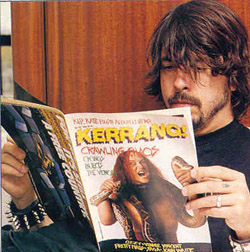

Kerrang! 2003

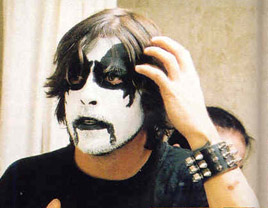

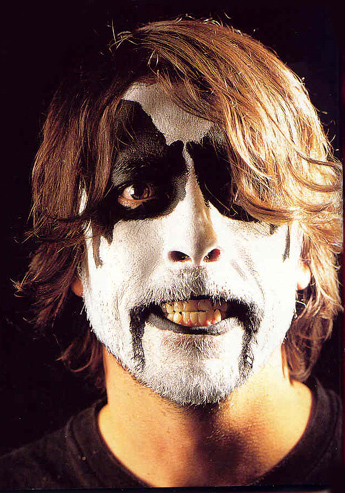

Dave Grohl has talked about making a balls-out heavy metal album for years. Now that he's finally done it with Probot, you might never think of the Foo Fighters mainman in the same way again....

Kerrang! 2003

Dave Grohl has talked about making a balls-out heavy metal album for years. Now that he's finally done it with Probot, you might never think of the Foo Fighters mainman in the same way again....

"I'm not sure about this," he thought. "I'm not sure about this at all."

"I'm not sure about this," he thought. "I'm not sure about this at all." It may have been all about personality, his personality, which seemed to transcend and translate no matter what the setting. Or it may have been down to the quality of the music, 'Monkey Wrench' for one, laying down a more than passable floor beat for a festival circle-pit. But then it might have been something else, something to do with a chiming integrity and a shared musical understanding. An affinity, if you like. As the crowd at the National Bowlcheered with welcome and acceptance, Dave Grohl looked to the wings of the stage. There he saw people such as Phil Anselmo from Pantera and Anthrax's Scott Ian singin along to his songs. To his suprise, to his amazement, he saw people from groups whose music he loved singing every word to songs he presumed they would hate.

It may have been all about personality, his personality, which seemed to transcend and translate no matter what the setting. Or it may have been down to the quality of the music, 'Monkey Wrench' for one, laying down a more than passable floor beat for a festival circle-pit. But then it might have been something else, something to do with a chiming integrity and a shared musical understanding. An affinity, if you like. As the crowd at the National Bowlcheered with welcome and acceptance, Dave Grohl looked to the wings of the stage. There he saw people such as Phil Anselmo from Pantera and Anthrax's Scott Ian singin along to his songs. To his suprise, to his amazement, he saw people from groups whose music he loved singing every word to songs he presumed they would hate.

For the past month Dave Grohl has been explaining to people, to journalists, the point of his one time, metal-schooled, multi-personnel project, Probot. Some of them 'get' the music, some the idea, some the music and the idea, and some get fuck all. Last year when Grohl was touring with QOTSA in th US he was approached by a woman who looked to be nearing 50 years of age, a woman who wanted to know when the Probot album was coming out. At that time he didn't know, and tried to  explain to the lady that, anyway, she might not like it, that it "might not be her thing". And now he's wondering. Because people who believe themselves to understand music, some of them anyway, have been questioning Dave Grohl about this thing he's done, this thing that is so alien, so foreign and so removed from the melody and warmth of the Foo Fighters. People who only hear a sound, without seeing anything that may have informed it, or it's main creator.

explain to the lady that, anyway, she might not like it, that it "might not be her thing". And now he's wondering. Because people who believe themselves to understand music, some of them anyway, have been questioning Dave Grohl about this thing he's done, this thing that is so alien, so foreign and so removed from the melody and warmth of the Foo Fighters. People who only hear a sound, without seeing anything that may have informed it, or it's main creator.

