Perhaps, but the thing is, I don't consider making music to be "work." A lot of the stuff that comes along with it definitely is, but walking into a studio and jamming with some friends? That doesn't seem like work at all-as much as I try to convince my wife that it is. I have these great opportunities that come up day to day, and I'm going to take advantage of them. I talk about imagining each new album to be my last, but I know I'm not going to quit playing guitar or drums any time soon. I look at a guy like Neil Young as a hero, and as such a good example of how to make a life out of making music. With that attitude it can last forever. I'm gonna be playing until I'm 112.

How did the idea for the acoustic half of In Your Honor come about?

After we finished touring for the last record I thought, Okay, I'm in my mid- to late-thirties now. Do I really want to run around festival stages screaming my head off every night?

I don't know, maybe it's time to start playing some music [laughs]. So I thought that, rather than just jump back into the album cycle, I'd see if I could find a movie that needs a score. One of my favourite albums of all time is Ry Cooder's Paris, Texas. I love that album - I've listened to it for years and years. So I envisioned finding a project that I could turn into my own version of Paris, Texas. After about a month of writing I thought, wait a second, this could be a killer Foo Fighters record. I'd hate to have pulled a solo album out of my ass in the middle of the best time of our lives as a band, so instead it became a Foo Fighters project.

You've made big rock albums in the past - you have a pretty good idea of how to record them, and what they'll sound like when they're done. That wasn't the case with the acoustic material on In Your Honor. How does the finished product compare to your original concept?

I really didn't know what was going to happen with that album, and I think that's why I consider it to be the best thing we've ever done. We were in a panic when we recorded the acoustic record. We'd spent about two months on the rock disc, and then one day I thought, Okay, I know when our deadline is, and if we don't start in on the acoustic album we might be fucked. Having never done anything like that before, I didn't know how long it was going to take. So we had a little meeting where I sat everyone down and said, "Here's what we have to do: Everyone has to be here all day, we need to do one song a day and no one's leaving until that song is done." And that's what we did. I'd get in front of a mic, someone would put a click track in my headphones, we'd find a tempo and I'd just roll an arrangement off the top of my head. And as everyone else was putting their parts down, I'd sit in the corner writing lyrics. And we pulled it off. In two and a half weeks we recorded 15 songs, of which we used 10. It was perfect.

Rock bands - particularly hard rock bands - often fail when they go acoustic because they're unable to alter their usual approach. You saw that so often on MTV's Unplugged.

That's totally true. When Nirvana performed on Unplugged we were very aware of that. We'd seen a lot of other shows where bands basically just strapped on some ovations and played their songs exactly as if they were using their Kramers, you know? We tried to make it different, a little more delicate and mellow. And even making this new record with the Foo Fighters, there were times where the songs got dangerously close to turning into rockers. For example, Taylor is an unbelievable rock drummer, and his first instinct is always to give you that 4/4 rock beat. But you have to rethink a lot of what you're used to doing. There were times where I'd have to say, "Okay, I don't think this one requires a whole drum kit. Could you just shake a tambourine or something?"

Unplugging a rock band can be risky business. Did you ever find yourself treading that line between sweetness and schmaltz?

Yeah, it was tough. Take a song like 'Virginia Moon,' which is a bossa nova. That's brand new territory for this band. At one point we put an organ on the song and it turned into something that you'd hear in an elevator. We had to tread lightly around some of these songs. That one in particular could have gone south real quick.

Lyrically, tracks like 'Still' and 'Friend of a Friend' have more of a singer/songwriter, storytelling approach than is customary in your material.

'Still' is probably the first song I ever wrote that comes close to any sort of storytelling. It's about my being a kid, going to the lake by my house on a Saturday morning and seeing all these ambulances and fire trucks because someone decided to kill himself by sitting on the train tracks. When you're a child, you're so naive, you have no idea what's really going on, and you start to explore and find yourself playing with pieces of the....it's a pretty gory story, actually, but it happened.

How about 'Friend of a Friend'?

That song was written out of loneliness. When I first joined Nirvana, I moved from the east coast up to Olympia, Washington, and into this little apartment with Kurt. And it was just so quiet - there was nothing to do. It was winter, and it was dark, cold, wet and dirty. Just depressing. The only thing there was to do was sit on the couch and play acoustic guitar for, like, 10 hours a day. So I wrote that song about these two strangers - Kurt and Krist - that I'd just met. It's basically about the three of us, at a time before Nevermind, before all of the fame and everything else. It's the first song I ever wrote on acoustic.

That song was written out of loneliness. When I first joined Nirvana, I moved from the east coast up to Olympia, Washington, and into this little apartment with Kurt. And it was just so quiet - there was nothing to do. It was winter, and it was dark, cold, wet and dirty. Just depressing. The only thing there was to do was sit on the couch and play acoustic guitar for, like, 10 hours a day. So I wrote that song about these two strangers - Kurt and Krist - that I'd just met. It's basically about the three of us, at a time before Nevermind, before all of the fame and everything else. It's the first song I ever wrote on acoustic.Are there any other acoustic songs from your past that found their way onto the album?

