youth, DRI and MDC (aka Millions Of Dead Cops) are due to play a free Rock Against Reagan gig.

Saturday, July 3, 1983. It's a beautiful day in Washington DC and tens of thousands of American citizens are descending upon the Nation's capital for the annual Independence Day fireworks display on the Mall. But one local teenager has other plans. Fourteen-year-old Dave Grohl is bound for the Lincoln Memorial, in whose shadow 20 hardcore punk bands, among them Dead Kennedys, Reagan Youth, DRI and MDC (aka Millions Of Dead Cops) are due to play a free Rock Against Reagan gig.

There are police everywhere, shining spotlights on the crowd from helicopters, patrolling the concert site on horseback, sitting on buses in full riot gear. As evening falls, the mood on the Mall darkens. The punks get mouthier, the tourists more confrontational, the police more aggressive, randomly cracking skulls with their billy clubs. Dead Kennedys walk onstage as the sun sets. Frontman Jello Biafra stares up at the lights flashing atop the Washington Monument and begins railing against "the great Klansman in the sky with his two blinking red eyes", the band crash into Holiday In Cambodia, 800 punk rockers roar their approval and Dave Grohl charges gleefully into the heart of a swirling circle pit. "I've got chills just thinking about it," he laughs. "It was like our own personal Altamont, our Woodstock. And that's when I said, Fuck the world, I'm doing this..."

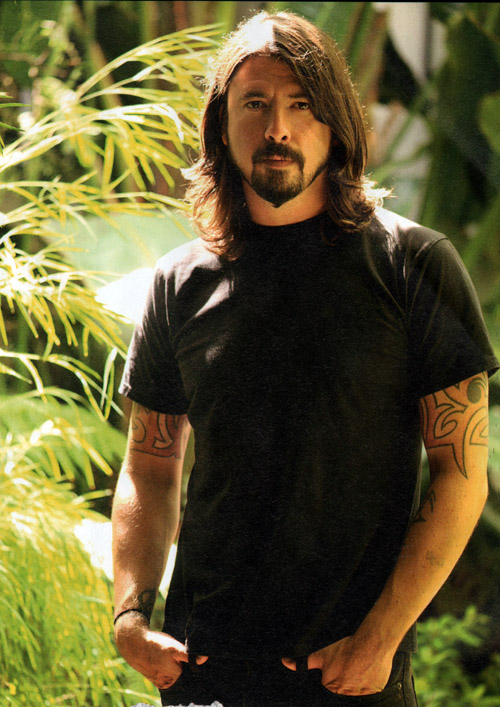

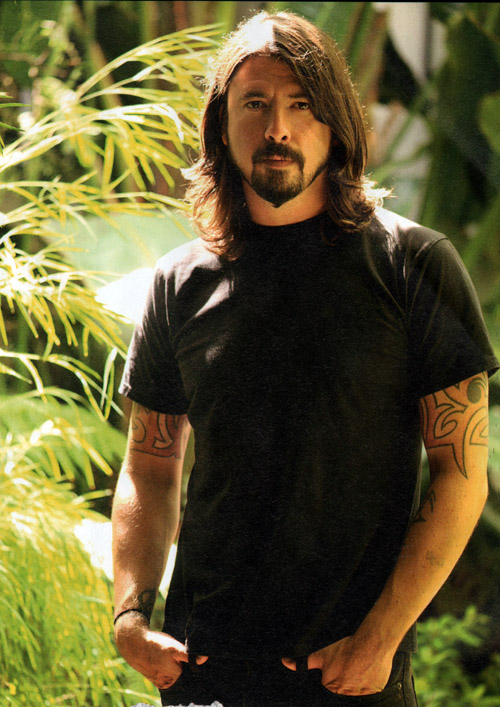

Though he turned 40 in January, there's still something of the excitable teenager about Dave Grohl. That his 40th birthday was celebrated not at a fashionable Los Angeles eaterie, but in Aneheim's branch of the Arthurian-themed Medieval Times restaurant chain, where childhood friends, rock star buddies and family members donned paper crowns before tucking into BBQ ribs and roast chicken, says much about his unpretentious manner and self-deprecating charm.

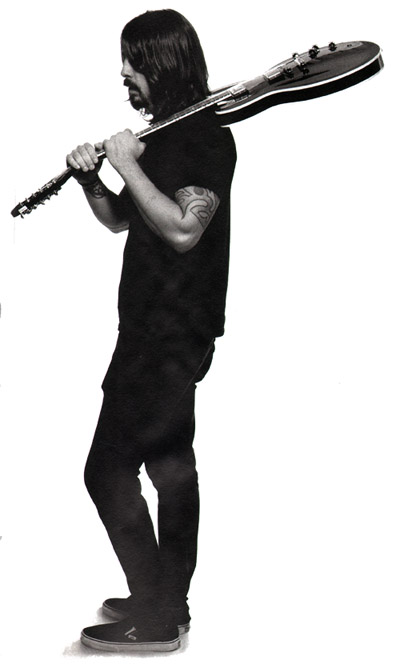

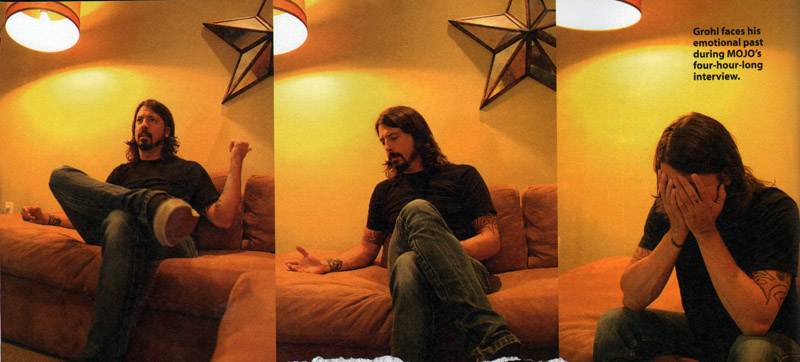

Today Grohl is in rather more upscale surroundings, in a suite at LA's chic Sunset Marquis. California's beautiful people recline in designer swimwear by the pools, Koi carp glide through ponds in the tropical gardens. And, all elongated limbs, gleaming teeth and fading prison-styled tattoos, Grohl sprawls on a couch in his room, laughing off a recent health scare.

