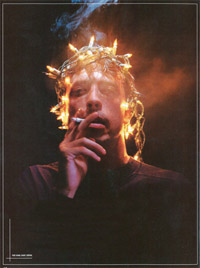

It's Thursday late night at Junior's Sky Bar, high atop Hollywood's Sunset Marquis hotel, and Dave Grohl has just ordered his sixth Patron tequila. It's the only way to handle the scene. At a table in the corner, Elliott Smith and Foo Fighters drummer Taylor Hawkins are battling for the attention of Minnie Driver. Charlize Theron and Third Eye Blind's Stephan Jenkins are engaging in a way-too-conspicuous display of public affection at the bar, as Winona Ryder looks on enviously. Grohl rolls his eyes, lights a cigarette, and calls for another drink. He mumbles something to himself about getting out of Los Angeles, about returning home to Virginia, where maybe he belongs.

Now with apologies to Ronald Reagan biographer Edmund Morris, who bizarrely inserted himself into the former president's Hollywood days to understand decisions made when he wasn't there, that scene's part fact and part speculation. What's true is this: After almost two years in Los Angeles, after too many enjoyable lost evenings led to tired, dark nights of the heart, Grohl felt himself immersed in Hollywood celebrity and losing the thread of his soul.

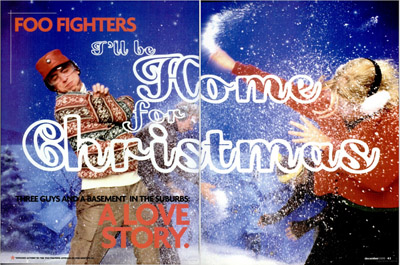

So Grohl traded the Viper Room for Chili's. He swapped movie-star hideaways for backyard barbecues. He moved from Los Angeles back home to Alexandria, Virginia, bought a house in a tree-lined suburban subdivision not far from historical Old Town and installed a basement studio. There, amidst the cul-de-sacs and chain restaurants, the Foo Fighters spent the cold months of early 1999 losing a bandmate, searching for a new record deal, and finding themselves again.

Then they documented those difficult months, and ultimately, broke through with what Grohl sees as his most prolonged period of creativity and clarity yet, the Foo Fighters aptly-named third album, There Is Nothing Left To Lose. Indeed, Grohl admits over brunch at New York's SoHo Grand hotel, had he stayed in LA any longer, there might not have been anything worthwhile left to lose.

"I could see myself losing the point," Grohl says. "I went through my tequila phase. I had friends who worked at the Viper Room, so I could drink for free there. When we were mixing the Verbena record, we stayed at the Sunset Marquis and Junior's Sky Bar - there is the biggest scene. I went down there a couple nights and got pretty hammered. But there's something about that kind of bar where famous people feel safe that makes me sad. It makes me angry that someone would consider themselves so wanted that they feel they need refuge at a celebrity bar. It's gross."

"I could see myself losing the point," Grohl says. "I went through my tequila phase. I had friends who worked at the Viper Room, so I could drink for free there. When we were mixing the Verbena record, we stayed at the Sunset Marquis and Junior's Sky Bar - there is the biggest scene. I went down there a couple nights and got pretty hammered. But there's something about that kind of bar where famous people feel safe that makes me sad. It makes me angry that someone would consider themselves so wanted that they feel they need refuge at a celebrity bar. It's gross."

"This album has so much to do with my disdain of Hollywood, and the glorification of California's glamorous life. I did enjoy it," Grohl admits, with a slight grin. "But I thought it was fucking disgusting. Now I'm sure everybody there is very nice. But everybody who lives there also says, 'I hate Los Angeles. I'm getting out as soon as fill-in-the-blank.' Only, most people who move there stay because they want to do Hollywood things, which you can't do in Virginia, or other normal places. I wanted normalcy. I just felt like I had to go back to Virginia."

Grohl thought about buying a farm. He had dreams of growing Christmas trees that he could sell at gas stations throughout Virginia. Then he decided farming might be too much responsibility, and started shopping for a house in the suburbs of Washington, DC not far from where he spent his childhood, and where he learned about punk rock from the straight-edge, DC hardcore scene based around Dischord, Minor Threat, and all-ages matinee shows.

It seemed like the natural place to start over. Grohl had only moved to Los Angeles after a painful divorce from his wife, Jennifer, made Seattle seem way too small, but he didn't find any of his answers under the warm California sun. The Foo Fighters no longer had a record deal, as a key-man clause in their contract with Capitol allowed the band out of the agreement if then head honcho Gary Gersh were to leave the label. So when Gersh departed, Grohl decided to walk as well. Alone and label-less, Grohl and pal Adam Kasper started building a basement studio.