The main riff in 'Over and Out' is something I've been messing with for five or six years. And 'Virginia Moon' that's about eight years old. It's just my lame attempt at recreating 'The Girl From Ipanema.' We'd actually tried to turn that into a rock song back when we were making 'There Is Nothing Left to Lose', and it just sounded completely ludicrous. There was no way it would work.

There is a definite California country-rock vibe to some of the tunes on the acoustic disc, particularly 'Cold Day In The Sun'.

That is Mr Taylor Hawkins territory! He's all about the California country-rock.

Actually, 'Cold Day in the Sun' sounds like a young Rod Stewart sitting in with the Eagles.

Yup. That's Taylor's thing. For the record, I hate the Eagles [laughs]. No I don't hate them, but when I listen to The Eagles I think of three things: afros, cocaine, and ferns. I picture someone coming home after work and sitting down in a wicker chair on the porch with a glass of chardonnay. That California country rock thing is so brown to me. I don't get it.

Let's talk about your acoustic guitar work on the new album. When playing electric you often incorporate ringing open strings into fretted chords to create drones and extended voicings. That stylistic device lends itself well to the acoustic, and you use it to great effect on In Your Honor.

I think that comes from listening to a lot of Alex Lifeson when I was a kid. As a drummer, I know that I should say Rush belongs to Neil Peart, but I kinda feel like Alex is the badass in that band. And using open notes in conjunction with fretted notes was a big thing with him. I love that sound, and it's probably even more noticeable on the acoustic record, if only because the guitars aren't drowned in cymbals and distortion.

What acoustics did you use in the studio?

There was an old Silvertone that our producer, Nick Raskulinecz, had kicking around in his van for the last 12 years. The thing looked like a fucking cello! We used an old Gibson Country Western on a lot of the stuff, as well as some newer Gibsons, including a cutaway model. And we had a Seventies-era Martin that I bought in London a while back. It's a beautiful guitar. I saw it and had to have it.

The character of the acoustics comes through very clearly on the record. You can even hear the sound of the pick strumming across the strings.

Yeah, we were really into that. On things like 'Over and Out,' you can hear my fingers scraping against the strings as I move around the neck. And at first we were worried about that. I said, "Should I rub a stick of butter on this thing? It's making so much noise." But everyone said, "No man, it sounds great." It sounds like someone just sitting in front of a microphone playing a guitar.

What was the setup in the studio?

It was real simple. There wasn't a lot of mucking up the signal path. We'd put a Neumann microphone in front of the guitar and then run that into a Martech mic preamp, into the Neve or the API board and straight to tape. For some of the stuff there was just one mic on the guitar, but for a song like 'Razor,' for instance, I had a microphone set up behind me and pointed at my neck, another one in front of my face, a third pointed at the bridge of the guitar and then three or four mics scattered around to capture the sound of the room. The record was mixed by Elliot Scheiner, who's worked with some major bands like Fleetwood Mac and Steely Dan, and he called us up a few days after we gave him the album and said, "You guys, this is a serious fucking record. The tones are so natural and beautiful." And we were like, "Really? Great!"

It sounds like the album has exceeded your expectations.

I think this might be the first time in my life where I opened my big mouth, said I was going to do something and then actually did it. Usually I shut up and don't say anything for fear that I won't follow through. This time I challenged myself and the band by saying, "Okay, hey, we're old, and this is what we're going to do. It's gonna be great." And I knew that we couldn't walk out of that studio until it was exactly what we'd bragged it to be.

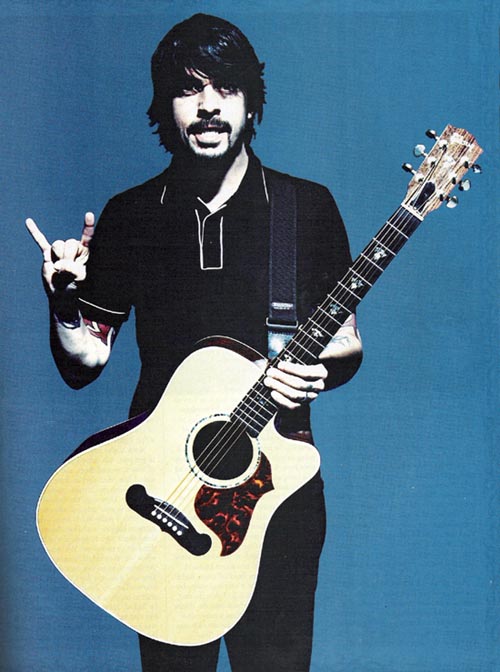

has proven Grohl to be not only a skilled

musician, but a first-rate songwriter as well.

Foo tunes like 'I'll Stick Around,' 'Monkey

Wrench' and 'All My Life' showcase both Grohl's ability to compose melodically inventive riffs and chord progressions as well as what appears to be an endless supply of memorable pop-rock hooks.

has proven Grohl to be not only a skilled

musician, but a first-rate songwriter as well.

Foo tunes like 'I'll Stick Around,' 'Monkey

Wrench' and 'All My Life' showcase both Grohl's ability to compose melodically inventive riffs and chord progressions as well as what appears to be an endless supply of memorable pop-rock hooks.