"I drank too much coffee and had to go to hospital to get checked out," he explains, flashing his trademark toothy grin. "Man, if I get sent to hospital after drinking coffee, imagine what crack cocaine would do to me. I'd have no teeth and I'd be out sucking dicks in a month..."

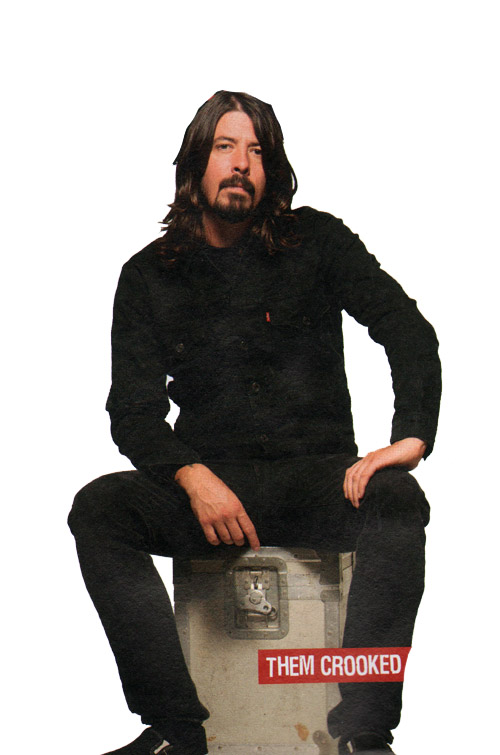

2009 was supposed to be a year off for Grohl, a chance to enjoy proper downtime with his family — expanded, in April with the birth of Harper Willow Grohl, a sister for three-year-old Violet Maye — at the end of a decade during which his band Foo Fighters have quietly established themeselves as one of the world's biggest rock groups. That plan hasn't quite worked out, because since January Grohl has been working with a new project Them Crooked Vultures, a band he willed into existence during a 2005 MOJO interview, when he nominated Queens Of The Stone Age vocalist/guitarist Josh Homme and Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones as two musicians he'd like to collaborate with.

"I wasn't entirely serious, it was more wishful thinking Grohl admits. "But the responsibility of the Foo Fighters can sometimes be overwhelming and so my band all have side-projects — pressure release valves we can hit to keep everyone from losing their mind. And I mentioned it back then because I felt I needed another 'In Case Of Emergency Break Glass' band. And as Josh is my favourite guitarist and John is my favourite bass player I thought it might be fun."

Grohl first met John Paul Jones when the Led Zeppelin man guested on the Foo Fighters' 2005 double album In Your Honour. But he didn't raise the idea of a collaborative project with the bassist until September 2008, on the night he

presented an Outstanding Achievement award to the three surviving Zeppelin members at an awards in London. Four months later, Grohl, Homme and Jones were jamming together in an LA studio.

"It was not unlike a blind date," says Grohl, "where you cross your fingers and hope it's not awkward. Because jamming with the wrong person can be just as awkward as fucking someone you don't like. But it was good and fun and everyone had a smile on their face. We did that for a few days and then looked at one another and said, 'Well, should we be a band?' And that was that."

"It was not unlike a blind date," says Grohl, "where you cross your fingers and hope it's not awkward. Because jamming with the wrong person can be just as awkward as fucking someone you don't like. But it was good and fun and everyone had a smile on their face. We did that for a few days and then looked at one another and said, 'Well, should we be a band?' And that was that."

Unusually in an industry where there are very few genuine secrets, the trio managed to keep details of their new venture under wraps until July. On August 10 they made their global debut at the 1,100 capacity Metro club in Chicago, premiering a hard-driving rock'n'roll sound Homme classifies as "perverted blues". Expectations for their debut LP, released by the time you read this, are high. "Honestly, as a drummer. I can't think of two people I'd rather be in a band with." Grohl insists. "John is a sweet guy, a great player and a brilliant musician. And Josh is like me, a little vandal from the middle of nowhere. He and I have a connection musically that I don't have with anybody else. I had a hunch that the three of us together would make a great band," he grins. "And I was right."

Rewind. It's Summer 1981 And Springfield, Virginia is rocking to a brand new beat. There's a new gang in town, a rock'n'roll outfit caling themselves Nameless. They're wild, they're reckless, they're 12 years old. "We were great," insists former guitarist Dave Grohl. "We'd play backyard parties, do Suffrajette City, Louie Louie, My Generation, classic rock'n'roll. Then the usual problems surfaced: drugs, women, school..."

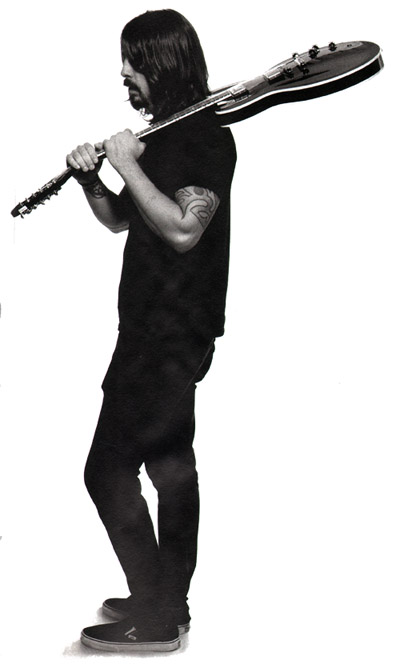

There had always been music in the Grohl household. Dave's father James, a political journalist, was a classically trained flautist, his mother Virginia, a high school English teacher, had performed in singing groups as a teenager. But young Dave's musical education started in earnest when, years after James Grohl walked out on his family, his Mother's new boyfriend, Chip Donaldson, a Vietnam War veteran and English teacher, moved into the family home, filling the house with his extensive classic rock and folk record collection — Dylan, Zeppelin, Jethro Tull, Grateful Dead. Around the same time, Virginia Grohl bought her son a Silvertone guitar and a Beatles songbook. "From then on," says Grohl, "if I wasn't outside looking for crawfish in the creek I was inside learning to play The Beatles."