"That was the whole point: having no label, having your own studio, and not negotiating with anyone. We wanted to do it ourselves," says Grohl. "The whole time we were making the record, it was just the three of us and Kasper in the basement for four months. It was great. It was so much fun."

Grohl hadn't recorded so simply and freely since making demos under the name Pocketwatch in 1989 that, ironically, formed the basis of the first Foo Fighters album. But before that freedom was possible, the band had to experience some turmoil. Grohl's longtime friend Franz Stahl, his Scream bandmate as a punk rock DC teen more than a decade before, joined the band in 1997 when Pat Smear quit on the heels of a major European tour. Except when the four of them tried to demo songs together in Grohl's basement starting last February, things were not clicking as a four-piece with Stahl.

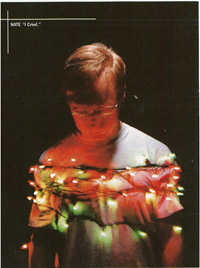

"We were just going in two different directions musically, and the three of us had made a connection that we had never done before," says Grohl. "It sucked. I love Franz, and I miss him. But the three of us were moving at pace and doing something we've never done. Nate and I were making this connection where he was complementing everything that I came up with. Taylor was so amped to go that he was playing like a madman. Our enthusiasm was really huge, and it seemed like most of the creative energy was coming from right here."

"We were just going in two different directions musically, and the three of us had made a connection that we had never done before," says Grohl. "It sucked. I love Franz, and I miss him. But the three of us were moving at pace and doing something we've never done. Nate and I were making this connection where he was complementing everything that I came up with. Taylor was so amped to go that he was playing like a madman. Our enthusiasm was really huge, and it seemed like most of the creative energy was coming from right here."

It was, Grohl says, an entirely different experience than making any other Foo Fighters record. The first one was essentially just Grohl and producer-pal Barrett Jones. The second album coincided with drummer William Goldsmith's meltdown and turmoil in Grohl's personal life. There were also major issues with Pat Smear, even though, at the time, Grohl credited Smear's guitar work for opening up his songs in ways he could never have imagined.

"(Grohl) was just kissing his ass so he'd stay in the band," Hawkins says of the Smear situation. "Now we're glad he's gone. Hey, how're you doing Patty?"

"Oops," says Grohl. "We were between a rock and a hard place then. We were under his thumb. There are some songs he didn't even play on on that record."

More bothersome were pressures, both internal and external, to make a perfect-sounding record that would produce radio hits.

"The last album was the conventional rock recording method. Find a producer. Play the demos. Do pre-production. Go into the studio. Perfect everything. Go to mix. Make it perfect," says Grohl. "This record was: Try to build a studio in your basement. Try to make it as perfect as you can before you get tired of trying to make it perfect. Settle for the best you can do. There's no way that you could have a more relaxed recording environment. There's no label. There's no clock. We had no deadline. Once we finished our record, we said to labels. 'Here it is. Do you want it?' We had nothing left to lose. That's what you're getting on this album."

Grohl, who worries that his lyrics were too love letter-esque and emotionally obvious on the slick sounding The Colour And The Shape, revels in the imperfections of There Is Nothing Left To Lose.

"We made it a point to stay away from computers or ProTools," says Grohl. "It was important to me to make sure we got performances that were flawed in order to give them more personality. We spent time trying to get these songs right, but not just right. ProTools has become such a huge part of making an album and it seems to suck the life and soul out of songs especially on drums. It's awful.

"The legendary drummers - Keith Moon, John Bonham - were people who didn't have metronometime. You can hear in the songs that they didn't necessarily understand the arrangements as they were recording them.

Bonham was

famous for that. He would move into a chorus before it was there, and end up in the middle of it one bar later. It was great. Those performances are so memorable because they're human. They're not mechanical. Records sounded bigger because there were so many glitches, warts and imperfections that they were believable. Nowadays, radio has such a hard time with imperfection that we have to present the rock in its perfect form, and it just doesn't seem believable."

"The legendary drummers - Keith Moon, John Bonham - were people who didn't have metronometime. You can hear in the songs that they didn't necessarily understand the arrangements as they were recording them.

Bonham was

famous for that. He would move into a chorus before it was there, and end up in the middle of it one bar later. It was great. Those performances are so memorable because they're human. They're not mechanical. Records sounded bigger because there were so many glitches, warts and imperfections that they were believable. Nowadays, radio has such a hard time with imperfection that we have to present the rock in its perfect form, and it just doesn't seem believable."

