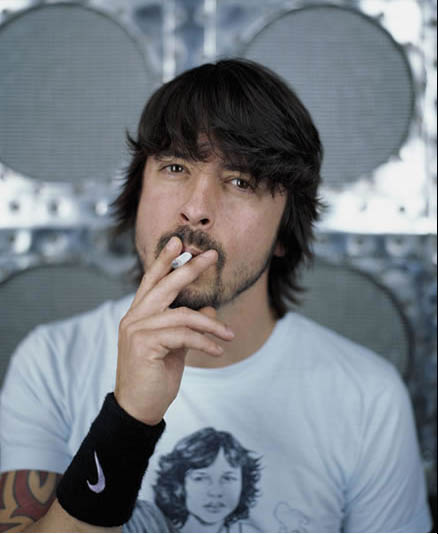

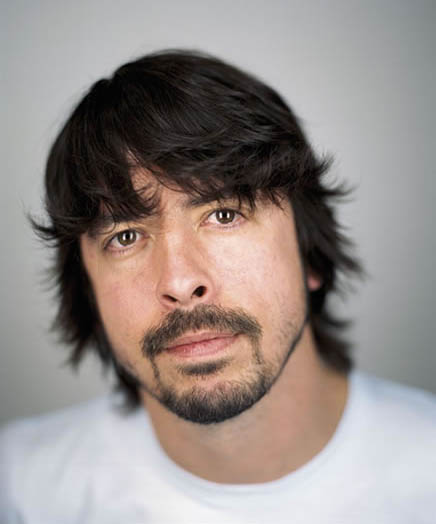

Harp

Foo Fighters new album, Nirvana & the day that changed his life forever.

It was July 1994, some three and a half months after Kurt Cobain’s suicide, and after months of anticipation, the fourth annual Lollapalooza tour had finally reached the Detroit suburbs. Fifteen-thousand of us had come together at the Pine Knob Music Theater in Clarkston, Mich., for a day of alt-rock bliss that included performances by Smashing Pumpkins, Beastie Boys, the Flaming Lips, A Tribe Called Quest and the Verve. Just before dusk, after hours of baking in the oppressive summer sun, I randomly found myself in a secluded area of Pine Knob, descending a cliff-like wooden staircase during a break in the mainstage action. And right there, walking alone some 10 or 12 steps below me—to my complete shock—was Dave Grohl.

Since Kurt Cobain’s suicide in early April, both Grohl and bassman Krist Novoselic had been MIA. No one in the media, it seemed, was able to reach either of Grohl’s former bandmates, leaving all to assume that they were holed up indoors, mourning. Even if they weren’t, running into Grohl among the masses at Pine Knob seemed unlikely, impossible.

But there he was, and there I was. Spying my shock from beneath his black Sepultura baseball cap, Grohl stopped to say hello. Visibly still shell-shocked from Cobain's death—you could see a bit of hurt lingering in his eyes—Grohl was uncharacteristically shy, flashing none of that toothy, knuckleheaded wit with which he would charm us over the next decade. Searching for something cool to say, I raved about the Backbeat soundtrack, a new early-Beatles tribute that Grohl had played on.

Before he had a chance to respond, I popped the question: “How are you?" (In my 20-year-old head, it didn't seem impolite.) “Good," he knee-jerked. As awkwardness set in, we chatted for another minute or so, shook hands and that was that. It was ironic, I remember thinking at the time: Prior to Cobain's death, Nirvana was slated to headline the tour.

But it wasn't what he said that day that I remember most, but the image of him walking away, down the wide, concrete pavilion steps. As he passed throngs of fans readying for the Breeders' set, he slipped by anonymously, with his hat pulled down low. As he made his way into the audience to rejoin his then-new bride, from nearby Grosse Pointe, Nirvana’s “All Apologies" spilled out of the PA and the crowd—God bless it—replied with a roar. It was at once immensely beautiful and deeply sad. As the song’s chorus arrived, with Cobain groaning “In the sun/In the suuun I feel as one,” Grohl found his row and began inching his way toward his seat, keeping his head down the whole time.