This innocent adolescent idyll couldn't last forever. And in the Summer of 1983, on a family trip to Evanston, Illinois, Dave Grohl's world was turned on its head by a brash, bratty teenage girl.

Tracey Bradford, 16, was the daughter of Virginia Grohl's best friend and a fully-fledged punk rocker. She had spiked hair, bondage trousers and a collection of hardcore vinyl in her bedroom that set the teenage boy's heart afire. Grohl sat enthralled for 10 straight hours as Bradford dropped the needle on 7-inch after 7-inch, each one harder, faster and wilder than the one before. The music connected instantly with the hyperactive teen and on his return to Virginia 10 days later, Grohl declared himself a punk. Using San Franciscan punk fanzine Maximumrocknroll as his bible, he set out on a quest into the dark heart of US underground rock, seeking out the hardest, heaviest, gnarliest hardcore and thrash metal releases.

"Punk rock and metal is a slippery slope," he laughs. "You start with something like the Ramones and go, Wow, now I want something faster! And then you get to DRI and it's, Wow, I want something noisier! And then you get to Voivod and it's, I want something crazier! And pretty soon you wind up listening to white noise and thinking it's the greatest thing ever!"

Grohl was astonished to discover that some of America's fiercest hardcore bands were from his own backyard, six miles down the 1-95 in Washington DC. Los Angeles may have spawned America's hardcore scene, but it was in DC, through bands such as Minor Threat, SOA and Faith, that hardcore developed a distinct sound, aesthetic and mindset in the '80s, and a code of DIY ethics that would serve as a blueprint for the entire US underground music scene. Grohl dived into the community, travelling to the city each weekend to buy fanzines, trade tapes and check out bands.

"There was always a sense at those shows that anything could happen," he states. "The venues were shitty, the PAs never worked, there were always fights and your new favourite band could sound completely different than they did on the single you'd bought last week. You'd be singing along with one band and 10 minutes later they'd be diving on top of vour head when the next band was on. These people were my musical heroes, but there was no separation between bands and fans."

In summer '84, Grohl joined local punks Freak Baby as guitarist, but switched to drums as the line-up re-emerged as Mission Impossible. Self-taught, he'd learned the basics of drumming by thumping the pillows on his bed while listening to Rush's 2112 album. His raw caveman aggression was soon the talk of the DC scene. "Everyone said, 'You gotta see this drummer, he's 16, he's been playing for two months and he's outta control,'" recalls Ian MacKaye, frontman of Minor Threat and Fugazi, and co-founder of the influential Dischord label. "And when I saw Mission Impossible, Dave was... maniacal. He didn't have all the chops yet, but he wanted to play so hard and so fast, everybody was like, 'Woah, that guy is incredible.'"

A year or two later, as MacKaye was putting together ideas for the band that would become Fugazi, asked Grohl if he fancied coming over to Dischord House to jam. But Grohl had just signed up to play with his favourite band in the world: Scream.

Though Scream were the first band to record a full-length album on Dischord (1983's Still Screaming), Pete Stahl's group were regarded as outsiders on the DC scene: they were from the suburbs (Bailey's Crossroads, Virginia), they

didn't look like a punk rock band, and they'd annoy purist - throwing classic rock hits like Sugarloaf's Green Eyed Lady or Steppenwolf's Magic Carpet Ride into their sets. At one DC show in May 1981, where Scream were billed alongside Minor Threat, and Canada's DOA, almost everyone at the gig walked out when the band began to play. With that kind of hometown reaction, it was little wonder they spent so much time on the road. This suited their new recruit perfectly.

As a kid, Grohl's favourite recurring dream featured him riding a tiny bike along a freeway from his home in Springfield, Virginia to LA. He'd be crawling along at five miles per hour and had thousand miles to go, but he was on the

move, and the feeling of heading out into the unknown was exhilarating. Years later, standing outside DC Space or the Wilson Centre, he would watch jealously as bands packed their gear into vans to drive off to another town and gig.

Before Black Flag there was no grass roots touring in America for punk rock bands. Their pioneering attempts to establish a network of venues, promoters and crash pads nationwide, using phone numbers bassist Chuck Dukowski copied from the sleeves of hardcore 7-inches, was partly born out of necessity - by 1981 the band's hometown shows were notorious for pitched battles between punk kids and the LAPD, making it increasingly difficult for them to get booked anywhere — and partly derived from guitarist Greg Ginn's desire to recreate the chaotic energy of their LA shows in every town and city in America.

"Greg had a ham radio thing as a teenager and through that knew all about fucking up people from other towns — he just extended that to the idea of playing gigs," explains Mike Watt, now with The Stooges, then the bassist with Black Flag's SST labelmates San Pedro agit-funk punks The Minutemen. "Before Black Flag there was no template. The rock'n'rollers really hated punk. so it was hard to play their clubs, so we'd play ethnic halls, gay discos, anywhere that would have us."

"You'd play a lot of crazy shows in those days," laughs former Scream frontman Pete Stahl. "You'd have cops trying to shut down shows, there'd be tension with skinheads — we had a black guy [bassist Skeeter Thompson] in the band, remember — and one night we had a gun pulled on us. But we'd always get by."

In 1986 when Grohl joined Scream it looked like the band were set to transcend their hometown scene. Following the success of 'alternative' rockers U2 and R.E.M., musicians were starting to see a wav out ot the underground: Husker Du had signed to a major label that year and the smart money was on the powerful, passionate Scream to follow suit. But by 1989 it was clear this wasn't going to happen. The band's No More Censorship album had sold 10,000 copies, a decent amount, but less than their label, Ras, had anticipated and they were dropped. Now they had no record deal, no money - and, when they returned from a European tour to discover that Pete Stahl and Skeeter Thompson had been evicted from their shared house, no home either. Another US tour was hastily booked, but as cancellations and problems mounted, Dave Grohl was starting to tire of the struggle.