That's hardly an issue on Nothing Left To Lose, which neatly blends the strengths of both records: the raw immediacy of Grohl's one-man-band debut, and the catchiness and emotionality of Colour And The Shape. "Stacked Actors" rages viscerally against LA's platinum blondes. But "Aurora" is perfectly formed pop with heart-tugging lines like "I kinda died for you/You just kind of stood there." fora Name cmd Me First and the Gimme Gimmes guitarist Chris Shiflett. "Headwires" offers a psychedelic reminiscence of acid, while "Ain't It The Life" broods somberly, and the album-ending "M.I.A." rages against all things superficial, all the while sounding like a rehearsal captured on tape. The freedom to experiment came from the freedom of the suburbs.

"It had everything to do with getting away from the industry, building a studio on our own, and making an album on our own," says Grohl. "We wanted to prove to ourselves that we could do it, so that we could feel like what we are doing is real. There are times when it doesn't feel like it was real. And that had everything to do with moving back to Virginia."

Grohl gets up to grab a smoke, which seems like a good time to ask Hawkins and Mendel how they enjoyed the wonders of the Virginia suburbs.

"Virginia is as boring as you could ever fucking want it to be," says Hawkins. "We went out twice the whole time we were there because there wasn't much to do. It was comfortable there, but there wasn't anything happening."

"The area where Dave lives is just all strip malls and residential areas. It's all Chili's and Black Eyed Peas," adds Mendel. "It was weird. It didn't feel like we were making a record to me. It was so casual. The studio was a shambles. The equipment all worked fine, but it never really got put together. Those guys did so much work to get to the point where it was operational that making it look like a studio was secondary."

For Mendel, the key to the Nothing Much To Lose wasn't so much swapping LA for Alexandria as it was losing Stahl.

For Mendel, the key to the Nothing Much To Lose wasn't so much swapping LA for Alexandria as it was losing Stahl.

"Franz leaving the band was a really traumatic experience for me. I cried after it happened," he said. "But we all went through it together, and I feel like it made us closer. Right before we went in to record we had this traumatic bonding experience that gave us cohesion. It sounds dorky, but there was a lot of hugging going on before we made this record." Mendel's been through many of those group-affirmation hugs as the last remaining original Foo Fighter. First his pal and Sunny Day Real Estate bandmate William Goldsmith cracked under the pressure of playing drums in Dave Grohl's band. Then Pat Smear took his brightly hued hair and bad attitude and went home, only to be replaced by the since-departed Stahl. Stahl's replacement, just in time for tour, is No Use for a Name and Me First and the Gimme Gimmes guitarist Chris Shiflett.

"With other bands, there's drug addiction and rehab. We just have people go," says Mendel.

"This band didn't have the luxury of not growing up in the public eye," Hawkins explains. "This band has been totally growing up in public, and growing up, and growing up."

"I don't know if people realize that when they make comments like, 'Why can't you guys keep any members?' It just doesn't come across people's minds," adds Mendel.

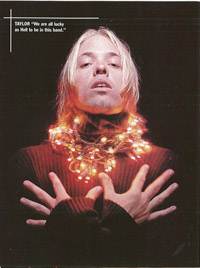

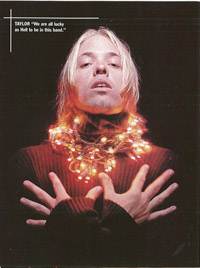

"Let it be known that it's not Dave putting that pressure on anyone." says Hawkins. "It's the kind of pressure anybody puts on themselves when they're up against something that's going to be hard. We all are lucky as hell to be in this band."

Grohl returns, curious about what's been discussed in his absence.

"Oh, you know," says Hawkins, in a teasing, singsong voice. "That Dave, he sure can't keep a band together."

"Well," cracks Grohl, "neither could Prince. He lost a band member every single."

"That's because he was probably a dick," Hawkins retorts. Grohl scratches his chin with a mock-ponderous pose. "Hmmm."

Perhaps the only thing Grohl's less concerned about than public perception that he can't control is the reception the latest Foo Fighters album will receive from modern rock radio programmers whose jobs, ultimately, were created by the Nirvana revolution.

Perhaps the only thing Grohl's less concerned about than public perception that he can't control is the reception the latest Foo Fighters album will receive from modern rock radio programmers whose jobs, ultimately, were created by the Nirvana revolution.

