Dazed & Confused

The two legends come together to worship at the altar of Sound City Ė LAís greatest, dirtiest, most rockíníroll studio.

When Nirvana pulled into the parking lot of Sound City in May 1991, they couldnít exactly remember how they had chosen this crumbling recording studio nestled deep in the beige dystopia of Van Nuys, Los Angeles. A couple of things struck them immediately about the former Vox amp factory: one, theyíd played in dive bars that looked cleaner; and two, the fumes from the Budweiser brewery down the street made them gag every time they inhaled. But reason prevailed: if it was good enough for Fleetwood Mac, the Grateful Dead and Neil Young, it was good enough for them.

Sixteen days later, the three Seattle punks piled back into their van for the long drive home. They didnít know it then of course, but within six months the Nevermind sessions would ignite a global youth revolution and go on to sell an estimated 40 million copies. The album would also reverse the fortunes of Sound City, which went from the verge of bankruptcy to being overrun with bands like Rage Against the Machine, Tool and Weezer, each keen to take a sip from the grungy golden chalice.

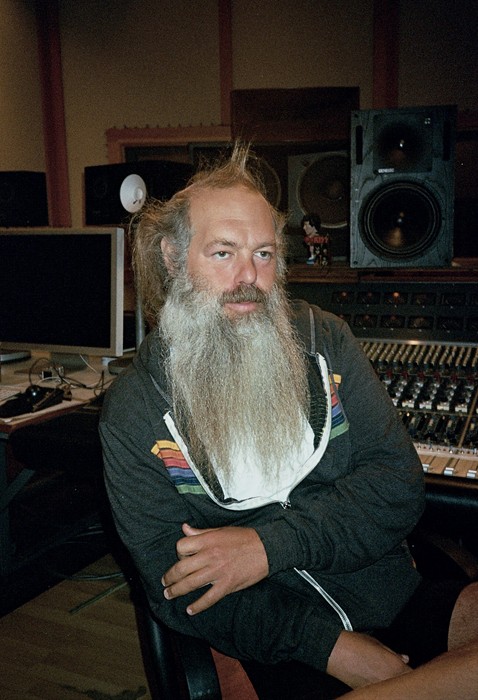

Three years on, Rick Rubin made the 15-mile drive from his Hollywood chateau to the Sound City stronghold. The Def Jam co-founder was already firmly established as the producer of his generation, thanks to sonic skirmishes with Slayer, Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but he had never experienced this particular studioís grimy charms for himself. After conquering his fear of sitting down on the crusty furniture, the 31-year-old bearded guru fired up the vintage Neve 8028 console, gave southern rock royalty Tom Petty the thumbs-up and pressed record. It kickstarted a relationship with the accidental hit-factory that would see him return time and time again to craft jams with titans such as Johnny Cash, Metallica and the Chili Pepper crew.

In 2011, when Sound Cityís owners finally surrendered to the Pro Tools revolution, they had no option but to sell off their vintage analogue equipment. Dave Grohl, whose nostalgic emotional attachment to Rupert Neveís sound desk overrode any professional concerns about the amount of archaic cocaine clogging up its faders, decided to take the console off their hands. More than just a token gesture, it galvanised him to direct Sound City, a feature-length documentary about the studioís history that in turn inspired Real to Reel, an allstar tribute album featuring Stevie Nicks, Trent Reznor, Josh Homme, Lee Ving and other assorted alumni.

A few days before Grohlís cinematic debut premiered in Hollywood Boulevard, Rick Rubin, one of the filmís most enlightening interviewees, made a rare pilgrimage back up the 405 Freeway to reminisce with the former Nirvana drummer about LAís unintentional musical mecca. Turning the lights down low in the control room of Grohlís Studio 606, the two friends sat once more in front of the coveted Neve 8028 and invited Dazed to pull up a pew...

Dazed & Confused: Mick Fleetwood describes Sound City as 'a church'. How would you both describe it?

Rick Rubin: I spent a lot of time there. I wouldnít describe it as a church. We had spiritual things happen, but it was really not a nice place to be. It was filthy. It felt like it didnít have to be that bad. It almost seemed like you had to really be an edgy person to let it be like that. It was like, how do we make it more funky?