"Even though I was only 21, I was starting to question this as a decision," Grohl admits. "I was like, Do I really want to be homeless, for the rest of my life? I was tired of having absolutely nothing, I was tired of being hungry, tired of being lost, and tired of being tired... I just wanted to go home."

"Even though I was only 21, I was starting to question this as a decision," Grohl admits. "I was like, Do I really want to be homeless, for the rest of my life? I was tired of having absolutely nothing, I was tired of being hungry, tired of being lost, and tired of being tired... I just wanted to go home."

& When the tour hit LA, Thompson disappeared. It soon became obvious that the bassist wasn't coming back, and his penniless band had no funds to get back home. Stranded and depressed, Grohl saw possibility of at least a few free beers when the band's old friends the Melvins booked an LA show. He called Melvins frontman Buzz Osbourne, and explained the band's plight.

"And Buzz said 'Have you heard of Nirvana? They're looking for a drummer.' So then I had the hardest decision of my entire life," says Grohl. "Do I stay in Los Angeles with my best friends, or do I move on? I remember saying to Franz [Stahl, Scream guitarist] that I was going up to try out for the band, and he just shook his head and said, 'You ain't coming back.' And deep down I knew it too."

January 12, 1992: New York City. Courtney Love wakes up alone in bed in the Omni Hotel. It's 7am, and she's confused, peering into the darkness for her fiance Kurt Cobain. Last night Cobain's band Nirvana were on iconic US TV show Saturday Night Live. Later today they'll receive confirmation that their album Nevermind has knocked Michael Jackson's Dangerous off the top of the Billboard charts. The Seattle three-piece are officially the hottest band in America. But right now Cobain is lying face down on the floor of his hotel room, apparently lifeless. At some point during the night, Nirvana's frontman has shot up heroin and overdosed. Keeping remarkably cool head, Love attempts to resuscitate her lover. - she throws water over the prone body and repeatedly punches Cobain in the stomach until she hears a gasp of breath. Her actions have saved Cobain's life.

Dave Grohl, Cobain's bandmate, will not be told about the incident until he returns home to Seattle.

"There were a lot of those...incidents that you just found out about later," Grohl says slowly. "In a weird way, it just became this... thing that nobody knew what to do about. If you've ever known someone who's battled something like that (huge pause) you just now that there's nothing you can do..."

Cobain was already using heroin when Grohl moved into the singer's apartment at 114 North Pear Street, Olympia in autumn 1990. The drummer, still getting his head around life in a new city with a new room-mate and band, was wholly oblivious.

"I didn't know anything about heroin," he shrugs. :

"I barely knew anything about cocaine. My drug career was limited to heavy hallucinogenics and mountains of weed. I never did coke, I never did heroin, I didn't fucking need speed... and in Virginia, none of us had any fucking money to buy drugs anyway"

Grohl had his own issues to deal with. He felt lost and lonely — "I was up there all by myself with a bunch of strangers who, to be honest, were really weird" — but took comfort in knowing that the new songs the

trio were working on in a barn in Tacoma were shaping up well. At Christmas the drummer returned home to Virginia, and dropped by Dischord House to see Ian MacKaye. He had a rough tape of the new material Nirvana were working on, including a new track titled Smells Like Teen Spirit.

"I said, Wow, that is a fucking good song, this is going to be really popular," recalls MacKaye. "Fugazi had put out Repeater in 1990, and that had sold maybe 250,000 copies, and at the time Nirvana had sold about 40,000 copies of Bleach, so when I said this would be popular I was thinking it could sell maybe 80 to 100,000 records and be a hit among the punk community. It was inconceivable to anyone that this would be a commercial hit."

Nevermind was released in the US on September 24, 1991, debuting at Number 144 in Billboard the following week. Then MTV put the warped high school rally video for Smells Like Teen Spirit on heavy rotation, and the album started leaping up the charts.

"My band Kyuss was on tour," Josh Homme recalls, "and I remember seeing the video at 3am one morning on MTV. I was saying, Man, this is so good, everyone should be into this music but they're not going to be, it's not going to get played because it's too good. And about a week later I realised how wrong I was."

Out on a small US club tour, Nirvana only gradually became aware of the buzz building around the record. "The only indication that our world was turning upside down was when you'd turn up to a 500-capacity club and there'd be an extra 500 people there," says Grohl. "That's when it would be, Holy shit, these people are fucking nuts. But then we went off for the European tour and we were back at the Astoria and a lot of the venues we'd played before, so it didn't seem any different than it ever was. Those two tours were Nirvana playing at our best, we were fucking smoking then and

we had a lot of fun. And then we started to notice there were normal people and jocks at the shows, and it was like, Oh, maybe that video thing is attracting some... riff-raff."

By the time Nirvana appeared on Saturday Night Live, sales of Nevermind had passed the two million sales mark. And for Grohl the descent into "a tornado of insanity" had begun.

"We were still the same people," he sighs, "but everything else around us had changed. I was lucky, I could walk away from each show and disappear. But Kurt didn't have that luxury."

Everyone interviewed for this story who knew Nirvana during their meteoric rise — Ian MacKaye, Josh Homme, Pat Smear and Grohl's long-time friend, producer and drum tech Barrett Jones among them — is at pains to point out that, for the most part, being around the band at this point was a lot of fun, an exciting time for all: "There were definitely some tensions," admits Jones, "but from the inside looking out you don't see all the craziness that the press likes to focus on."

But from the outside looking in, life in Nirvana didn't look like fun at all. The UK inkies were obsessed with the group, with the contradictions inherent in being a hugely successful punk rock band and, in particular, with the Cobain-Love relationship. For at least two years every opinion put forth by grunge's golden (brown) couple was treated with a gravitas that, in hindsight, seems laughable.