"If we were concerned about that kind of thing we probably would have made a slicker record, with computers, machines and two turntables and a microphone," Grohl says. "But we're not, so we didn't. I think what's going on, and one of the reasons why we don't necessarily fit into a lot of what's happening on the radio, is there's an absence of melody. It's more about the sounds than the songs. It's more about the dynamics than the arrangements. It's more about how huge a song can get rather than if it can go from point a to point b.

"A lot of songs nowadays are just built on super-basic caveman dynamics. Quiet. Creepy. Grrr! Loud. Quiet. Creepy. Grrr! Loud. Some of it's interesting, but it doesn't seem to challenge anything. No one seems to be challenging the listener anymore."

Grohl doesn't blame lazy programmers, novelty one-hit wonders or lame Nirvana rip-offs, as much as he does those artists who should know better. The problem, he suggests, springs from alt-rockers who have betrayed the roots of the '80s DIY scene that spawned '90s alt-rock by believing that they can become cartoonish rock stars capable of being rock-and-roll saviors. He's well aware that the Foo Fighters anti-California glamour album will be compared to Hole's Celebrity Skin, the in-love-with-it-all take on falling in love with Malibu and Fleetwood Mac that Cobain's widow Courtney Love released last year. "Yeah," Grohl agrees, then seems to address Love without ever mentioning her by name. "Things have gotten so desperate that all these artists have claimed that they're coming to save rock 'n' roll. That the world needs rock stars to save rock 'n' roll. When in reality, the world needs music to save rock 'n' roll. Everyone was kind of missing the point." "What these people were saying is, 'Kids need a super-hero fucking rock star to look up to and worship like a fucking cartoon character. because that's what rock is all about.' Sure in the '70s you had rock stars who were cartoon characters. Steven Tyler's lips, Mick Jagger's lips, Robert Plant's crotch. But they had music to back it up. "I'm surprised that a lot of the people who seem to have come from maybe the some punk rock background somewhere got it blurred. The rock star was more important than the music. The image was more important than the

music. The sound was more important than the song. I don't want to come off sounding like a songwriting genius, because I'm not. All I do is make songs we're capable of making. But all our focus is on that — not on anything else. People don't know what to believe in because they don't think anything's believable."

Indeed, what Grohl's identified is all part of the post-Nirvana fallout, part of the old boss/new boss cultural shift that put a modern rock station in every town but ensured that they'd play nothing but Third Eye Blind and the Goo Goo Dolls, and that allowed millions to hear Johnny Marr's scintillating guitar riff that opens the Smiths' "How Soon Is Now?" only as a Nissan ad.

Indeed, what Grohl's identified is all part of the post-Nirvana fallout, part of the old boss/new boss cultural shift that put a modern rock station in every town but ensured that they'd play nothing but Third Eye Blind and the Goo Goo Dolls, and that allowed millions to hear Johnny Marr's scintillating guitar riff that opens the Smiths' "How Soon Is Now?" only as a Nissan ad.

If Nirvana and Cobain kicked down that door, Cobain didn't like what he saw inside. His death presaged the mainstreaming of alternative but left the new youth culture Nirvana created leaderless, and with an authenticity void exceedingly vulnerable to being hijacked by whining one-hit dullards or superstar hype machines like Love. Would these issues exist if Cobain had lived to provide a different example?

"If he were around? I don't know. That's a weird question to answer," Grohl says. "But I still feel the same, if not angrier. I mean, when we were young, in the mid-'80s, we were singing and screaming about our hate for superficial things, right? I'm angrier now, probably more so than I was then. I don't think I could ever do the rock star thing. It would just be too strange. It seems like that movie Sybil. How on earth could you walk on stage and be someone else and not lose your fucking mind? How could you look in the mirror and see someone else?"

Now, looking at himself as a single suburbanite, with his acre-and-a-half Alexandria home, Grohl looks and the mirror and, for once, likes what he sees. He's a songwriter secure enough with himself to believe in his experiments, whose insecurities keep him humble and unassuming, and who draws out his thoughtful, introspective side simply without thinking about it too much.

"I think with the last record we were scared to do something like this because we still felt like we were supposed to be a hardcore band or a punk-rock band, or loud and crazy. At least I did. I wasn't comfortable enough as a vocalist or guitarist to dive into that yet," Grohl says. "One of the things about this record that I hear is we're comfortable doing those things. Before they might have sounded forced. They may have sounded like a garage band or a punk-rock band trying to write ballads and trying to pull them off.