Dave Grohl: When Mick Fleetwood first went there it was state of the art... in 1973. They had just built it, and had this new brown carpet and a new couch, so he was like, ĎIt was great.í Thatís why they decided to make a record there. The further you go down the line, the more peopleís first impressions turned into exactly what we experienced. The owners made a million dollars from producing the Rick Springfield record, but when you watch the film youíre like, ĎWhere the fuck did all that money go? What the fuck did you do with that? You didnít even paint the fucking walls!í When Nirvana first got there, they were really close to closing down. They had a manager that was dealing drugs and nobody knew what the fuck was going on. It was cheap though.

D&C: Were the owners scared to change anything in case it ruined the sound?

DG: No one was going to re-floor the room, because everyone was afraid that they would lose what was awesome about Sound City. It might also be total neglect.

RR: It looked like neglect. In places where the sound didnít matter, say the bathrooms, there were 20 sockets for light bulbs. And I donít remember at any point more than, like, three light bulbs in those 20 sockets. That had nothing to do with the sound in the studio. (laughs)

DG: I always felt like it was a specific type of person that went to Sound City. And because of that, there was something specific that it represented. You wouldnít go there and find fucking Lady Gaga making a record. You would find a band like Rage Against the Machine. We found a video of them making (their self-titled debut) in there with a bunch of their friends watching them. In the film we go from the audio of the album and fade into the audio from the one mic on the video camera and itís the same fucking take. That rawness was exactly what Sound City was about.

D&C: Do you think that its griminess also helped to ground the egos of the world's biggest rock stars?

RR: I think everyone was willing to put up with being at Sound City because of how good it sounded. Itís a hard thing to find, really; where you can set up in a room and have it sound like how you sound. Someone said that it was because it was so poorly built. The studio didnít add anything to the sound. It was like a barn. It wasnít built to studio standards. Itís just sort of a big, empty space that was flimsy enough that it didnít really contain the sound. So it allowed the music to breathe. It wasnít on purpose.

DG: A block away thereís a Best Western hotel next to a Taco Bell. When Metallica made an album there, James Hetfield stayed at the Best Western. James fucking Hetfield stayed at that fucking shithole hotel so that he could be two blocks away from the best-sounding room in the fucking world, you know. People go to great lengths. My studio, where we are now, might be the only one thatís farther out.

RR: Unless you were going to Sound City you would never go to this place, this area. Itís in the middle of nowhere.

DG: I live nearby, but thatís the only reason I have my studio here. Otherwise you wouldnít come to the Valley. But thereís something to be said for working in studios that arenít in the middle of everything. Iíve never made an album in New York City. I canít even imagine turning off the world and walking into a room knowing that on the other side of that wall is Fifth Avenue. I like to be somewhere where Iím a little bit isolated. I donít need to go to fucking Hawaii to make a record. That wasnít one of the things I did like about Sound City: I felt like once I was there I had to work because I couldnít go take a break. It almost amplified that work ethic because, what are you gonna do? Hang out there all day long? Not really.

RR: Absolutely. It was a place to come, do your work and get out as quickly as possible. Another part of it that drew us in was the equipment. As technology continued, in theory, to improve, things kept changing and the changes werenít always for the better. And it didnít always suit rockíníroll, which was more often than not what we were recording. So it was hard to find studios that were more traditional. It wasnít really production; it was about documenting a moment. Sound City was a really great place to document a moment.

DG: The first song we recorded there was ĎIn Bloomí. We set up, tuned up and got big sounds. Iíd never heard my drums sound like that before. It was the first time weíd heard Nirvana sound like that. It didnít sound like Bleach, you know. It didnít sound like the Peel sessions weíd done. It didnít sound like any of the demos. It sounded like Nevermind. And when I heard the toms, the kick and the snare on ĎIn Bloomí Ė it was an instrumental take, I donít even know if Kurt did a guide vocal Ė our jaws dropped, because it sounded real, it sounded aggressive, it sounded really powerful. After what first day we knew it was gonna be alright. We blew through everything in 16 days. That made the greatest impression on me.

