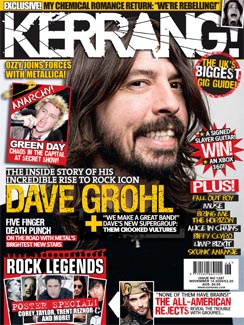

Kerrang!

Dave Grohl's journey to superstardom has been one that rock legends are made of. Kerrang! charts his unstoppable rise...

Kerrang!

Dave Grohl's journey to superstardom has been one that rock legends are made of. Kerrang! charts his unstoppable rise...

David Eric Grohl was born in Ohio on January 14, 1969, to musical parents, journalist James and teacher Virginia. His father

was a flautist, his mother a former singer in a band, but it wasn't until Dave was 10 that he picked up his first guitar and

knocked out the chords to Deep Purple's Smoke On The Water.

"There was always a guitar sitting around our house when I was young: my father was a classically trained musician, but my mother bought him a nylon string Flamenco-type guitar when I was three or four, which he never learned to play, so it just sat around the house," Dave tells Kerrang!. "By the time I was nine, I'd broken four of the six strings on it, but I'd

learned how to play Smoke On The Water on the remaining two strings... Very Beavis and Butthead!"

Soon he took formal guitar lessons, jamming with school friend Larry Hinkle on a '60s Silvertone guitar, complete with

built-in amp. It wasn't a guitar that would last long, smashed during a fit of hyperactivity. It would be replaced with a Les Paul replica with which the young Dave would entertain the folks at the local old people's home during his first ever gig.

At first, he was listening to classic rock, the Rolling Stones, The Who and Led Zeppelin.

"A big rock 'n' roll moment for me was going to see [the 1980 film] ACDC's Let There Be Rock," he remembers today. "That was

the first time I heard music that made me want to break shit! There was me and my friend Larry and two people smoking weed in the back. After the first number in that movie, that was maybe the first moment where I really felt like a punk - I just

wanted to tear that movie theatre to shreds. I still loved the melodies in my rock 'n' roll records, but that sent me on a

mission to find music that wasn't... normal."

And it was a visit to his older cousin Tracey's house in 1982 that alerted him to the growing hardcore scene in Washington DC, near to where his family had moved.

"I was greeted at the door by Tracey," he revealed in 1995. "But it wasn't the Tracey I had grown to love; this was punk Tracey, complete with bondage pants, spiked hair, the whole nine yards. It was the most awesome fucking thing I had ever seen."

She took him to see his first show, the hardcore band Naked Raygun, who had a mind-altering effect on Dave: "I had learned my three basic chords, but after hearing punk rock, I realised you don't have to be Eddie Van Halen to be in a band. You can pick up a guitar and with those three chords [you can] write a song."

Dave soon made himself a local in the DC hardcore scene, meeting fellow teen punk Brian Samuels at a Void show, who recruited

the nascent guitar player for his band Freak Baby. After learning drums at Thomas Jefferson High, he switched to the kit and

the band changed their name to Mission Impossible. "I hadn't the slightest idea how to set the fucking [drum kit] up, but I

sure loved beating the shit out of it. It was 1985 and I was living my hardcore dream!"

"He was pretty young and the stuff he was playing was simple, but he did it with so much power and precision," Dante

Ferrando, the drummer of another DC band. Iron Cross, remembers. "Someone told me he had been playing eight months. I'd been

playing for years and couldn't play like that."

Mission Impossible fell apart when two of its members left for college, but Dave's education continued in hardcore bands. He formed Dain Bramage, with a more experimental and song-orientated bent than the straight-ahead hardcore of Mission Impossible. "That band was really where I started to utilise my growing interest in songwriting: arrangement, dynamics,

different tunings," says Dave.

The band released the album I Scream Not Coming Down in June 1986 but, by the following year, they had split, allowing the drummer to audition for local legends Scream.

"Scream's first two records were among my all-time favourites," he said of his trial. "Originally I'd wanted to call

Franz [Stahl, Scream's guitarist], to see if I could jam with them once or twice, so then I'd be able to tell my friends I

jammed with Scream!"

At 17, he lied about his age to the band and, after being thrown out of school, he'd spend the next four years of his life on tour with his favourite band.

My first trip to Europe was amazing," says Dave, looking back. "In February '88 [Scream] flew into Amsterdam and spent the

next two months playing in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia, England and Spain. Most shows were in squats and youth centres. It was awesome."