"Now, it's just, 'Fuck it.' I don't give a shit. I know we can do it. The three of us can do fucking anything we want. We really can. We can do fucking Yes covers, or we can do an Angry Samoans cover. And that's what's wrong with rock 'n' roll. No one has that range anymore. I really believe we can make any kind of record that we want. We could go out and make a drum 'n' bass record. We could go make a metal record. For sure we could make a metal record! We could make a record way poppier than this if we wanted to. It's up to us to decide which direction we want to go in."

Now with apologies to Ronald Reagan biographer Edmund Morris, who bizarrely inserted himself into the former president's Hollywood days to understand decisions made when he wasn't there, that scene's part fact and part speculation. What's true is this: After almost two years in Los Angeles, after too many enjoyable lost evenings led to tired, dark nights of the heart, Grohl felt himself immersed in Hollywood celebrity and losing the thread of his soul.

So Grohl traded the Viper Room for Chili's. He swapped movie-star hideaways for backyard barbecues. He moved from Los Angeles back home to Alexandria, Virginia, bought a house in a tree-lined suburban subdivision not far from historical Old Town and installed a basement studio. There, amidst the cul-de-sacs and chain restaurants, the Foo Fighters spent the cold months of early 1999 losing a bandmate, searching for a new record deal, and finding themselves again.

Then they documented those difficult months, and ultimately, broke through with what Grohl sees as his most prolonged period of creativity and clarity yet, the Foo Fighters aptly-named third album, There Is Nothing Left To Lose. Indeed, Grohl admits over brunch at New York's SoHo Grand hotel, had he stayed in LA any longer, there might not have been anything worthwhile left to lose.

"I could see myself losing the point," Grohl says. "I went through my tequila phase. I had friends who worked at the Viper Room, so I could drink for free there. When we were mixing the Verbena record, we stayed at the Sunset Marquis and Junior's Sky Bar - there is the biggest scene. I went down there a couple nights and got pretty hammered. But there's something about that kind of bar where famous people feel safe that makes me sad. It makes me angry that someone would consider themselves so wanted that they feel they need refuge at a celebrity bar. It's gross."

"I could see myself losing the point," Grohl says. "I went through my tequila phase. I had friends who worked at the Viper Room, so I could drink for free there. When we were mixing the Verbena record, we stayed at the Sunset Marquis and Junior's Sky Bar - there is the biggest scene. I went down there a couple nights and got pretty hammered. But there's something about that kind of bar where famous people feel safe that makes me sad. It makes me angry that someone would consider themselves so wanted that they feel they need refuge at a celebrity bar. It's gross.""This album has so much to do with my disdain of Hollywood, and the glorification of California's glamorous life. I did enjoy it," Grohl admits, with a slight grin. "But I thought it was fucking disgusting. Now I'm sure everybody there is very nice. But everybody who lives there also says, 'I hate Los Angeles. I'm getting out as soon as fill-in-the-blank.' Only, most people who move there stay because they want to do Hollywood things, which you can't do in Virginia, or other normal places. I wanted normalcy. I just felt like I had to go back to Virginia."

Grohl thought about buying a farm. He had dreams of growing Christmas trees that he could sell at gas stations throughout Virginia. Then he decided farming might be too much responsibility, and started shopping for a house in the suburbs of Washington, DC not far from where he spent his childhood, and where he learned about punk rock from the straight-edge, DC hardcore scene based around Dischord, Minor Threat, and all-ages matinee shows.

It seemed like the natural place to start over. Grohl had only moved to Los Angeles after a painful divorce from his wife, Jennifer, made Seattle seem way too small, but he didn't find any of his answers under the warm California sun. The Foo Fighters no longer had a record deal, as a key-man clause in their contract with Capitol allowed the band out of the agreement if then head honcho Gary Gersh were to leave the label. So when Gersh departed, Grohl decided to walk as well. Alone and label-less, Grohl and pal Adam Kasper started building a basement studio.

"That was the whole point: having no label, having your own studio, and not negotiating with anyone. We wanted to do it ourselves," says Grohl. "The whole time we were making the record, it was just the three of us and Kasper in the basement for four months. It was great. It was so much fun."

Grohl hadn't recorded so simply and freely since making demos under the name Pocketwatch in 1989 that, ironically, formed the basis of the first Foo Fighters album. But before that freedom was possible, the band had to experience some turmoil. Grohl's longtime friend Franz Stahl, his Scream bandmate as a punk rock DC teen more than a decade before, joined the band in 1997 when Pat Smear quit on the heels of a major European tour. Except when the four of them tried to demo songs together in Grohl's basement starting last February, things were not clicking as a four-piece with Stahl.