Fast-forward 11 years, and I’m almost finished interviewing Grohl for this piece when I somewhat tentatively remind him of our first encounter. After nearly an hour of machine-gun responses, it’s the first time he pauses.

“I remember that. I totally remember that,” he says, almost excitedly, but with a hint of sadness in his voice. “When the audience started cheering, I got really choked up, because I thought, ‘Whoa, we were supposed to be here, doing this. What happened?’ That was a really strange time for me. That whole year was”—he stops and restarts—“It’s still kind of a blur, because I think I was kind of wandering. But that was the first time I realized what sort of impact music, or Nirvana’s music, had on people: that they were actually going to miss it. And so was I. I got really choked up,” he says, sighing.

“It’s funny that you remember that because I think about that every once in a while. Sometimes when I hear that song, I think of that day. That’s when I started thinking, ‘Oh my god, something I’ve done really became a part of millions of people’s lives.’”

Looking back, I’m sure there wasn’t a kid in that pavilion or on that lawn that day, nor a single A&R man in Hollywood or bookie in Vegas who could have foreseen Grohl’s decade to come: As the face of and the force behind the Foo Fighters, the band he debuted the year after Cobain’s death, Grohl has gone on to pull off the utterly impossible: In transforming himself into punk rock’s answer to Phil Collins—the only other notable drummer turned bandleader/singer/songwriter/celebrity—he’s remained a part of the lives of many of those millions while attaining near living-legend status among generations Y and Z. Who knew the title of the Foos’ inaugural single, “I’ll Stick Around,” would prove so prophetic?

Certainly Grohl didn’t. By his own admission, he’s just as astonished as the rest of us that the masses remain so faithful a decade later. Grohl’s friends and peers describe him as endlessly motivated, and always eager to get started on a new Foo album, a new side project, a new tour, or ready to hop into the studio with a friend, hero or admirer (he’s become the “it” drummer in recent years, backing the likes of Queens of the Stone Age, Tenacious D and, most recently, Nine Inch Nails). And that drive, he says, has always been rooted in the feeling that it could all end tomorrow.

“The Foo Fighters weren’t supposed to be here 10 years later making double albums,” he says, referring to the most ambitious project of his career thus far, the new Foo Fighters release In Your Honor, an album that’s sonically split in halves. The first disc is composed of the vein-popping melodic punk that has become the band’s calling card, the second an all-acoustic album that even features a bossa nova duet with Norah Jones.

While the Norah Jones cut, “Virginia Moon,” was a bit of a shocker—a pleasant one at that—the acoustic album isn’t completely out of left field: The Foos have experimented with midtempo fare and acoustic guitars on songs like “Walking After You” (a Norah fave), and in recent years Grohl has strummed covers on late-night talk shows. He even hit the campaign trail with John Kerry doing the acoustic troubadour thing (his playing before teachers and veterans partially inspired the new album’s title). “We always knew that we had it in us,” he says. “It was just a matter of doing it when it feels right. But I’ve always had a love of that gentle, delicate dynamic, whether it’s Neil Young or Ry Cooder or fuckin’ Cat Power. There’s a part of me that feels that’s more powerful than the best Black Sabbath record sometimes.”

In Your Honor was born out of a time when Grohl, who after divorcing his first wife, remarried in 2003 and turned 36 in January, started taking stock of his life, surveying the past. “After we finished touring for the last record I got home from that year-and-a-half on the road and started thinking about the 10-year anniversary of the band, all we’ve accomplished in the last 10 years, all the shit I did before that and how long I’ve been on the road—since I was 18 years old.

“I’ve always felt like there’s a point in this touring/music/Foo Fighters thing where it’s just gonna stop, or kind of let go of me and let me do my own thing in life—just, like, to have children, or go back to school, whatever. It’s a charmed lifestyle, and I feel like the luckiest guy in the world, but there are times when I feel like A) it’s too good to be true and B) I can’t do this for the rest of my life: There’s got to be something else. I mean, I can’t imagine it’s the only thing I’m able to do. So I just started thinking about everything, whether the band should continue for another 10 years, or whether we should call it a day.”