"What do you think of when you think of Kurt?" Grohl asks rhetorically. "You think of a rock star that killed himself, because of this guilt of being a rock star. When I think of Kurt, I think of the way he giggled, or how he loved ABBA, or him saying to me, 'God man, I wish I could wear sweatpants.' He was a human being, a nice guy and, maybe it's selective memory, but I don't want to think of him as some brooding, suicidal genius. But I understand that's what legends are made of.

"Reading John Lennon interviews you can see how he was so conflicted, such a tangled ball of contradiction, how he was searching and confused and passionate and a genius," Grohl continues. "And I see a lot of similarities with Kurt. Please don't quote me saying he was a songwriter like Lennon, but there are some similarities in those two personalities that made for some great contradictions and it's really complicated to figure them out. Did Kurt want to be considered the greatest songwriter in the world? I think he did. Was he cool with everything else that came along with that? No. Did it keep him from writing songs? No. At the end of the day, if you don't want to fucking do something, don't do it.

"Reading John Lennon interviews you can see how he was so conflicted, such a tangled ball of contradiction, how he was searching and confused and passionate and a genius," Grohl continues. "And I see a lot of similarities with Kurt. Please don't quote me saying he was a songwriter like Lennon, but there are some similarities in those two personalities that made for some great contradictions and it's really complicated to figure them out. Did Kurt want to be considered the greatest songwriter in the world? I think he did. Was he cool with everything else that came along with that? No. Did it keep him from writing songs? No. At the end of the day, if you don't want to fucking do something, don't do it.

"One of my favourite lines in a Nirvana song — which is fucking dark and which I didn't realise the weight of until I sat in my house in Seattle playing Ian MacKaye the first mixes of in Utero — is the line on Scentless Apprentice where Kurt sings, 'You can't fire me because I quit.' If there's one line in any song that gives me the chills it's that one. Maybe all those things that people wrote about him painted him into a corner that he couldn't get out of."

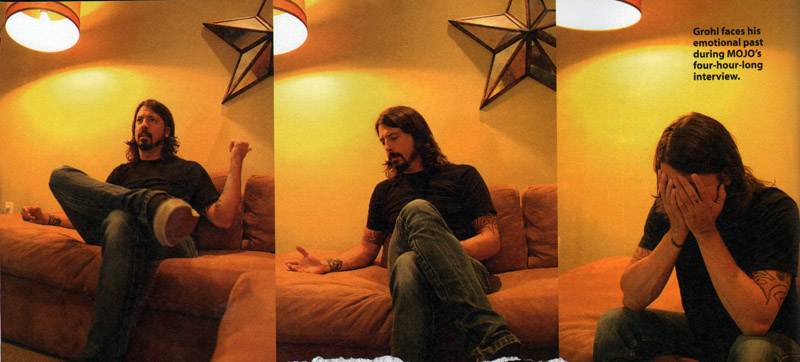

When Grohl talks about Cobain in Nirvana's last year his body language and speech patterns change. The bounce disappears from his voice, and his recollections are delivered haltingly. At one point today he slides down the couch until he's almost horizontal, his head in his hands and tears in his eyes. In typical Grohl style he later laugh this off with a joke — "I can't believe we just had an Oprah moment there" — but it's evident that, all these years later, some memories are still raw.

After In Utero, could you see another Nirvana album coming? "Honestly, no. 1994 was a bad year. That whole year is blurry to me because of how lost I was. By the time we got to Germany on our European tour Kurt didn't want to be there any more. And that tour was the first time I'd ever felt depression, like can't-get-out-of-fucking-bed depression. So then Kurt intentionally blew his voice out so that we could all go home. So finally I get home and collapse and I wake up at 5am to an emergency phone call. 'Dude, turn on CNN...' And I see Kurt, in Rome, so...that's when I knew (whispers) Oh no, it's over..."

It was March 4, 1994, and Cobain was in a coma, after swallowing 60 Rohypnol pills. "So, I see that and I'm like, What the fuck? And then someone called and said that he died, and I lost it. I just fucking lost it. And then someone rings up again and goes, 'Oh, No he didn't die.' It was so crazy and chaotic.

"When Kurt came home, we talked on the phone and I didn't tell him that someone had told me that he'd died, but I told him that I was terrified and so worried. And he was really apologetic, like, 'So sorry, I was partying and drinking and I wasn't paying attention to what I was doing.' I said, Listen, I don't think you should die for this! And then, well, then, you know what happened..."

When the next phone call came, was there any sense that maybe this was another false alarm? "When he actually died? I was totally non-emotional. I don't even know if I was in shock, I was just shut down. I remember trying to make myself cry and I couldn't.

"It's hard for me to even talk about," Grohl admits. "A lot of fucked up shit went down that nobody knows about. I'd had enough before Kurt disappeared, Krist and I had both had enough of it. Maybe at that point it was time for everybody to back away from it. But... that didn't happen of course."

November 2007. Foo Fighters are in Canada, supporting Bob Dylan on the latter's Modern Times tour. Dave Grohl is in his dressing room when he gets a message that Mr Dylan wants to see him.

"So I walk out," says Grohl, "and he's standing like a silhouette in a dark corner — black leather boots, black leather pants, black leather jacket. He said, 'What's that's song you got, the one that goes "The only thing I ever ask of you is you gotta promise not to stop when I say when"?' I said, Oh, yeah, Everlong. He said, 'Man, that is a great song, I should learn that song'." Grohl laughs loudly. "So I don't give a fuck what anybody else thinks," he adds. "Bob Dylan likes one of my songs. That right there is enough for me."

Everlong, arguably the finest song Grohl has written, was penned luring one of the lowest points in his life. It was Christmas 1996. Grohl was newly divorced and homeless, had no access to his own bank account, was sleeping in a sleeping bag on a friend's floor and both his drummer, William Goldsmith, and guitarist, Pat Smear, were on the verge of quitting his band. In the midst of such turmoil, in about 45 minutes, he wrote his most perfect, pure love song.