"We were just going in two different directions musically, and the three of us had made a connection that we had never done before," says Grohl. "It sucked. I love Franz, and I miss him. But the three of us were moving at pace and doing something we've never done. Nate and I were making this connection where he was complementing everything that I came up with. Taylor was so amped to go that he was playing like a madman. Our enthusiasm was really huge, and it seemed like most of the creative energy was coming from right here."

"We were just going in two different directions musically, and the three of us had made a connection that we had never done before," says Grohl. "It sucked. I love Franz, and I miss him. But the three of us were moving at pace and doing something we've never done. Nate and I were making this connection where he was complementing everything that I came up with. Taylor was so amped to go that he was playing like a madman. Our enthusiasm was really huge, and it seemed like most of the creative energy was coming from right here."It was, Grohl says, an entirely different experience than making any other Foo Fighters record. The first one was essentially just Grohl and producer-pal Barrett Jones. The second album coincided with drummer William Goldsmith's meltdown and turmoil in Grohl's personal life. There were also major issues with Pat Smear, even though, at the time, Grohl credited Smear's guitar work for opening up his songs in ways he could never have imagined.

"(Grohl) was just kissing his ass so he'd stay in the band," Hawkins says of the Smear situation. "Now we're glad he's gone. Hey, how're you doing Patty?"

"Oops," says Grohl. "We were between a rock and a hard place then. We were under his thumb. There are some songs he didn't even play on on that record."

More bothersome were pressures, both internal and external, to make a perfect-sounding record that would produce radio hits.

"The last album was the conventional rock recording method. Find a producer. Play the demos. Do pre-production. Go into the studio. Perfect everything. Go to mix. Make it perfect," says Grohl. "This record was: Try to build a studio in your basement. Try to make it as perfect as you can before you get tired of trying to make it perfect. Settle for the best you can do. There's no way that you could have a more relaxed recording environment. There's no label. There's no clock. We had no deadline. Once we finished our record, we said to labels. 'Here it is. Do you want it?' We had nothing left to lose. That's what you're getting on this album."

Grohl, who worries that his lyrics were too love letter-esque and emotionally obvious on the slick sounding The Colour And The Shape, revels in the imperfections of There Is Nothing Left To Lose.

"We made it a point to stay away from computers or ProTools," says Grohl. "It was important to me to make sure we got performances that were flawed in order to give them more personality. We spent time trying to get these songs right, but not just right. ProTools has become such a huge part of making an album and it seems to suck the life and soul out of songs especially on drums. It's awful.

"The legendary drummers - Keith Moon, John Bonham - were people who didn't have metronometime. You can hear in the songs that they didn't necessarily understand the arrangements as they were recording them.

Bonham was

famous for that. He would move into a chorus before it was there, and end up in the middle of it one bar later. It was great. Those performances are so memorable because they're human. They're not mechanical. Records sounded bigger because there were so many glitches, warts and imperfections that they were believable. Nowadays, radio has such a hard time with imperfection that we have to present the rock in its perfect form, and it just doesn't seem believable."

"The legendary drummers - Keith Moon, John Bonham - were people who didn't have metronometime. You can hear in the songs that they didn't necessarily understand the arrangements as they were recording them.

Bonham was

famous for that. He would move into a chorus before it was there, and end up in the middle of it one bar later. It was great. Those performances are so memorable because they're human. They're not mechanical. Records sounded bigger because there were so many glitches, warts and imperfections that they were believable. Nowadays, radio has such a hard time with imperfection that we have to present the rock in its perfect form, and it just doesn't seem believable."That's hardly an issue on Nothing Left To Lose, which neatly blends the strengths of both records: the raw immediacy of Grohl's one-man-band debut, and the catchiness and emotionality of Colour And The Shape. "Stacked Actors" rages viscerally against LA's platinum blondes. But "Aurora" is perfectly formed pop with heart-tugging lines like "I kinda died for you/You just kind of stood there." fora Name cmd Me First and the Gimme Gimmes guitarist Chris Shiflett. "Headwires" offers a psychedelic reminiscence of acid, while "Ain't It The Life" broods somberly, and the album-ending "M.I.A." rages against all things superficial, all the while sounding like a rehearsal captured on tape. The freedom to experiment came from the freedom of the suburbs.

"It had everything to do with getting away from the industry, building a studio on our own, and making an album on our own," says Grohl. "We wanted to prove to ourselves that we could do it, so that we could feel like what we are doing is real. There are times when it doesn't feel like it was real. And that had everything to do with moving back to Virginia."

