"It's funny — for years, I've been navigating in and around the shadow of Nirvana," he says. "When I say shadow, it's not meant to sound negative, it's a reality. It's the truth, you know. When [Foo Fighters] first started as a band, I didn't want to talk about Nirvana because Kurt had just died and it was hard for me to talk about it without getting really upset. Then, as time went by, it was easier to talk about. But there was more to talk about with the Foo Fighters. And the Nirvana questions sort of went away. Of course, now they are coming back."

There's a reason: the fast-approaching 20th anniversary of Nirvana's Nevermind, the album that immutably altered the face of popular culture and set the tone for the entire

aesthetic of the 90s. In a coincidence which, when he thinks about it, isn't a coincidence at all, Foo Fighters' new record, Wasting Light, finds Grohl reuniting, old-school style, with Nevermind producer Butch Vig and the Nirvana guitarist Krist Novoselic. When they sat down to work on a song in Dave's converted garage in Los Angeles a few months back, it was the first occasion all three had been in the same room together for two decades. Even thinking about it brings on a flush of emotion.

There's a reason: the fast-approaching 20th anniversary of Nirvana's Nevermind, the album that immutably altered the face of popular culture and set the tone for the entire

aesthetic of the 90s. In a coincidence which, when he thinks about it, isn't a coincidence at all, Foo Fighters' new record, Wasting Light, finds Grohl reuniting, old-school style, with Nevermind producer Butch Vig and the Nirvana guitarist Krist Novoselic. When they sat down to work on a song in Dave's converted garage in Los Angeles a few months back, it was the first occasion all three had been in the same room together for two decades. Even thinking about it brings on a flush of emotion."When I asked Krist to come down and hang out with me and Butch it was almost not musical," says Grohl. "It was personal. There is a much deeper meaning to it."

Sitting forward, so that you glimpse the matching eagle feather tattoo on the outside of each arm, he continues: "For years, I would not write songs because people would think it was about someone or something that had to do with Nirvana. It was after the birth of my first child I thought, you know, I'm a father now. I don't have time to be afraid of anything. There are more important things in life than worrying about what a fucking journalist is going to think about this song. So I'm going to write it. I'm going to work with Butch, if I think it's time. It's liberating to be able to do it."

Since Cobain's death, Grohl has arguably dedicating himself to helming the anti-Nirvana. With a bouncy mosh-pit sound and an uncomplicated attitude towards fame and success, Foo Fighters have proceeded with the business of being a global rock brand without any of the authenticity issues that chewed up Grohl's previous outfit. When he sees groups such as Arcade Fire so publicly agonise over their journey from the underground to the enormodome, does he see the worst kind of history repeating itself?

"The most important thing when Nirvana signed a major label deal is that we were still Nirvana," he says. "The difference between Nirvana selling 50,000 records and Nirvana selling 50 million records is only the number of albums. Our intention never changed. The music didn't suffer from that. The music responded to it — but it didn't suffer from it. I really think people should stop worrying about guilt and cool...

"Arcade Fire are one of the best bands in the world, they have so much to offer. I can understand they are risking some of the really strong emotional ties they have with the scene they are outgrowing. Musically, I have faith they will never suffer due to the amount of people that listen to them. Radiohead is a great example. They went from being a smaller club band to one of the biggest bands in the world without their integrity suffering. Foo Fighters are the same. Yeah, we're selling out stadiums. Put us in a room and we're the same fucking band we were in 1995. Guilt kills people. It's not fucking cool. Don't get me started on guilt."

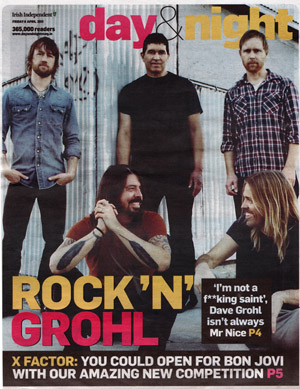

At 42, Grohl has eased into the role of rock elder-statesmen. He is every bit as amiable and unaffected as reputation suggests, though with that inbuilt "wariness of journalists standard among the very famous. In a black T-shirt and jeans, hair flopping around his ears, he hasn't aged very visibly since Nirvana. Without projecting any sort of hackneyed rock star 'aura', he is self-contained and radiates a poise at odds with the tumult he unleashes when he straps on a guitar or climbs behind a drum kit.

Not that he's a soft touch. A few weeks after our interview, for instance, he will be embroiled in a public spat with Glee creator Ryan Murphy after turning down the opportunity to have his music featured in TVs pre-eminent kitsch fest ("fuck that guy for thinking anybody and everybody should want to do Glee").

A relentless salvo of upbeat pop-rock, what saves Wasting Light from qualifying as mere headbanger fodder are Grohl's strident melodies and his ear for a stomping great hook. Accompanying it is a two-hour rockumentary chronicling the band's emergence from the ashes of Nirvana — their 1995 debut consisted of the self-recorded demos Grohl put down while grieving for Cobain — and their progress to the point where, in 2008, they packed London's 70,000-capacity Wembley stadium two nights running.

Although the story is familiar to anyone with the vaguest interest in the group, it still makes for absorbing watching, particularly when Grohl's ruthless streak comes to the fore. In one fascinating segment, he recalls covertly assembling the Foos in Los Angeles so that he could re-record their second album without their drummer, who, in faraway Seattle, gradually started to realise he was being incrementally shafted. It doesn't quite chime with Grohl's billing as 'nicest guy in rock'.

"I always felt it was kind of the funny that I got the nicest guy in rock thing. When I saw the first cut of the film, I watched a few of those uncomfortable moments and thought, yeah I've had to do things people wouldn't consider kind. I'm not a fucking saint you know. If I wanted to be a priest, I'd be a fucking priest... I always laughed at the 'nicest man in rock' thing. Yeah, I could sit around in the pub and make you laugh for an hour. It isn't that one-dimensional. I'm a fucking human being, you know."

He is reminded of a conversation he had just before joining Nirvana. "When my hardcore band Scream broke up and I was stranded in Los Angeles, I got a call from my friend Buzz, who was in the band Melvins, saying, 'hey, Nirvana are looking for a drummer, they really like the way you play". I had nothing going on in Scream and I had this opportunity to keep playing music. I call my mother for advice. She said, 'I know those people in Scream are your best friends and are like your brothers. There are some times in life where you have to do what's best for you'. And I did, and I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for that."

Along with the Nevermind anniversary, 2011 marks 20 years since Nirvana's semi-legendary dates with Sonic Youth at McGonigles in Dublin and Sir Henry's in Cork. With grunge about to blow up, did Grohl feel he was on the brink of something huge at the time?

"Cork was the first one. My mother has Irish ancestry. That was my first time in Ireland. I remember waking up in the morning, walking around Cork. I ran back to my hotel room and called my mother — 'Mom, all the women look like you!' And yeah, it was the first time I had seen an audience so enthusiastic. They were going fucking bananas. And that was just before Nevermind came out. So it was sort of like... well, I hate to say it was the calm before the storm because it was pretty fucking insane. But if you can imagine that being the calm, try imagining the storm."