Grohl had been writing songs for his own amusement since he first began playing guitar back in 1981: his first song, an ode to the family's dog, was titled Bitch. The point was never to impress anyone else, but simply to prove to himself that he could do it.

"I wasn't honestly aiming for anything," he insists. "I would listen back to the songs and I didn't necessarily like the sound of my voice and I certainly didn't consider myself a songwriter, but they were little experiments, little challenges. When I started playing guitar I viewed Beatles records as puzzles, and then later on in life I used them as a sort of template to challenge my self to write the sweetest,

most simple pop song I possibly can. But there'll always be a side of me that loves those big riffs too."

Balancing big rock riffs with pop melodies has been the Foo Fighters' trademark from day one. Famously, the songs that made up the band's self-titled debut album were recorded by Grohl alone (with additional guitar on one track by Afghan Whig Greg Dulli) in just five days, but he had been stockpiling and demoing the tracks for years: all but three were written before Cobain's suicide, and in fact he had played Cobain a demo version of Alone + Easy Target as far back as December 1991.

"Kurt was staying in a hotel in Seattle at the time, as by then he'd moved to LA," Grohl remembers. "I'd told him I was recording and he said, 'Oh, I wanna hear it, bring it by...' He was sitting in the bath-tub with a Walkman on, listening to the song, and when the tape ended he took the headphones off and kissed me and said, 'Oh, finally, now I don't have to be the only songwriter in the band!' I said, No, no, no, I think we're doing just fine with your songs.

"Pat Smear later told me that Kurt loved the [Foo Fighters song] Exhausted too, and he wanted Nirvana to do it, but he didn't

want to ask me if he could change the lyrics. I wish he had because I would have said, 'Absolutely.' To have that beautiful voice over one of my songs would have been amazing. After what happened to Kurt, there was a lot of emphasis placed on the meaning of the first Foo Fighters album," Grohl acknowledges. "But I'd deliberately written nonsensical lyrics: there was too much to say."

To this day Dave Grohl maintains that he initially viewed the first Foo Fighters album as no more significant than the 10 track cassette-only Pocketwatch album he sneaked out on the tiny Simple Machine label in 1992 under the pseudonym Late!, but he admits "when I heard I'll Stick Around for the first time, mixed, I kinda had an anxiety attack because I finally realised this was good. I thought, Oh shit, this is real."

"Dave thought he was just making a demo," laughs Barrett Jones, "but I knew we were making a big album."

Despite the attention news of his return to music was attracting,. Grohl tried to keep the project low key:

after turning Foo Fighters into a full-fledged band with the addition of guitarist Pat Smear, bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith, the band's first US tour was supporting one of Grohl's long-term heroes, Mike Watt, in clubs.

"The main challenge for us was to establish our own identity and not use Dave's past as a crutch," says Mendel. "We were pretty conscious about how we did the band initially — we didn't even put out a video for the first song. We were trying to take it back a step to a couple of years before Nirvana blew up and do what we were all comfortable with. But Dave had an amazing amount of enthusiasm and a great attitude about what this band could be. We approached everything with the idea that we'd make every show and everything we do an exciting adventure."

Foo Fighters' early years were not problem-free. Goldsmith left the band during the recording of 1997's The Colour And The Shape, Smear departed soon afterwards, citing exhaustion, and his replacement, Grohl's old friend from Scream Franz Stahl, was let go when it became apparent that he wasn't jelling with Grohl, Mendel and new drummer Taylor Hawkins. But their career trajectory seemed unstoppable. The Colour And The Shape notched up two million US sales, its follow-up, 1999's There Is Nothing Left To Lose, landed the band's first Grammy. Grohl's songwriting was becoming increasingly sophisticated, too, as he gained the confidence to start incorporating influences from Tom Petty and The Beatles, though his lyrics remained deliberately vague.

"I don't see what's wrong with someone not knowing the specific inspirations to a song," he maintains. "There's a wonderful part of songwriting that perhaps everyone could relate to a lyric for their own reason, so that when we go out and play,' say, Best Of You for 80,000 people maybe they're singing along for 80,000 different reasons. Because you know

what, you're gonna sing a song a lot fucking louder for your reasons than for mine. And, after the Nirvana thing exploded it definitely changed the way I relate to people — fuck yeah, I wanted to keep a lot of me for me.

"It might have something to do with growing up in such a small family," he muses. "There was my Mom, my Dad, my Sister and I, and I had two best friends and that's all I fucking needed. I don't consider myself a loner, but, it's just not important to me to be everyone's best friend. Maybe it's a defence mechanism, but I already get to hang out with my best friends Taylor, Nate, Chris and Pat for a living."

That friendship between Grohl and his bandmates came under the most strain in 2001 during the troubled birth of the Foo Fighters' fourth album, One By One. As with There Is Nothing Left To Lose, sessions began in Grohl's basement studio in Virginia, but ideas weren't flowing as easily as in the past. A time-out was called in August to allow the band to visit the UK to play the V Festival, but while in London Taylor Hawkins accidentally overdosed on painkillers and slipped into a two day coma.

"That changed everything," says Grohl. "It was the first time in my life that I ever considered quitting music, because I was wondering if music just equalled death. Because I didn't want to do it if everyone is just gonna die all the time. I would walk from that hospital back to my hotel every night and talk to God, out loud, as I was walking. I'm not a religious person, but I was out of my mind, I was so frightened, and heart-broken and confused. And I said to everyone, I don't even wanna hear the word 'Foo Fighters' until I'm ready to say it again."

"That changed everything," says Grohl. "It was the first time in my life that I ever considered quitting music, because I was wondering if music just equalled death. Because I didn't want to do it if everyone is just gonna die all the time. I would walk from that hospital back to my hotel every night and talk to God, out loud, as I was walking. I'm not a religious person, but I was out of my mind, I was so frightened, and heart-broken and confused. And I said to everyone, I don't even wanna hear the word 'Foo Fighters' until I'm ready to say it again."

