'I've never gotten off on chaos'

The Guardian

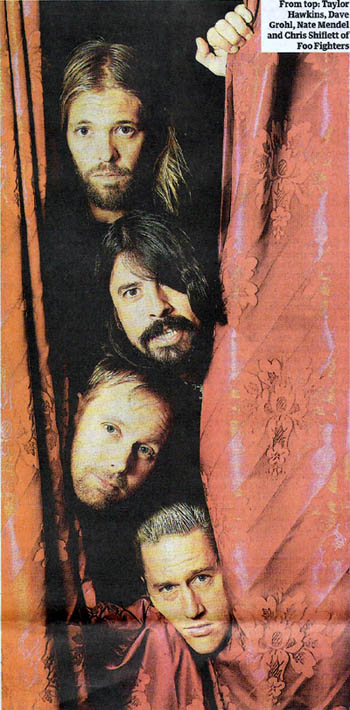

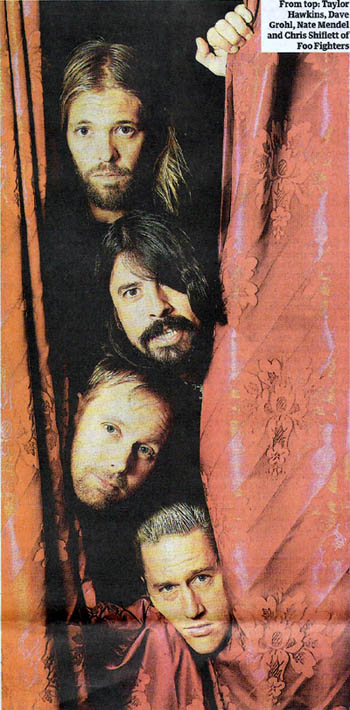

Foo Fighter Dave Grohl talks to Keith Cameron about what kept him alive and kicking after the death of Kurt Cobain and Nirvana.

The Dalmacia hotel in Hammersmith, west London, is clean but frills-free. That it can offer competitively priced triple rooms means its clientele sometimes includes rock bands with budgets on the threadbare end of shoestring. In October 1990, that meant Nirvana, who had arrived in London from Seattle without a record deal but with a wide-eyed new drummer whose powerhouse style would help propel them to global fame in little more than 12 months.

The Dalmacia hotel in Hammersmith, west London, is clean but frills-free. That it can offer competitively priced triple rooms means its clientele sometimes includes rock bands with budgets on the threadbare end of shoestring. In October 1990, that meant Nirvana, who had arrived in London from Seattle without a record deal but with a wide-eyed new drummer whose powerhouse style would help propel them to global fame in little more than 12 months.

To Dave Grohl, at 21 already a veteran of European squat tours with his previous band Scream, the Dalmacia seemed the height of luxury. "I loved that place," he says. "That's where I discovered English breakfast tea. I didn't realise it had caffeine in it. After seven cups I thought I was going to have a heart attack."

Seventeen years later, as leader of Foo Fighters, Grohl patronises rather more exclusive establishments when he comes to London - such as the Covent Garden hotel, where the loft suite costs five quid shy of a grand per night, enough to have fed and clothed the Grohl of old for a year or more. Not that he dresses like a multimillionaire now: the black sweatshirt, skinny jeans and Vans trainers suggest a man for whom conspicuous displays of rock-star largesse hold little attraction. Slouched on a sofa in a basement function suite, deferring jetlag with coffee and Parliament cigarettes, Grohl claims his massive wealth, accrued from both his tenure as Nirvana's drummer and the leader of the Foo Fighters, remains largely untouched. He owns a house in suburban Los Angeles ("relatively modest - which still means it's a mansion"), a car, a motorcycle and a recording studio. The latter he regards as his biggest extravagance, though a more telling investment was the house he bought for his mother so that she could relocate from the family homestead in Springfield, Virginia, and live just a mile or so away from Grohl, his wife Jordyn and their 18-month-old daughter Violet Maye.