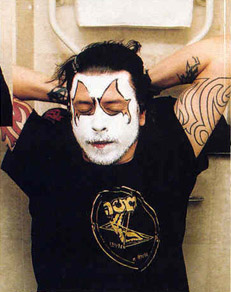

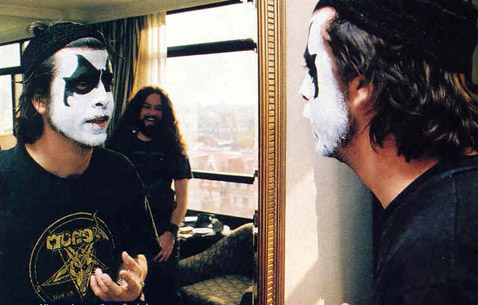

He's been patiently - for Dave Grohl is nothing if not patient, at least with others - explaining that to him "Nirvana were not just a punk band" in much the same way "Motorhead were not just a metal band". He'll explain that when he heard Metallica's 'Kill 'Em All' in '83 that, for him, it was "fucking exciting", that it was "fucking great". He'll speak of a Xeroxed fanzine catalouge called 'Over The Rainbow' that featured merchandise and records from all of the bands he'd never heard of, 'thrash' bands such as Venom and Exodus and Possessed, Dark Angel and Celtic Frost. He'll say that he and his friends from Virgina would go see, say, Voivoid on one weekend and Bad Brains the next, and that they'd see exactly the same faces in the crowd. Because what Dave Grohl is trying to explain is that the punk scene in which he originally found shelter - with it's tradition of tape trading, underground concerts and tours in vand that ran like milkfloats - is no different whatsoever from the underground metal scene which bled into him just a short time later. Perhaps he might even be sugesting that while mainstream seems to be his sound - "that is a thorn in my side," he'll say, "the fact that everything I do seems to have this sense of melody in it" - the mainstream itself is not his instinct. And while people seem to have no trouble understanding, and accepting, the punk credentials - Scream first, the Nirvana, no problems there - the metal sound of his project really throws them the loop. Never mind. There's a chill autumn blow ruching through the finery of Knightsbridge, Wst London. But inside the not quite stifilingly exclusive Millenium Hotel there is all the warmth of Dave Grohl's smile, a smile wide enough to use as a hammock and bright enough that the dental work might well glow wild under ultraviolet light. A black suited, red shirted, black skinned pianist is playing the blues on the bar's grand piano. Dave Grohl in t-shirt and jeans, tattoos running down from his sleeves, sits in the corner of the room, sipping a soft drink and smoking light cigarettes. A set of friends and colleagues lounge at neighbouring tables, a collection of peircings and washed and uncut hair, wearing t-shirts that boast the legends of bands such as Venom and Bathory, from an age before metal went money.

Never mind. There's a chill autumn blow ruching through the finery of Knightsbridge, Wst London. But inside the not quite stifilingly exclusive Millenium Hotel there is all the warmth of Dave Grohl's smile, a smile wide enough to use as a hammock and bright enough that the dental work might well glow wild under ultraviolet light. A black suited, red shirted, black skinned pianist is playing the blues on the bar's grand piano. Dave Grohl in t-shirt and jeans, tattoos running down from his sleeves, sits in the corner of the room, sipping a soft drink and smoking light cigarettes. A set of friends and colleagues lounge at neighbouring tables, a collection of peircings and washed and uncut hair, wearing t-shirts that boast the legends of bands such as Venom and Bathory, from an age before metal went money.

Grohl is explaining how Probot, really, came from nothing, or at least nothing other than his fear, following the recording of tho melodious 'There Is Nothing Left To Lose' in 1999, that he might be losing touch with the sound of the underground. So he wrote a few riffs, hurried downstairs to the studio in the basement of his Virginia home and played and then embellished these guitar riffs with bass and drums. Within three days he had half an album's worth of material. Two years later - a couple more riffs, three days recording - he had a full record. The instrumental form of this music, he says he gave the many vocalists who came to feature on the record - Lemmy, Lee Dorian (Cathedral), Wino (Spirit Caravan), Cronos (Venom), Eric Wagner (Trouble) among others -the freedom to do their own work. And he had the confidence to trust theirstuff. Right enough, because no-one let him down. Each and every performance within, Dave Grohl says, "surprised me, each vocalist brought something to their song that I could never have imagined".