With all that brewing in his head, that new direction found him about two years ago, when he started writing a batch of sleepy acoustic music akin to the songs filling Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas score. “I started talking to my manager, and I said, ‘I think I want to do a record by myself. I don’t want it to be a solo album, but I’d love to make an acoustic album. So maybe I could pull a Tom Petty and find a movie that needs a score, like he did with She’s the One.’

“So I started writing for that, and then I realized there’s nothing I love more in my life than the Foo Fighters, my friends in the band and my family in the crew, and what we do when we jump up on a festival stage in front of 60,000 people. I’m blessed with this thing, so I can’t just sort of push it to the side and throw it away. So why not make this acoustic album the next Foo Fighters album? I started thinking rather than travel the same road that we’ve been on for 10 years, it’s time to stop and make a left and go off into some territory that we’ve never experienced before. I thought the acoustic stuff would be a nice change of pace. After getting into that for a few weeks, I thought, ya know, I need rock. I need metal. I need audiences beating the hell out of each other for an hour and a half. It’s just what I love the most.”

While In Your Honor’s first half is by-the-numbers Foo crunch—which, like its predecessors, immediately scored a rock-radio hit in the anthemic scorcher “Best of You”—disc two finds Dave and the gang experimenting with keyboards and organ for the first time.

“It was almost a learning experience for him, seeing what in the keyboard world will work for him,” says Wallflowers keyboardist Rami Jaffee, who guests on half of the acoustic disc. “He’s pretty focused on what he wants in his songs, and this was a weird area for him. When I first got to the studio, he wasn’t sure how it was going to sound with his songs. He said, ‘Why don’t you just try some stuff,’ and we quickly realized what wasn’t going to work for him: He doesn’t like pretentious ideas and sounds. I had a few wacky keyboards, some pump organs and accordion organs and when I got to the more eclectic stuff, he was kind of weary, he didn’t want too much of that.”

Not having a single power chord or swell of distortion to hide behind, Grohl says the acoustic disc raised the stakes for him lyrically. “With the rock record, a lot of those lyrics were written to be shared with millions of people. They’re emotions and feelings that come from a real place, but they’re meant to be anthemic, whereas the acoustic record is far more personal. On an acoustic album, if there’s just a guitar and vocal and some somber melody, you can’t sing about bubblegum and puppy dogs, you have to dig a little deeper than that.”

Distortion or no distortion, the lyric-writing process remained the same: it came last. Make that last minute, at least for the Norah track “Virginia Moon,” Jones says. “When I got to the studio, Dave was like, ‘I just wrote the lyrics this morning,’ and it was good. I was like, ‘Wow. I can’t really work like that myself, but I’m surprised you did this so quickly.”

Originally Jones, a longtime Nirvana and Foo Fighters fan, was hoping her call from Grohl would yield a chance to show her metal chops. “I was like, ‘Coooool, I get to rock,” she says, laughing. “And then he tells me that they were doing a rock CD and a mellow CD, and I was like, ‘Ohhhh, lemme guess which one you want me on. But it was cool, I didn’t care, whatever he wants I will do. The first—and probably the only—time I played air drums was in junior high listening to Nirvana.”

More than Nirvana, more than the Foo Fighters’ 10-year anniversary, the acoustic half of In Your Honor underscores just how far Grohl has come. Twenty years ago, his life’s ambition was to simply “be in a band that was a fucking blitzkrieg, do van tours and fanzine interviews and have the coolest fliers.” Today, it’s a little more far-reaching.

Born January 14, 1969, in Warren, Ohio, the son of an English teacher and a journalist, Grohl was three when his family moved to Springfield, Virginia, where his fascination with music began with the Beatles and a guitar. But Rush’s 2112, he says with a laugh, altered his course. “It was the first time I’d heard music where the drums were almost the most prominent instrument. It’s funny, although I was a guitar player, my locker in eighth grade was covered with cut-outs from magazines of different drum sets, just because I thought drums looked like some sort of sexy machine or something.”

In his early teens, he switched to drums, started smoking reefer—igniting a lifelong obsession with Led Zeppelin (he couldn’t be more stoked about John Paul Jones’ cameo on In Your Honor)—and following D.C.’s burgeoning hardcore scene, where he began cutting his teeth in the shadow of such local heroes as Bad Brains, Minor Threat and Black Flag. Bashing away in Mission Impossible and Dain Bramage, Grohl was a natural.