RR: Sound City had such a limited amount of gear that there wasnít much opportunity to change the way anything sounded. It was pretty much limited to microphones and this Neve console, which, luckily, doesnít change stuff much. You donít really have an option but to sound like what you sound like.

DG: Thereís a really great quote from (Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers guitarist) Benmont Tench in the movie where he says, ĎItís cruel, because youíd go to the control room and listen to yourself and just think ďI suckĒ, which pushed you to be betterí That was a good thing.

D&C: When you have one of those days when you suck, how do you get over it?

DG: I canít even imagine your job, Rick! When I go in to record something, Iíll do it until I get it. I have a hard time walking away from things, so if Iím trying to get it, I might want to throw something through a fucking window but I work hard until I get it. Iíll sit there and look at whoever is producing us and I feel so sorry for them ícause I know they just want to take my hands and make them do what they need to do.

RR: I just have a lot of patience. You have to, becausewhat weíre looking for isnít in anyoneís control. Itís like everyoneís there with the same intention to make this great thing happen but none of us can make that great thing happen. The closest comparison I can make to it would be fishing. When you go fishing you could fish all day and not catch anything, but you have a much better chance of catching fish if youíre fishing all day than if youíre not fishing all day. Some days weíll play it three times, and itís all great. Sometimes weíll play it 100 times and it never gets great. Waiting is kind of the job.

DG: A lot of musicians get red-light fever; they get scared.

RR: It's anxiety. †

DG: You could sit through a song and do a perfect rehearsal, and then hit record and everything changes.

RR: Stage fright.

DG: When we were kids and we knew someone with a studio that had a reel of tape, you couldnít wait to get over there to record something. You werenít afraid to hit record when you were 16. It was like, ĎFuck, weíre gonna record, this is amazing. I get to record a song.í I still feel the same way.

RR: Usually when I start a new project thereís a fear of the unknown; maybe itís a band Iíve never been in the studio with before.People are so different. Itís almost like you need to go through the process, discover and unlock what it is that makes that band that band. And a lot of times they donít know it. More often than not they donít know it. But over time you start seeing patterns of things that work and donít work and why. It does seem like the more prepared you are before you go into the studio, the better the experience. If the band really knows what theyíre doing, you save a great deal of time. The idea of going into a studio to write an album seems like a bad idea. Youíre never focused on getting a great performance because youíre still trying to figure out what youíre going to do.

D&C: On the flipside, someone like Jay-Z has it all in his head. It must be amazing to witness, but as a producer you can't really prepare for that, can you?

RR: Itís about getting the music right, and then that inspires him to do the vocals. Heíll sit back in the corner and heíll play the track over and over and over again, probably for a half hour, 45 minutes, an hour Ė almost to the point where you donít even realise heís there. Itís just like this monotonous thing going on, and then all of a sudden he jumps up and heís like, ĎI got it,í and he runs in the other room and does a complicated verse. Itís really unbelievable. And then heíll do it, and then heíll do it again and itíll be different. The words will be pretty much the same but the phrasing will be different and the accents will be different. Imagine that youíve written a solo and then you play it, like, different ways; thatís kind of what he does with his vocals. Unbelievable.

D&C: Rick, you have a stuffed bison in your home studio. Whatís the weirdest thing youíve both encountered in other studios?

RR: This guy called Alan (Dickson) from Grandmaster in Hollywood.

RR: This guy called Alan (Dickson) from Grandmaster in Hollywood.

DG: (laughs) I remember walking into a studio at Grandmaster and it had a calendar up on the wall. It said ĎKorní on it, and they had just been in the studio for a week. I said, ĎWow, what did Korn record here?í And they said, ĎKorn didnít record here.í So I replied, ĎWhatís this youíve got on the fucking calendar then?í, and they said, ĎNo, thatís ďPornĒ. We film porn here.í All of a sudden I didnít want to touch anything. I saw one of the pornos, it was called Cum Bandits, a parody of Time Bandits. They had a bathtub in the studio which turned into a portal to another dimension. That was a little weird.

D&C: Do you think any babies have been made on this beloved Neve desk of yours?