In retrospect, Hawkins and Grohl both concede that the band rushed back into action too quickly following what the

band euphemistically refer to as "Taylor's nap". The recording sessions were shifted from Virginia to LA's Conway Studios, steeply accelerating costs, but doing nothing to stimulate creativity. At the same time Grohl, who had already recorded the drums for Queens Of The Stone Age's Songs For The Deaf album, was rehearsing with that band for a one-off show at LA's Troubadour, and becoming increasingly aware of the marked differences in the intensity of those sessions relative to the tepid mood at Conway Studios.

"At night I'd go rehearse in a closet with Queens and be totally energised, and then come to the studio and be totally dismayed by the apathy," Grohl recalls. "So things started getting tense. We were finishing the original version of the album and Kerrang! was there doing a cover feature and I remember getting into a fight in the control room while the journalist and photographer were outside. People were making little jabs and comments and I said, OK, do you want me to go out and tell those guys we're gonna break up right fucking now? Because we can if you want..."

QOTSA frontman Josh Homme was more than aware of the friction Grohl's decision to play with his band was having in the Foos camp. "Absolutely," he admits. "Band people, and I mean this in a very blanket way, are very easily rattled, because many bands don't last and they're such an unpredictable animal that it's easy to get your confidence rattled. But I always knew that Dave was going to go back to Foo Fighters: I was always trying to intimate that this wasn't something the other guys needed to worry about, but that's kinda impossible because sometimes people can hear those words and think they're being stitched up."

On March 7, 2002, Grohl played the Troubadour with Queens. It was a big deal for him, his first proper drumming gig since Nirvana, and he invited all his closest friends along. There was one conspicuous absentee however: Taylor Hawkins.

"That really hurt me," Grohl admits. "Taylor was mv best friend. It was like him not turning up for my wedding."

"It's funny we've never discussed this," says Hawkins. "Dave's never even said anything about this to me. But to me, going to see Dave play with Queens would have been like going to see your girlfriend fuck some other dude. I know he wasn't trying to hurt me, but our band was falling apart: it was a tough time and it felt a little hurtful to me too. Because to me that spelled out the end of our band."

With the album deadlines looming and management already putting together a promo schedule for the band, Dave Grohl came to the realisation that he really didn't like this new album at all. Thus in April he called a band meeting, announcing to his shocked bandmates that he was scrapping the album — writing off one million dollars in studio costs in the process — and furthermore was going to take time out to drum for Queens Of The Stone Age on tour.

Foo Fighters still, however, had live commitments to honour, not least a main-stage performance at the Coachella festival. But with morale in the camp at an all-time low, rehearsals were fraught and awkward. Perhaps consequently, a disagreement over the setlist soon escalated into a finger-pointing, screaming argument.

"I thought, OK, I think this is going be the last show, but I didn't say anything," admits Grohl. "But the vibe was so bad."

"I thought, OK, I think this is going be the last show, but I didn't say anything," admits Grohl. "But the vibe was so bad."

"That argument actually helped clear the air and save the band," says Taylor Hawkins, who now admits he was being an "asshole" to Grohl at the time. "That was when Dave let everyone know, 'I'm leading this band.' It was, 'Don't question me, everyone can have their opinion, but I'm the leader, I'm gonna have the final word, I'm gonna make the decisions and I'm gonna essentially write the songs.' And everyone went, 'OK, well, now I understand where we're at.' The dynamic changed a little bit, but in a way it made things easier."

Grohl spent summer 2002 on the festival circuit with Queens Of The Stone Age. He found the whole experience liberating, empowering and hugely motivating.

"I think it was the first time I've ever felt truly confident and strong in a band," he reflects. "Walking through the backstage area of a festival with Queens is like the moment in a Western where the saloon bar doors swing open and the piano player stops playing and everyone just stares.

"You have Josh, [Mark] Lanegan. [Nick] Oliveri and me walking in a straight line and it's like being in the coolest gang. We never had a bad show, and every show just got better and better.

"But I started to miss my friends. The Foo Fighters had become a family and I'd been away from home for too long..."

"What was great about that time," says Josh Homme, "was that Dave did go back. And that said that it's possible to have a musical mistress. It would have been terrible if Dave had stayed in Queens because it would have killed the suggestion that you can do multiple things. It was a rare moment which proves that having multiple personalities isn't a bad thing for someone playing music. Because once you feel you can do anything in music, that's when you can get closer to God."

October 14, 2009. It's the ninth date of Them Crooked Vultures' first-ever US tour and Dave Grohl is back on home soil, for a sold-out show at Washington DC's 9:30 Club. Almost inevitably his thoughts are on the musical journey he has undertaken since first leaving these streets behind as a 17-year-old high school drop-out. The kid who started playing music by learning Beatles songs in his bedroom now has Paul McCartney's phone number in his Blackberry and considers him a friend: "He's the sweetest guy," says Grohl. "I love him to death." And as 2009 draws to a close there are three separate chapters of Grohl's life on the shelves of record shops worldwide - the DVD of Nirvana's classic 1992 Reading festival headline show, the Foo Fighters expansive' Greatest Hits collection and Them Crooked Vultures' debut album: if ever this most unassuming rock star could be forgiven a satisfied smile, this would be it.

"I'm proud of a lot of the shit I've done," Grohl admits. "I feel blessed that I've got to experience all these things, and accomplish so much. And do I think it's luck? No. Do I work hard? Yes. Am I fucking good at what I do? I think so. But am I going to tell everybody in the world that I think I'm a great songwriter and amazing drummer and huge rock star? No, that's not my fucking style. "It still amazes me that we've taken this thing from a fucking demo cassette made in five days to selling out two nights at Wembley Stadium. You get there and it would be very easy to say, All right, let's pack it up, we don't need to do anything else, what more can we possibly accomplish? I really can't imagine where we go from here, man I never thought any of this was possible.

"But, you know, I remember that certain people really resented me for having the audacity or gall to keep playing music after Nirvana, and at the time that, to me, was the most ridiculous thing. I wasn't finished. And you know what, I'm still not finished."

LEARNING TO FLY

How Tom Petty helped Dave Grohl crawl out from the wreckage of Nirvana...