Scream toured the U.S. five times and Europe another three with Dave, recording two albums - 1988's No More Censorship and 1989's Fumble (released in 1993). But bassist Skeeter Thompson's drug problems - he once tried to get paid for a show in cocaine - caused endless difficulties, eventually leaving the band homeless and penniless in Los Angeles in September 1990.

It was there that the drummer decided he'd had enough.

"I heard the Melvins were playing. I called Buzz [Osbourne, the Melvins' singer] and he said Nirvana were looking for a new drummer and that Kurt [Cobain] and Krist [Novoselic] had seen a Scream show in San Francisco and really liked my

drumming.

"I called Krist and he said they already had Dan Peters from Mudhoney. Then, about four hours later, he called back and said 'You know what, maybe you should come up here...'."

Nirvana were in a state of flux in 1990. Their debut Bleach had gained them some notoriety - especially in England -while

tours across America in 1988 and 1989 had done much to raise their profile. However, tension had been growing between Kurt

and their then-drummer Chad Channing. The problem, as Kurt saw it, was what he called Chad's preference for "elfin music".

What the singer wanted was someone to stamp his authority on the "heavy pop music" he wanted to play.

The frontman had met Dave twice before, but it was after seeing Scream that Kurt noted that he "beats the drums like he's

beating the shit out of their heads". He would later add, "he was the drummer of our dreams".

Dave's first Nirvana gig was at Olympia's North Shore Surf Club on October 11, 1990, and, though musically the new three- piece gelled, personally they hadn't. "We would sit in this tiny shoe-box apartment for eight hours at a time without saying a word," Dave later admitted.

It would take a UK tour to change things. Kurt suddenly had the firepower he wanted behind him, while Dave was now headlining the 2,000-capacity Astoria, instead of the toilet-circuit venues in which Scream performed.

"The first time we came to England, I thought it was great," he recalls. "We were playing in places that held 1,000

people, staying in nice hotels. When I was in Scream, we were living off $5 a day, sleeping in the van, on floors. So to be

playing big places, having my own bed and being able to smoke two packs of cigarettes a day was a big fucking deal to me."

Nirvana insiders claim that Dave had a more important role in the band than simply being the drummer. Though his powerful

playing helped make Kurt's riffs clear and potent, his outgoing nature became the glue between all three members.

So it was that Nirvana's relationship was forged on tour and, importantly, during the recording of Nevermind in May 1991. At

night after recording sessions were finished, the band would drive around the Hollywood Hills, as the drummer remembered,

"Krist driving, me in the back, Kurt in the front. We'd be drunk on big cups of 7Up and Seagram's 7 whiskey". It was the calm before the storm.

"Recently, the Foo Fighters played a show in Los Angeles," Dave said in 2007. "They had all these current alternative

bands on the bill. I'm looking at these kids thinking, That must be a mind-fuck to be selling millions of records at 22'.

Then I stopped and thought 'Fuck, man I That happened to me'."

Though Nirvana's record label, Geffen, only printed an initial 50,000 copies of Nevermind, secretly admitting that they thought they'd be lucky to sell 250,000 albums, it had knocked Michael Jackson from the Number One album chart spot just

months after release. It would go on to sell over 10 million copies, remaining in the British charts for a massive 184 weeks.

Within 18 months, Dave had gone from being homeless in Los Angeles to being in the biggest band in the world, with Kurt, the

man he'd spent glum days with in a silent Seattle apartment now, suddenly, 'the voice of a generation'.

"1991 through to 1994 was my crash course in how to be a rock star," he later said. "It was horrifying!"

With that pressure came trauma, especially for Kurt Cobain. His heroin use spun out of control, while his bond with Dave and Krist worsened as his relationship with Courtney Love grew. First the singer bullied the band into agreeing to a greatly reduced share of Nirvana's royalties. Next they would play massive stadium-sized shows across South America, something the anti-rock star in Dave hated. He later admitted he would be playing while wondering, "What the fuck are we doing? What is this about?".

In February 1993 when Nirvana recorded In Utero, their third and final studio album, they managed to put their escalating

internal problems behind them. But that good spirit would be short-lived. On July 23, Kurt overdosed on heroin in New York.

Under a year later, the singer overdosed again in Rome, this time on champagne and Rohypnol.