“I remember the first time I saw him,” says Dante Ferrando, owner of D.C.’s the Black Cat and a drummer in several local hardcore bands in the early ’80s. “I asked him how long he had been playing, and he said six months. He was at the same level as me, and I had been playing for five years. He wasn’t doing anything really fancy, but he had power, and he was really on. He had a crisp, hard-hitting, dead-on sound. He was nailing it.”

When he tried out for the open stool in one of his favorite groups, Scream—a local heavyweight that, unlike many of its peers, had done some substantial touring—he told the band he was 19. He was 16. No matter, he got the job—but not before Scream caught a Dain Bramage show at D.C. Space. Remembers ex-Scream singer Pete Stahl, “Everyone in the audience seemed to be watching him playing drums. Everybody was just watching him instead of the other guys in the band.”

Dropping out of high school and jumping into the Scream van in 1987, Grohl was in punk-rock heaven. But after three years, one studio album, two live discs and countless shows, the band started to unravel. In September 1990, midway through a U.S. tour, Scream fell apart after its bassist abandoned the group in L.A. While crashing at Stahl’s sister’s place in L.A., relying on help from his mom, Grohl phoned Buzz Osborne, the singer in Seattle sludge-punk band the Melvins, who mentioned that the fledging Sub Pop trio Nirvana was looking for a drummer. He passed along Grohl’s number to Novoselic, and within days he was touching down at Sea-Tac Airport.

If he and Cobain were polar opposites personally, musically they were a perfect union. “We knew in two minutes that he was the right drummer,” Novoselic tells Michael Azzerad in Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana. “He was a hard hitter. He was really dynamic. He was so bright, so hot, so vital. He rocked.”

All teeth and hair, a shirtless Grohl made his official debut with Nirvana on October 11, 1990, at a sweaty, cymbal-cracking show at the North Shore Surf Club in Olympia, Wash. (priceless amateur footage of which is included in last year’s Nirvana box set, With the Lights Out).

If Nirvana fans were left slackjawed by Grohl’s immediate post-Cobain success, it’s because most of the world never knew he was much of a singer, guitarist or songwriter. So it begs the question: Why didn’t we? Why didn’t he have a bigger songwriting presence in Nirvana? The answer: Because he never wanted to be anything more than the drummer.

“The greatest thing about being in Nirvana is that I got to play the drums. And as much as I love writing music and being the singer of the Foo Fighters, I loved being the drummer of Nirvana, because my job was so basic and simple. I was supposed to be the fuckin’ bulldozer that carried Krist and Kurt through every show, and it was simple. Kurt’s music was so beautifully simple. And when you get the right combination of people playing together, no one is trying to grab the mic or pull the spotlight, everyone is doing their part, and you just serve the song.”

By the time Grohl joined Nirvana, he had been writing songs for years, and had recorded several tracks in friend Barrett Jones’ basement. It was actually Cobain who gave him the confidence to make songwriting more than just a hobby.

In 1990, not long after he joined Nirvana and moved into Cobain’s Olympia apartment, Grohl was up late one night recording a song called “Marigold” on the 4-track in the living room. “I just did a guitar track and some layered vocals, and Kurt was in his bedroom on the other side of the wall. I thought he was sleeping, and I was trying to be as quiet as possible. He came in while I was listening back really, really quietly and said, ‘What is that?! And I said, ‘Oh, just something I just recorded.’ He’s like, ‘Whoa, show me the guitar thing, show that to me.’ And we used to kind of jam on it in the living room. That was probably the first time I ever thought, ‘Wow, maybe I can write songs.’”

While his writing credits may have been minimal during the Nirvana years, Grohl was becoming more accomplished as a guitarist, bassist and songwriter. So much so that, just a year after Cobain’s death, he compiled a collection of his songs—some old, some new—and released them through Capitol Records as Foo Fighters. The disc featured a photo of the band’s first lineup, but Grohl played every instrument and sang every vocal, with the exception of a brief guitar cameo from the Afghan Whigs’ Greg Dulli. “I just wanted something that people would imagine to be a gang, or a team, or something,” he says of the band’s name.