Grohl gets up to grab a smoke, which seems like a good time to ask Hawkins and Mendel how they enjoyed the wonders of the Virginia suburbs.

"Virginia is as boring as you could ever fucking want it to be," says Hawkins. "We went out twice the whole time we were there because there wasn't much to do. It was comfortable there, but there wasn't anything happening."

"The area where Dave lives is just all strip malls and residential areas. It's all Chili's and Black Eyed Peas," adds Mendel. "It was weird. It didn't feel like we were making a record to me. It was so casual. The studio was a shambles. The equipment all worked fine, but it never really got put together. Those guys did so much work to get to the point where it was operational that making it look like a studio was secondary."

For Mendel, the key to the Nothing Much To Lose wasn't so much swapping LA for Alexandria as it was losing Stahl.

For Mendel, the key to the Nothing Much To Lose wasn't so much swapping LA for Alexandria as it was losing Stahl."Franz leaving the band was a really traumatic experience for me. I cried after it happened," he said. "But we all went through it together, and I feel like it made us closer. Right before we went in to record we had this traumatic bonding experience that gave us cohesion. It sounds dorky, but there was a lot of hugging going on before we made this record." Mendel's been through many of those group-affirmation hugs as the last remaining original Foo Fighter. First his pal and Sunny Day Real Estate bandmate William Goldsmith cracked under the pressure of playing drums in Dave Grohl's band. Then Pat Smear took his brightly hued hair and bad attitude and went home, only to be replaced by the since-departed Stahl. Stahl's replacement, just in time for tour, is No Use for a Name and Me First and the Gimme Gimmes guitarist Chris Shiflett.

"With other bands, there's drug addiction and rehab. We just have people go," says Mendel.

"This band didn't have the luxury of not growing up in the public eye," Hawkins explains. "This band has been totally growing up in public, and growing up, and growing up."

"I don't know if people realize that when they make comments like, 'Why can't you guys keep any members?' It just doesn't come across people's minds," adds Mendel.

"Let it be known that it's not Dave putting that pressure on anyone." says Hawkins. "It's the kind of pressure anybody puts on themselves when they're up against something that's going to be hard. We all are lucky as hell to be in this band."

Grohl returns, curious about what's been discussed in his absence.

"Oh, you know," says Hawkins, in a teasing, singsong voice. "That Dave, he sure can't keep a band together."

"Well," cracks Grohl, "neither could Prince. He lost a band member every single."

"That's because he was probably a dick," Hawkins retorts. Grohl scratches his chin with a mock-ponderous pose. "Hmmm."

Perhaps the only thing Grohl's less concerned about than public perception that he can't control is the reception the latest Foo Fighters album will receive from modern rock radio programmers whose jobs, ultimately, were created by the Nirvana revolution.

Perhaps the only thing Grohl's less concerned about than public perception that he can't control is the reception the latest Foo Fighters album will receive from modern rock radio programmers whose jobs, ultimately, were created by the Nirvana revolution."If we were concerned about that kind of thing we probably would have made a slicker record, with computers, machines and two turntables and a microphone," Grohl says. "But we're not, so we didn't. I think what's going on, and one of the reasons why we don't necessarily fit into a lot of what's happening on the radio, is there's an absence of melody. It's more about the sounds than the songs. It's more about the dynamics than the arrangements. It's more about how huge a song can get rather than if it can go from point a to point b.

"A lot of songs nowadays are just built on super-basic caveman dynamics. Quiet. Creepy. Grrr! Loud. Quiet. Creepy. Grrr! Loud. Some of it's interesting, but it doesn't seem to challenge anything. No one seems to be challenging the listener anymore."

Grohl doesn't blame lazy programmers, novelty one-hit wonders or lame Nirvana rip-offs, as much as he does those artists who should know better. The problem, he suggests, springs from alt-rockers who have betrayed the roots of the '80s DIY scene that spawned '90s alt-rock by believing that they can become cartoonish rock stars capable of being rock-and-roll saviors. He's well aware that the Foo Fighters anti-California glamour album will be compared to Hole's Celebrity Skin, the in-love-with-it-all take on falling in love with Malibu and Fleetwood Mac that Cobain's widow Courtney Love released last year. "Yeah," Grohl agrees, then seems to address Love without ever mentioning her by name. "Things have gotten so desperate that all these artists have claimed that they're coming to save rock 'n' roll. That the world needs rock stars to save rock 'n' roll. When in reality, the world needs music to save rock 'n' roll. Everyone was kind of missing the point." "What these people were saying is, 'Kids need a super-hero fucking rock star to look up to and worship like a fucking cartoon character. because that's what rock is all about.' Sure in the '70s you had rock stars who were cartoon characters. Steven Tyler's lips, Mick Jagger's lips, Robert Plant's crotch. But they had music to back it up. "I'm surprised that a lot of the people who seem to have come from maybe the some punk rock background somewhere got it blurred. The rock star was more important than the music. The image was more important than the