"Someone told me he had died and he hadn't" Dave confessed years later. "I completely lost my shit. And then someone called back and said, 'No, wait, he's not dead'. I was just numb. I was confused. I was already in mourning. And after that, it really was only a short time before he died."

On April 8,1994, Kurt Cobain's body was found in his home in Lake Washington. Following their friend's suicide, Dave and Krist withdrew from the glare, refusing to speak publicly for months.

"I miss Kurt," Dave went on to reveal. "I have dreams about Kurt all the time. He shows up and I'm, like, 'Holy shit! You're not dead', and it's like it was some big joke. Then I wake up... I have great dreams about him and I have sad, heart-wrenching, fucked-up dreams about him.

"I miss it all a lot. I miss Nirvana with all my heart. I listen to live bootlegs all the time because I miss it so much. But if you're dealt a fucking hand, then you deal with it. If there's anything I've learned, it's that you've got one life and you'd better live it as best you can. I'm not going to sit back and be some pitiful fucking mess."

What Dave did, after Kurt's death, was immerse himself in music.

"After Kurt died, I basically just did no music and travelled for a while," he remembers today. "Then the first project I did after Kurt died was playing the MTV Movie Awards in 1994 as part of the Backbeat Band we did one song [The Beatles'

Money], I met [former Minutemen, now Stooges bassist] Mike Watt and he said, I'm making this record, wanna play drums on

it?'. So we went to Robert Lang's studio in Seattle and did a couple of songs there for his solo album ['95's Ball-Hogg Or

Tugboat?]. So then I thought, 'Okay, I'm gonna get my shit together and demo some stuff at home and then book a session for

myself.

"So I booked six day? with [producer] Barrett Jones and was totally prepared to go and record these 13 or 14 songs," he adds. "It was some cathartic thing, I needed to punch through this plate I'd been trapped in for a while and I thought this would

be the best therapy for me,

"I think I might have made 100 cassettes and I'd give them to people when they'd come over. Around the same time [Pearl Jam frontman] Eddie Vedder did a pirate radio-type show and he played a demo of the song Exhausted. I remember him saying, 'I love this song, it makes me want to drive off a cliff'or something. So Eddie gave me my first big break! And then suddenly record companies were calling my house..."

The result of Dave's sessions was the Foo Fighters' debut album (which would go on to be released in July '95) and it took less than a week to make.

"It wasn't supposed to be a major release," he admitted later. "It was just recorded down the street from my house in five days. Had I intended it to be a full release, I would have spent more than five days on it!"

"No matter what I do, whether that's the Foo Fighters or something else, I'll always be the guy who played drums for

Nirvana. I'll never escape my past. I'm not sure I want to," said Dave, years after that band's demise. However, with the Foo Fighters' debut, escaping his past was exactly what he had in mind.

Initially, he planned to release the album without his name on it. When that proved impossible, he implored his record

company not to arrange glitzy launch parties, nor for his agent to book him into big name venues. He also refused to do any

interviews, knowing full well what the questions would concern.

Next he had to find a band. When the local and influential Sunny Day Real Estate broke up, he immediately poached their bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith. For a guitar player, he asked Pat Smear, The Germs' former guitarist, who had been a part of Nirvana's touring set-up, to join.

"When we started this group, I just wanted to make it seem real and in no way contrived. You know, this pretentious, rising- from-the-ashes-of-despair thing. It was, like, fuck that!"

And so it was that Dave began to enjoy himself. Returning to his punk roots, he set off across America with his new bandmates in a modest van, which he piloted himself. "I think a concert should be intimate," he said of the small-scale tour, in which he revisited many of the venues he had played in Scream and Nirvana's early days. "I've always thought, 'how could you have fun at a concert if the singer of the band didn't dive out and land on your head?'."

Despite his fears that "I don't know if anyone is ever going to be able to consider us a valid rock unit," Foo Fighters had begun the journey from Nirvana's shadow.

Foo Fighters' line-up was not a solid one. In February 1997, William left, upset that Dave had re-recorded some of his drum parts for their second album The Colour And The Shape. Next to go was Pat Smear (although since 2006 he's been playing as a touring guitarist). Alanis Morissette's drummer, Taylor Hawkins, came onboard, while Franz Stahl, the frontman's ex-Scream friend, joined on guitar.