Grohl's parents divorced when he was six. Though such trauma is often the catalyst for artistic turbulence and personal dissolution - Kurt Cobain being an acute example - in his case, it appears to have impelled him towards the protective certainties of family life. "For the past 20 years when I've been touring, I've always craved stability," he says. "I've never gotten off on chaos. Throughout the whole Nirvana experience I retreated to Virginia whenever I felt sucked into the tornado of insanity. Same thing with the Foo Fighters - I wouldn't be able to do this if I didn't have my feet planted firmly on the ground. So Jordyn and Violet are anchors that keep me from completely disappearing."

Following Cobain's death in April 1994, none of the smart money was on either of the other two members of Nirvana surpassing the commercial success of their previous band. Hoary prejudices regarding the musical competence of drummers mean damnation with faint praise has been the Foo Fighters' lot ever since their 1995 debut album minted the band's enduring template: an unashamedly populist twist on the punk/classic rock hybrid that Nirvana's success catapulted into the mainstream. The phrase "Grunge Ringo" entered the critical lexicon.

Following Cobain's death in April 1994, none of the smart money was on either of the other two members of Nirvana surpassing the commercial success of their previous band. Hoary prejudices regarding the musical competence of drummers mean damnation with faint praise has been the Foo Fighters' lot ever since their 1995 debut album minted the band's enduring template: an unashamedly populist twist on the punk/classic rock hybrid that Nirvana's success catapulted into the mainstream. The phrase "Grunge Ringo" entered the critical lexicon.

On the eve of the release of Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace, the sixth Foo Fighters album, Grohl reflects upon the fuss with a vindicated shrug. "I can understand how some people might resent me for having the audacity to continue playing music, but it'd take a lot more than that to stop me from doing it. I started Foo Fighters because I didn't want to retreat. Kurt dying shocked me into running away from music for a while. I couldn't imagine joining another band and sitting behind the drum set, because I would always think about Krist [Novoselic] and Kurt."

During 2002, Grohl played drums in public for the first time since Nirvana when he joined Queens of the Stone Age on tour. On his drum kit he stuck a photograph of Nirvana bassist Novoselic, his friend and ally in the bitter legal battle with Cobain's widow Courtney Love over who owned the rights to Nirvana's music. It also served as a reminder of how their careers had diverged in the wake of Nirvana. While Novoselic remained on the margins during his forgettable subsequent musical exploits in Sweet 75 and Eyes Adrift, Grohl became, however reluctantly, an ambassador for Nirvana - a living link to a group whose posthumous legacy was swiftly mythologised and laden with contention. The Foo Fighters' appearance at the 1995 Reading festival caused a near riot, when the second stage was inundated by people desperate just to see someone who'd been in Nirvana.

"Those first couple of years of the Foo Fighters when I stood there singing songs and saw kids wearing Nirvana T-shirts, I looked at it as a good thing," says Grohl. "Like it was almost support, for me. I didn't want to spend the rest of my life looking in the fucking rear view mirror and thinking about what could have happened or what should have happened, or how tragic the ending of the band was. I've always considered myself an optimist, I don't have a lot of regrets. I have a few, but ..." He falters as his flow takes him back to Cobain's exit, the declared low-point of his life. "Well," he sighs, "what a way to go."

The violence of Cobain's death, and the fact that it left so many questions unanswered, meant that a new record by a former member of Nirvana would inevitably be scrutinised for insights, opinions, even clues. Grohl's refusal to join such debates was actually undermined by his early lyrics' equivocacy; he denied that I'll Stick Around was directed at Courtney Love, but such lines as "How could it be I'm the only one who sees your rehearsed insanity" were grist to the conspiracy theorists' mill. Today, Grohl persists with erring on the side of enigma, acknowledging that many people will assume the song Let It Die on the new Foo Fighters album ("A simple man and his blushing bride/ Intravenous, intertwined") is about Kurt and Courtney.

"[It's] a song that's written about feeling helpless to someone else's demise," he states. "I've seen people lose it all to drugs and heartbreak and death. It's happened more than once in my life, but the one that's most noted is Kurt. And there are a lot of people that I've been angry with in my life, but the one that's most noted is Courtney. So it's pretty obvious to me that those correlations are gonna pop up every now and again." He laughs. "I still remain a little secretive about it all."