music. The sound was more important than the song. I don't want to come off sounding like a songwriting genius, because I'm not. All I do is make songs we're capable of making. But all our focus is on that — not on anything else. People don't know what to believe in because they don't think anything's believable."

Indeed, what Grohl's identified is all part of the post-Nirvana fallout, part of the old boss/new boss cultural shift that put a modern rock station in every town but ensured that they'd play nothing but Third Eye Blind and the Goo Goo Dolls, and that allowed millions to hear Johnny Marr's scintillating guitar riff that opens the Smiths' "How Soon Is Now?" only as a Nissan ad.

Indeed, what Grohl's identified is all part of the post-Nirvana fallout, part of the old boss/new boss cultural shift that put a modern rock station in every town but ensured that they'd play nothing but Third Eye Blind and the Goo Goo Dolls, and that allowed millions to hear Johnny Marr's scintillating guitar riff that opens the Smiths' "How Soon Is Now?" only as a Nissan ad. If Nirvana and Cobain kicked down that door, Cobain didn't like what he saw inside. His death presaged the mainstreaming of alternative but left the new youth culture Nirvana created leaderless, and with an authenticity void exceedingly vulnerable to being hijacked by whining one-hit dullards or superstar hype machines like Love. Would these issues exist if Cobain had lived to provide a different example?

"If he were around? I don't know. That's a weird question to answer," Grohl says. "But I still feel the same, if not angrier. I mean, when we were young, in the mid-'80s, we were singing and screaming about our hate for superficial things, right? I'm angrier now, probably more so than I was then. I don't think I could ever do the rock star thing. It would just be too strange. It seems like that movie Sybil. How on earth could you walk on stage and be someone else and not lose your fucking mind? How could you look in the mirror and see someone else?"

Now, looking at himself as a single suburbanite, with his acre-and-a-half Alexandria home, Grohl looks and the mirror and, for once, likes what he sees. He's a songwriter secure enough with himself to believe in his experiments, whose insecurities keep him humble and unassuming, and who draws out his thoughtful, introspective side simply without thinking about it too much.

"I think with the last record we were scared to do something like this because we still felt like we were supposed to be a hardcore band or a punk-rock band, or loud and crazy. At least I did. I wasn't comfortable enough as a vocalist or guitarist to dive into that yet," Grohl says. "One of the things about this record that I hear is we're comfortable doing those things. Before they might have sounded forced. They may have sounded like a garage band or a punk-rock band trying to write ballads and trying to pull them off.

"Now, it's just, 'Fuck it.' I don't give a shit. I know we can do it. The three of us can do fucking anything we want. We really can. We can do fucking Yes covers, or we can do an Angry Samoans cover. And that's what's wrong with rock 'n' roll. No one has that range anymore. I really believe we can make any kind of record that we want. We could go out and make a drum 'n' bass record. We could go make a metal record. For sure we could make a metal record! We could make a record way poppier than this if we wanted to. It's up to us to decide which direction we want to go in."

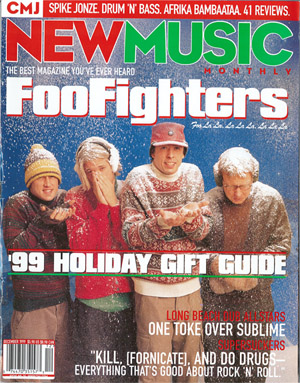

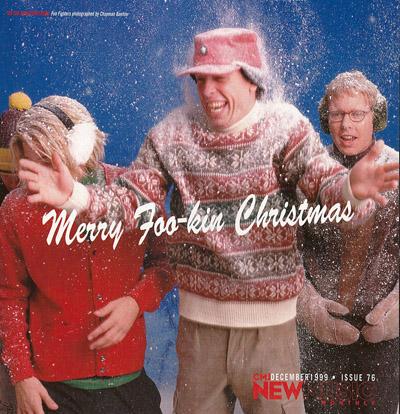

Words: David Daley Pics: Chapman Baehler