Lee Dorian, a man so metal he has to stay indoors during lightning storms, is sitting alongside Grohl, smoking a cigar. Dorian renrded his vocal part on a DAT tape in a frinnd's bedroom. The Englishman says that the Probot record is "the best metal record I've heard all year".

When he says this Dave Grohl looks over and appears genuinely, quietly and deeply touched.

"When I started recording this stuff, and it was four years ago remember. I didn't for a moment imagine that it

would become a record." he says. "I just wanted to record something for fun. But then it started to turn into something, and I decided to speak to people to take it futher. But t was so nervous about contacting some of these guys.

Wino is a God to me as is Eric Wagner. If I could only ever hear one metal album again then it would be Trouble's 'Psalm 9'. And here I was calling up Eric Wagner in Chicago and saying, 'Hi I'm Dave from the Foo Fighters - would you like to sing on

a metal song that I've written?'. What the fuck was he likely to say to that? But it turned out that he was excited

by it, it turns out that everyone was excited by it.

And you?

"I can't tell you how much it means to have the luxury of this opportunity. Not only of Probot, but all the opportunities that success allows me. Its important to extend yourself to other types of music, to other types of people.

It's good for your fucking soul, for your fucking heart."

At the time that the teenage Dave Grohl was discovering his metal edge, in the United Kingdom there raged a

civil war, and thee setting for this civil war lay right here in the pages of this magazine. This thing called 'thrash

metal' had come screaming over the horizon, a thing so terrifying even regular heavy metal fans - at the time

much more ostracised, patronised and insulted than today - were frightened by it. And this noise became the victim's

victim, hated and mocked; only, thrash metal was far too thuggish - perhaps eVen a littie too ignorant - to bother

itself with that. It had no sense of melody, no sense of fun, not much sense at all, actually. At its best it merged the

fury and refusal of punk with the relentlessness and isolation of metal. It reached its peak - and really, fell stone

flat dead from thereon in - quickly when in '86 Slayer capped the creative summit in the 28 minutes of pitch

black murder known as 'Reign In Blood'. But as late as the end of this decade thrash metal was topping the chart in

the 'Shittiest Thing' section of the Kerrang! end of year poll. And all the while Motley Crue and Poison stood tousled and triumphant, appearing to rule the world.

At the time that the teenage Dave Grohl was discovering his metal edge, in the United Kingdom there raged a

civil war, and thee setting for this civil war lay right here in the pages of this magazine. This thing called 'thrash

metal' had come screaming over the horizon, a thing so terrifying even regular heavy metal fans - at the time

much more ostracised, patronised and insulted than today - were frightened by it. And this noise became the victim's

victim, hated and mocked; only, thrash metal was far too thuggish - perhaps eVen a littie too ignorant - to bother

itself with that. It had no sense of melody, no sense of fun, not much sense at all, actually. At its best it merged the

fury and refusal of punk with the relentlessness and isolation of metal. It reached its peak - and really, fell stone

flat dead from thereon in - quickly when in '86 Slayer capped the creative summit in the 28 minutes of pitch

black murder known as 'Reign In Blood'. But as late as the end of this decade thrash metal was topping the chart in

the 'Shittiest Thing' section of the Kerrang! end of year poll. And all the while Motley Crue and Poison stood tousled and triumphant, appearing to rule the world.

Only they didn't rule the world, and the civil war they lost. These bands. And most of their type, are now dead.

Over seven hard years - with a fatal assault finally coming with 'The Black Album' - Metallica ripped the life from these creatures. And in seven exhilirating months Nirvana stopped by in their pick-up truck and drove forwards and backwards over their heads just to make sure.

And if The Darkness represent an awful invitation back to the days of poseurs and pout then

Probot recalls a time when it waS possible to get angry, if not laid.