The barometer of popular perception puts Grohl's personality somewhere in between Gandhi and a Care Bear: he's frequently described in print as "the nicest man in rock". Evidence to the contrary is confined to the occasional ungentlemanly outburst at Courtney Love ("Ugly fucking bitch," he declared on-stage in 2002, an instance of plain speaking worthy of Love herself, who subsequently said of Grohl: "He's been taking money from my child for years") and the admitted infidelities that led to his divorce from first wife Jennifer Youngblood in 1997. The latter caused the departure from the Foo Fighters ranks of Pat Smear, latterly Nirvana's auxiliary guitarist and a close friend of Youngblood (Smear and Grohl were eventually reconciled, with the former rejoining the Foo Fighters for an acoustic tour in 2006).

Nor was Smear the first or last to go. Original drummer William Goldsmith left during sessions for 1997's album The Colour and the Shape, intimidated at having to play drums in a band led by one of the great rock drummers, and Smear's successor, Franz Stahl, exited before the recording of 1999's Grammy-winning There is Nothing Left to Lose. Only Grohl and bassist Nate Mendel remain from the original line-up, yet Grohl refutes the notion of himself as a dictatorial leader and of the Foo Fighters as merely a brand into which anyone could fit so long as they could rock hard and agreed with whatever he said.

"It's been eight years since anyone entered or left. And I had never asked anyone to leave, I had always begged people to stay when they wanted to leave," he says. "When William split I flew to Seattle to say, 'Are you sure?' With Pat, I was on my knees crying, saying 'Please don't go.' And he said, 'I just have to.' With Franz, it was purely musical and it was heartbreaking - I'd known him since I was 18. I pride myself on loyalty to everyone, from the people in the road crew to my family. That's a big part of my life: keeping those relationships intact." On cue, the phone rings, his wife calling to give him an update on Violet's latest malady: "How's her snots? She doesn't have a fever, does she? Oh, good. I'm doing an interview, can I call you in an hour? I love you ..."

If anything, Grohl's cast-iron civility and the detail of his previous employment have served to undercut his band's achievements: as if the Foo Fighters wouldn't enjoy such exalted levels of popularity, or be capable of such coups as their show-stealing Wembley Live Earth concert appearance, without that Dave dude's friendly smile and his former proximity to Kurt Cobain. He admits that such insinuation used to bother him. But 18 months' worth of early morning nappy calls have offered a fresh perspective on what really matters.

"No more than two weeks out on the road, that's the new rule. No more six months. Violet's the light at the end of the tunnel. And everything benefits. Musically I'm in a place I've never been 'cos there's no fear, I'm not afraid to write anything any more. A lot of that has to do with the big picture - having a child and realising that life's too short to be afraid of a fucking piano ballad."

Words: Keith Cameron

back to the features index

Following Cobain's death in April 1994, none of the smart money was on either of the other two members of Nirvana surpassing the commercial success of their previous band. Hoary prejudices regarding the musical competence of drummers mean damnation with faint praise has been the Foo Fighters' lot ever since their 1995 debut album minted the band's enduring template: an unashamedly populist twist on the punk/classic rock hybrid that Nirvana's success catapulted into the mainstream. The phrase "Grunge Ringo" entered the critical lexicon.

Following Cobain's death in April 1994, none of the smart money was on either of the other two members of Nirvana surpassing the commercial success of their previous band. Hoary prejudices regarding the musical competence of drummers mean damnation with faint praise has been the Foo Fighters' lot ever since their 1995 debut album minted the band's enduring template: an unashamedly populist twist on the punk/classic rock hybrid that Nirvana's success catapulted into the mainstream. The phrase "Grunge Ringo" entered the critical lexicon. The Dalmacia hotel in Hammersmith, west London, is clean but frills-free. That it can offer competitively priced triple rooms means its clientele sometimes includes rock bands with budgets on the threadbare end of shoestring. In October 1990, that meant Nirvana, who had arrived in London from Seattle without a record deal but with a wide-eyed new drummer whose powerhouse style would help propel them to global fame in little more than 12 months.

The Dalmacia hotel in Hammersmith, west London, is clean but frills-free. That it can offer competitively priced triple rooms means its clientele sometimes includes rock bands with budgets on the threadbare end of shoestring. In October 1990, that meant Nirvana, who had arrived in London from Seattle without a record deal but with a wide-eyed new drummer whose powerhouse style would help propel them to global fame in little more than 12 months.