On the band’s first club tour, during which they pulled double duty as both opener and band for Mike Watt, the myth of Cobain loomed large. Sixty to 70 percent of the audiences were wearing Nirvana t-shirts. While Grohl took it as a show of loyalty, the hero-worshipping would get a bit weird as time wore on. “I’ll never forget going over to Ireland—just to escape—and driving through the middle of nowhere, down a stretch of road where there’s nothing for 40 miles, and seeing a hitchhiker with Kurt’s face on his shirt. I was just like, ‘oh my god’”—laughing in disbelief—“‘what has this world come to?’”

By his own admission, Grohl’s suspicion of the attention given to the Foos early on helped generate the it-could-all-end-tomorrow vibe. Were people playing his records and videos, and were fans buying his records and packing his gigs just because he used to be in Nirvana? For years, a need to distance himself from his past kept him from his first true love: playing drums.

But all that changed in 2002, when raunchy desert boozers Queens of the Stone Age, friends through Scream’s Stahl, extended an invitation to covertly bash away on their second album. Officially burying the past, Grohl helped catapult the Queens’ Songs for the Deaf into the rock stratosphere, and ended up unlocking the door to his drumming dreams: In the past three years, Grohl has backed everyone from Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommi and Killing Joke to Lemmy from Motorhead and Sepultura’s Max Cavalera to Garbage and Nine Inch Nails.

“The Queens thing was a turning point,” he explains, “because there were no other bands that I would have done that with. They were my favorite band, and they were a band that connected with my drumming, and there aren’t many of those at all. Killing Joke? Yeah. Fuck yeah. When Killing Joke called up and asked me to play on their record, I knew it would work because my drumming comes from the same place that Killing Joke does. But the reason they called is because of the Queens record. It was the first time I had done a full LP with anyone since Nirvana, and it was fucking good.

“If Queens came knockin’ on the door and said, ‘Ya know what, we’re gonna need you back for a month and a half,’ I don’t know what I would do. That’s tough. I mean, I’m married to the Foo Fighters, but the Queens guys are like—they’re like the hottest fuck I ever had in college. And when that one comes knockin’, the question mark pops up big.”

Grohl’s return to drumming couldn’t have happened in a better way. Because it was kept quiet that he was playing on Songs for the Deaf, plus the fact that his role in the group was only temporary, the pressure was taken off of everyone involved, says Queens frontman Josh Homme. “We both were inspired and freed up playing music together, and the communication was telepathic. It was like being the only person who speaks Latin for too long: When you finally meet someone else who speaks it, you try to use every word in your vocabulary.”

As if he didn’t reign already, Grohl was crowned king badass of the rock realm when Nine Inch Nails mastermind Trent Reznor requested his services. Interestingly, Reznor was drawn to Grohl not because of the Queens record, but for his work on Killing Joke’s 2003 self-titled release.

“I think his work on the Queens record is superb, but it was more the Nirvana stuff and then the Killing Joke record that blew me away,” Reznor says. “Dave just makes live drumming sound exciting! Plain and simple. He’s powerful and exciting and tasteful. I noticed a common thread on several records he’s played on that always called my attention to the drumming—something I usually don’t pay that much attention to as a listener. It was hooky, sometimes showy, but always appropriate and exciting. It always seemed to elevate the tracks up a notch or two. So, when I was writing With Teeth, I envisioned the tracks having a Dave Grohl-esque feeling to them.”

Essential to that Dave Grohl style, says Scream’s Stahl, is something that you can’t necessarily hear, but that you can certainly feel. “It’s a combination of talent and personality. Dave just naturally propels you forward. He gives you a little spark that people like Trent Reznor are always looking for, somebody to push them. When you hear something in your head, and you play it with other people, and it’s good and it’s almost there, Dave is the kind of guy who can push it where you want it—that’s why he’s in demand.”

“When he came in to play on my solo album, he was definitely full of energy,” says Sabbath’s Iommi. “That’s the first thing I noticed about him. He was so up, and it was great for us, because it made everybody else get that vibe off him.”