October, 1994. Some six dark months after Kurt Cobain's death, Dave Grohl booked time at Robert Lang Studios in Seattle to begin recording some solo material. Grohl, however, was unsure of where his future truly lay. Then came a call from Tom Petty, a man that Grohl deeply admired, and who coincidentally had just parted company with the Heartbreakers'volatile drummer Stan Lynch.

"Right when the thing with Stan Lynch happened, we were already booked to go on Saturday Night Live so that left us high and dry," explains Petty. "So we thought, first of all, who's a great drummer? Dave Grohl is our favourite drummer right now and he isn't doing anything. So I called Dave's office. He phoned back and was really keen to do it."

Grohl's appearance with the Heartbreakers on Saturday Night Live aired on November 19, 1994, and, though typically unheralded at the time, marked the man's first public performance since Cobain's death.

"I didn't get that deep with him about Kurt Cobain," recalls Petty today. "What I did talk to him about was joining the Heartbreakers. He thought about it but he was torn. He told me he'd just completed [what became] the first Foo Fighters album on which he'd played everything, so the idea of actually being in a band really appealed to him. But I told him that with that going on, and with a deal, he would be unhappy with us. We're an older bunch of guys and I thought he would be happier doing his own thing."

Petty's honesty provided Grohl with a further spur to fine-tune the album he'd been working on, forming the Foo Fighters proper and embarking on a career that has long-since outlasted Nirvana's.

Some 15 years on, Petty remains a firm friend and fan of Grohl's. "He's become his own force of nature with his band," smiles Petty. "He's got tremendous energy and a lot of power, and he sings with a lot of power. He's a musician who came up playing live and you can tell that he really knows his chops."

Words: Paul Brannigan Photos: Ross Halfin

back to the features index

"It was not unlike a blind date," says Grohl, "where you cross your fingers and hope it's not awkward. Because jamming with the wrong person can be just as awkward as fucking someone you don't like. But it was good and fun and everyone had a smile on their face. We did that for a few days and then looked at one another and said, 'Well, should we be a band?' And that was that."

"It was not unlike a blind date," says Grohl, "where you cross your fingers and hope it's not awkward. Because jamming with the wrong person can be just as awkward as fucking someone you don't like. But it was good and fun and everyone had a smile on their face. We did that for a few days and then looked at one another and said, 'Well, should we be a band?' And that was that." Saturday, July 3, 1983. It's a beautiful day in Washington DC and tens of thousands of American citizens are descending upon the Nation's capital for the annual Independence Day fireworks display on the Mall. But one local teenager has other plans. Fourteen-year-old Dave Grohl is bound for the Lincoln Memorial, in whose shadow 20 hardcore punk bands, among them Dead Kennedys, Reagan Youth, DRI and MDC (aka Millions Of Dead Cops) are due to play a free Rock Against Reagan gig.

Saturday, July 3, 1983. It's a beautiful day in Washington DC and tens of thousands of American citizens are descending upon the Nation's capital for the annual Independence Day fireworks display on the Mall. But one local teenager has other plans. Fourteen-year-old Dave Grohl is bound for the Lincoln Memorial, in whose shadow 20 hardcore punk bands, among them Dead Kennedys, Reagan Youth, DRI and MDC (aka Millions Of Dead Cops) are due to play a free Rock Against Reagan gig. "Even though I was only 21, I was starting to question this as a decision," Grohl admits. "I was like, Do I really want to be homeless, for the rest of my life? I was tired of having absolutely nothing, I was tired of being hungry, tired of being lost, and tired of being tired... I just wanted to go home."

"Even though I was only 21, I was starting to question this as a decision," Grohl admits. "I was like, Do I really want to be homeless, for the rest of my life? I was tired of having absolutely nothing, I was tired of being hungry, tired of being lost, and tired of being tired... I just wanted to go home." "Reading John Lennon interviews you can see how he was so conflicted, such a tangled ball of contradiction, how he was searching and confused and passionate and a genius," Grohl continues. "And I see a lot of similarities with Kurt. Please don't quote me saying he was a songwriter like Lennon, but there are some similarities in those two personalities that made for some great contradictions and it's really complicated to figure them out. Did Kurt want to be considered the greatest songwriter in the world? I think he did. Was he cool with everything else that came along with that? No. Did it keep him from writing songs? No. At the end of the day, if you don't want to fucking do something, don't do it.

"Reading John Lennon interviews you can see how he was so conflicted, such a tangled ball of contradiction, how he was searching and confused and passionate and a genius," Grohl continues. "And I see a lot of similarities with Kurt. Please don't quote me saying he was a songwriter like Lennon, but there are some similarities in those two personalities that made for some great contradictions and it's really complicated to figure them out. Did Kurt want to be considered the greatest songwriter in the world? I think he did. Was he cool with everything else that came along with that? No. Did it keep him from writing songs? No. At the end of the day, if you don't want to fucking do something, don't do it. "That changed everything," says Grohl. "It was the first time in my life that I ever considered quitting music, because I was wondering if music just equalled death. Because I didn't want to do it if everyone is just gonna die all the time. I would walk from that hospital back to my hotel every night and talk to God, out loud, as I was walking. I'm not a religious person, but I was out of my mind, I was so frightened, and heart-broken and confused. And I said to everyone, I don't even wanna hear the word 'Foo Fighters' until I'm ready to say it again."

"That changed everything," says Grohl. "It was the first time in my life that I ever considered quitting music, because I was wondering if music just equalled death. Because I didn't want to do it if everyone is just gonna die all the time. I would walk from that hospital back to my hotel every night and talk to God, out loud, as I was walking. I'm not a religious person, but I was out of my mind, I was so frightened, and heart-broken and confused. And I said to everyone, I don't even wanna hear the word 'Foo Fighters' until I'm ready to say it again." "I thought, OK, I think this is going be the last show, but I didn't say anything," admits Grohl. "But the vibe was so bad."

"I thought, OK, I think this is going be the last show, but I didn't say anything," admits Grohl. "But the vibe was so bad."