For two years the band toured, before reconvening for the 1999 sessions for their third album. There Is Nothing Left To Lose, when Franz became the next to jump ship. "I was in tears." Dave said of his departure. "He was one of my oldest friends and we wanted it to work so badly, but it didn't."

It sent the band into a spin, with Dave entering a period of introspection. He reacted by fleeing Los Angeles to his home state of Virginia, muttering, "I fucking despise this city. Everything about it is just vile," as he went.

The results of their self-imposed Californian exile were perhaps the band's most unified body of work - hook-laden, confident and taking on all comers, their third album earned them a Grammy for Best Rock Album. It was followed, meanwhile, by the addition of the former No Use For A Name guitarist Chris Shiflett to the ranks.

Still, though, harmony was thin on the ground in the years that followed. Taylor fell into a two-day coma amid rumours of heroin use - later, he admitted, the blame lay with painkillers - while 2002's One By One was both the band's least rewarding and most troubled album to date. The problem was that the frontman had grown so disillusioned with the band that, midway through the recording process, he jumped ship to join Queens Of The Stone Age on drums. Chris Shiflett, for one, thought Foo Fighters were over, admitting he believed, "Dave was going to break up the band. I think everyone did".

"I thought, 'Well, that was fun and we've had a good run at the thing'," Dave confessed at the time. "So, yeah, for a minute I thought we should call it quits."

Far from the happy-go-lucky image that Dave projects, it seemed there was a dark side that he kept well hidden. He admitted

to Q Magazine that he'd been in and out of therapy for years, saying, "Every once in a while I feel like, 'What the fuck am I doing?'."

"It's nice to be called 'the nicest man in rock'," he admits "But it's funny to me because the guys in my band would probably tell you otherwise... There's a side of me that's so fucking territorial, certain things make my claws come out and

turn me into a fucking very difficult person.

"I do have borders and boundaries. There're certain things where I'm like, 'Man, don't even fucking go there'. The most

important thing for me is my family, my health and happiness and making sure everyone's cool."

But the 2005 double album In Your Honour, featuring an acoustic and electric side, served as decompression - as did his star-studded metal side project/tribute album Probot (one of his many extra-curricular activities), released the previous year.

"There shouldn't be anything wrong with being in 17 bands if you want to be," he explains of his love of getting involved in

other projects. "I understand loyalty and exclusivity, but as a musician, there's nothing better than experiencing as much

music with as many people as you can, because you learn so much."

And after the release of the Foos' fifth album, rather than reject his rock stardom, it seemed that Dave had finally learned

to embrace it and enjoy it.

"Every record we've made I always imagined would be the last," he said after In Your Honour's release. "But, for once in my life, I've made a record I don't want to be the last."

With his newfound comfort, came a reversal of his attitudes of old. He was in his element playing to tens of thousands in Hyde Park in June 2006. The 2007 album Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace was a more contemplative, mature affair, but lead to two nights at Wembley Stadium last year, complete with a guest appearance from Led Zeppelin. This from the man who, 15 years earlier, had felt uncomfortable playing stadiums in South America with Nirvana. What changed?

"It was frightening," he recalls. "There was only one way to get over it and that was just to say, 'Fuck it!'. From then on, I didn't worry about it and I haven't since."

The recent release of the band's Greatest Hits (which, at the time of going to press, was on course to enter the UK Album

Chart at Number Four) seems to mark the end of another chapter, with Dave, who turns 41 on January 14, admitting Foo Fighters will take a break before releasing new music. But his newest project Them Crooked Vultures will keep him busy and not far

from a venue near you for the time being.

From playing in hardcore bands in squats across Europe, to sold-out Wembley Stadium shows, establishing himself as a premier frontman on his own terms, selling in excess of eight million records worldwide with the Foos alone, winning five Kerrang! Awards (including the coveted Hall Of Fame accolade), six Grammy Awards, and two BRIT Awards- all while becoming one of the most respected and popular musicians in the world - Dave has come a long way. A lot further than he thought possible.

"I was grilling up food on a barbecue before we went onstage at Hyde Park," he remembered in 2006. "I remember thinking, 'Okay, there are 85,000 people here and Motorhead is playing as our support band'.

We had 1,100 employees that day and it was all because of this demo tape I did for fun 13 years ago.

"I had a moment there where I thought 'How the fuck did this happen?' You have to remember that this band started on the basis of making music that no-one was supposed to hear. That's always been at the root."

Words: Tom Bryant