DG: Dude, when we brought this over here, my poor friend Lou had to spend about a week going through this thing with a toothbrush just to get the cocaine and the fried chicken out of it. Fuck, yeah. Itís funny, I didnít want to modify the board. All I wanted to do was yank it out of there, plug it back in, and make sure that it was good to go. You get worried that the years of filth might have something to do with the way it sounds. Mike from the Heartbreakers emailed me to say, ĎOh, by the way, if you find any white powder in that board itís my medicine. Return it immediately.í (laughs)

RR: I canít even imagine how many things I spilled on this board. Have sex, drugs and RockíníRoll disappeared from todayís studio culture?

DG: No.

RR: Not for The Foo Fighters. (laughs) They fly the flag.

D&C: Rick, were you upset that Dave got his hands on SOUND CITYís Neve board?

RR: Not at all. Iím glad that he got it and a movie got to be made about Sound City because of it, which never would have happened if I had bought it. I already have a couple of similar boards. I was tempted but then felt like it would be a disservice because, as Dave says in the film, he knew that if he got it, it wouldnít sit bubble wrapped in storage somewhere, and if I did, it probably would. I have an extra Neve sitting up on its side in my garage, so this would be next to that and it would be doing a disservice to what this is.

DG: Itís one of the funny things about a board; you look at this board and it seems so archaic, considering what people use to make albums now. A lot of people consider it obsolete, but it still fucking works. This thing will probably work longer than Iíll be alive. In 30 or 40 years from now you will probably still be able to make an album on this board. And as much as it might seem impractical and it might seem obsolete, it still does what itís supposed to do.

RR: And it will probably sound better than anything new that comes out and replaces it.

DG: Things that try to emulate or simulate what this board does, you know, they are more practical and they are more accessible and if you canít fit one of these into your living room itís probably the closest thing youíre going to get. But still, what this does is what only this really does.

D&C: Do you think that the fabric of a studio Ė the building and equipment Ė hold a sound memory that affects subsequent recordings?

RR: For sure. How formal or how casual the space is can really influence everything. We recorded Johnny Cash in my living room. It couldnít have been more casual. And I feel like that lack of pressure creates a certain feeling, and the same Iím sure is true with concerts. If you do a concert in the middle of nowhere and thatís one gig, and the next night youíre playing at Madison Square Garden...

DG: Itís different.

RR: ...because itís Madison Square Garden. The Royal Albert Hall is different to playing somewhere in the Midlands. Even if itís just your perception of it, everything changes.

DG: I really believe that the experience of making an album influences the end result. On our second Foo Fighters album I was going through a fucking divorce, I was living in my friendís back room, getting pissed on at night by his fucking dog, in a sleeping bag, and I would go to the studio and write a song that was so fucking heartbreaking that I canít even listen to some of that music because it brings me back to how miserable I was. So that experience totally influenced that album.

†

RR: Plus the fact that it was recorded at Grandmaster (laughs)

DG: (laughs) That definitely influenced a lot of shit in itself. Whether itís the history of a room, or whether itís the ghosts in the fucking room, whatever you choose to believe, if you want to capture a moment, something real, then you just have to be open to everything.

D&C: Whoís made you BOTH step up your game in the studio?

DG: Itís hard to top Paul McCartney. When Paul comes in to your studio and heís brought his Hofner bass, ĎThe Bassí, and heís brought his Les Paul, ĎThe Les Paulí, and a guitar made out of a cigar box, and he decides to play the guitar made out of the cigar box, you realise, ĎThatís badass. I have to be badass, too. I canít just play it like Iím playing with my friends down the street. I have to be great right now.í Iím lucky, Iíve jammed with some crazy fucking wicked musicians.

RR: Iíve gotten to work with amazing people. I would say usually we get to a point before we get into the studio where there isnít that sense of anxiety or nervousness of who they are because I donít think it would be as productive in the studio if that was the case. But maybe meeting someone like Neil Young for the first time made me anxious. But then when you get to hang out with Neil Young itís all good. We were supposed to record together and then he cut off a piece of his finger and couldnít play guitar. But he still had the studio booked, so we went in and played this harmonica through his guitar amp...

DG: Rad!

RR: Yep.

Words: Tim Noakes Pics: John Kilar