October 31, 2002. The Supper Club, Midtown Manhattan. It’s Halloween night and a few hundred industry-types and a handful of lucky college kids in town for the annual CMJ festival are all smiles. The Foo Fighters are about to treat the crowd to a rare club gig marking last week’s release of their fourth album, One by One. But first: a trick.

With the audience good and tipsy, the lights dim and the Foos hit the stage, readying themselves in the dark. Grohl starts grinding out a familiar riff, and bewildered faces turn to smiles as drummer Taylor Hawkins clobbers the symbols, thus cuing the lights: Decked out in matching black suits and white ties, the Foos are plowing their way through a paint-peeling version of the Hives’ omnipresent “Hate to Say I Told You So.” There isn’t a cynic in the house—Halloween has never been this fun.

It’s a classic Grohl stunt: Fun and funny, witty and cool. And the joke isn’t lost on the Hives themselves. A few weeks later at a Foo show in Europe a basket of flowers arrives backstage with a note reading: “It feels pretty good to be the Hives, doesn’t it!—Howlin’ Pelle Almqvist.” If anything has been the X-factor in Grohl’s career it’s been his unfailing sense of humor. When I asked several of his friends and peers for their funniest anecdote about Grohl, they all smiled and laughed: “There’s so many,” they all said. “He is definitely the life of the party, a great soul and funny as fuckin’ hell,” says the Wallflowers’ Jaffee.

“As a man, as a person, I don’t think Dave has changed very much in the past 10 years,” says Foo bassist Nate Mendel. “He’s still the happy-go-lucky, carefree guy who manages to put having a good time and art above the business and the mundane details of life, and I really admire and respect him for that. In addition, he’s the leader of this band, which means he’s got a lot of responsibilities. And I’ve really seen him grow as a person who knows how to do that while maintaining all those other qualities.”

So why is he still here a decade later? To Norah Jones, it’s simple: “He just writes great songs.” Opines Ferrando, “He really went for it, and worked really hard. He writes really good power-energy pop things that a lot of people can’t write—it’s rare that you can get somebody who can crank them out year after year. And he’s a really nice guy. And that can’t be overlooked. It makes a difference.”

From a musical standpoint, completely ignoring his audience has proven key: “I don’t necessarily take them into consideration when making music,” he says. “Of course, I’d love to have them included in a fuckin’ 6,000-strong sing-along. But the best way to do that is to disregard the audience and do what you do best on your own.”

The fact that he doesn’t sleep much doesn’t hurt. The night before I spoke to him for this story, he and his wife Jordyn went out for a big beachside dinner to toast In Your Honor’s first week—it bowed at No. 3 on the albums chart—and afterward Jordyn was in bed by 11, but Grohl stayed up until 3:30 a.m. strumming a guitar, enjoying his alone time, and just thinking and dreaming about music. “I wake up 50 times during the night, and when I look at the clock and see that the sun is up, I jump out of bed and just start going for it.”

He’s already got a name for his next side project: Non da Non, Italian for “nothing from nothing.” It’s the title of a photograph, a gift from an ex’s father, an Italian artist. “This double album just came out and I’m already looking forward to doing this project in 2006, and just blowing people away with a fuckin’ orchestrated mess. There’s a bunch of people I want to have on the record, but I haven’t talked to any of them yet. I literally just came up with this idea like two days ago.”

Listening to Grohl talk about the origins of In Your Honor, you start wondering if this may be the Foo Fighters’ last record, or if he’s hinting at a long hiatus. Yet in the very next breath, he starts waxing poetic about the band’s newfound potential. While he’s fairly certain that he’ll never release an album under the Dave Grohl name alone, changes are definitely on the horizon.

“I used to feel confined to what I consider the Foo Fighters sound, and now I don’t know what that is anymore. The acoustic album kind of breaks things open a little bit. And I’m just looking forward to going even further, and writing better songs, and building better orchestrations, and making things more simplistic, or making things more complex. It’s completely freed me musically. I feel like I’m no longer tied to this basic Foo Fighters idea. I feel like now I’m able to do whatever I want.”