"Those bands were something neither me or my friends

had anything to do with," says Grohl "For one thing they weren't any good. I never listened to the radio when I

was young because I didn't like the music that Was played on it, even on rock radio - especially on rock radio. And I

never watched MTV because you'd never see anything on there that was any good. It was Metallica that opened the

doors for me, to bands like Possessed and Exodus. And it was a very grass roots thing, it was tape trading and digging and searching around for music in the underground. It was about community, about not having it handed to you on a plate. I didn't want it and I didn't want it comfortable. I didn't see the point in liking music that you were supposed to like and that it was safe to like."

When you were in Nirvana you were seen, at least at the time, by many as not so much an alternative to metal but an actual opposition to it How did you feel abold that?

"Well, in Nirvana we never made it our mission to be the poster boys of the alternative revolution or to make it our priority to destroy heavy metal," he says. "That was never something we were really concerned with. And I think the music that died when Nirvana became popular did prove itself to be unimportant, whereas bands like

Slayer and Voivod continued to exist. Because they came from a scene not unlike the underground punk scene, which is why it survived, just as the punk scene survived. It was built from something that mattered.

It was built from something that mattered.

But when you're talking about bands like Winger and Warrant, well that just wasn't part of our world. It was too ridiculous to consider a realilty, which is why it died. And I'm glad that it died. It stopped meaning something to people. But I think that's why people looked to Nirvana, because they thought we were human beings, that we were real people. And it was the time for that."

Following the Foo Fighters' set at the Ozzfest at Milton Keynes. Dave Grohl got into conversation with Anthrax's Scott Ian. Despite their (much) more traditional leanings today, at their creative peak Anthrax and Ian were perhaps more responsible than any band for the cross pollination of metal, not least when they recorded 'Bring The Noise' with NYC rap kings Public Enemy, Scott Ian knew metal, he knew punk, knew hardcore, and rap. And in a way that appears far more

daring than it did at the time; he and his band parading these influences with pride. It's a shame, Grohl and Ian

agreed, that there has to be so much division in music, so many barriers between the bands. between

what you can like and what you can't, or you're not supposed to, like.

Following the Foo Fighters' set at the Ozzfest at Milton Keynes. Dave Grohl got into conversation with Anthrax's Scott Ian. Despite their (much) more traditional leanings today, at their creative peak Anthrax and Ian were perhaps more responsible than any band for the cross pollination of metal, not least when they recorded 'Bring The Noise' with NYC rap kings Public Enemy, Scott Ian knew metal, he knew punk, knew hardcore, and rap. And in a way that appears far more

daring than it did at the time; he and his band parading these influences with pride. It's a shame, Grohl and Ian

agreed, that there has to be so much division in music, so many barriers between the bands. between

what you can like and what you can't, or you're not supposed to, like.

"Because it's really about rock music and non rock music," says Grohl. "Or it's about good music and bad music. If you get a lot of musicians in a room together then it doesn't matter what music they play, because everybody, will usually get along. It's that sense of community that I've always loved."

Which, you suppose, is what Dave Grohl has got with Probot, with all these people, these influences, these friends. But he's got something else too: a statement of intent. Because intergration is one thing, but let's not count out disintergration too quickly, shall we?

Because if conversations regarding togetherness represent the ideal of Probot, then recollections such as this surely do, too. The young Dave Grohl attended a Slayer concert during the 'Reign In Pain' tour of '86. The Californians were appearing in Washington DC, unfathomably at it's gorgeous old hall called the Warner Theater. Unfathomably because Slayer fans, at the time, were like Milwall fans who happened to have been raised by jackals, so the second the houselights died on the evening's . performance trouble descended. As the ridiculous upside down crosses that were part of Slayer's stage-show at the time began to pulse in introduction, so too did the omious tom tom entrance of 'Raining Blood'. And at this, the crowd rushed toward the stage tearing up eight full rows of velvet cushioned, wooden framed, 200-year-old hand-made seats, tossing them loose and smashing them away. Ruined and gone.

And as Dave Grahl recounts this slory he seems, despite himself, thrilled and delighled at the memory of this event. As if he knows, understands, that true metal is about two things: comradeship for sure, but chaos for certain.

Words: Ian Winwood